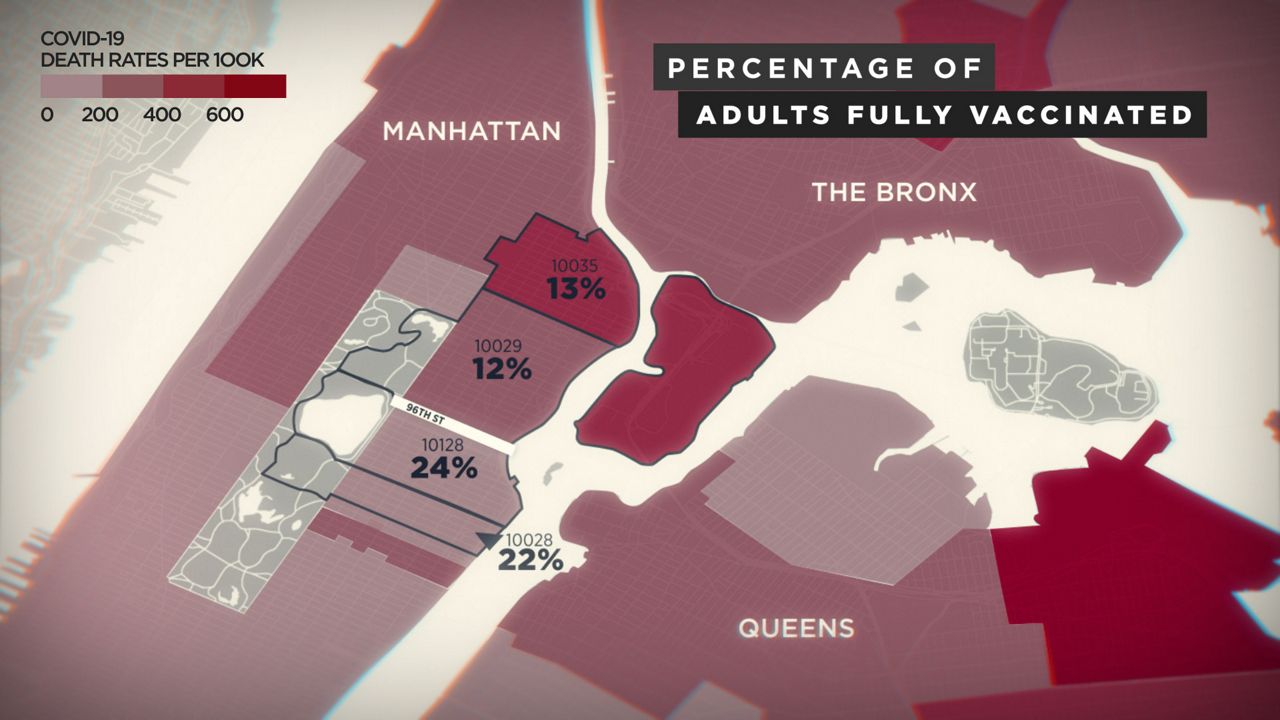

MANHATTAN — Below 96th Street is the Upper East Side, one of the wealthiest areas in the city. Above it is East Harlem, the center of Hispanic culture known as El Barrio.

Below 96th Street, more than a quarter of all adults have been fully vaccinated for COVID-19.

Above it, about 13% are fully immunized — and there are fewer than half as many sites at which to get the vaccine, including sites at local pharmacies.

The street, long one of New York City’s most drastic geographical divides for health and access to medical care, is now a dividing line for vaccine access and for the impact of COVID-19.

In East Harlem, COVID death rates for the pandemic are more than triple that of the Upper East Side, according to city data. One of its ZIP codes, 10035, has the highest death rate in the borough.

What You Need To Know

- East Harlem is right above the Upper East Side, but has faced dramatically worse death and infection rates during the pandemic

- Three months into the vaccination effort, its rate of vaccinated adult is about half that of the Upper East Side, despite being on par with city-wide averages

- The city had planned to open a vaccine hub at a marketplace in East Harlem, but after the plan feel through no other site has been announced

- A new federal program sending vaccines directly to community health centers will help give one local clinic capacity to vaccinate East Harlem residents

The deep impact there from the pandemic led Mayor Bill de Blasio to put East Harlem on a list of ZIP codes that would receive special attention during the vaccine rollout. In January, his administration said that the city would create a major vaccination hub in the neighborhood that would cater to residents who tend to prefer medical treatment in a neighborhood where they feel safe and understood.

Yet more than a month and a half after initial plans for a hub at a neighborhood marketplace fell through, the city has not presented any new plans for such a hub in the area.

A spokesperson for the mayor said in an email that the administration is “exploring the options of other sites.”

The spokesperson noted that vaccination rates in East Harlem are above the city-wide average, and that the city has run multiple pop-up sites in public housing developments.

“We’ve been overwhelmingly clear that the current disparities in vaccination rates by neighborhoods across the city are unacceptable,” the spokesperson said.

The lack of vaccine access has left community clinics who are administering vaccines scrambling to increase their capacity, and has frustrated residents who are not able to navigate vaccine scheduling websites. Some say they cannot leave the area to get vaccinated for fear of having to overcome a language barrier or because they cannot afford the time or expense.

Domingo Alvarez, 53, who is disabled and has diabetes and heart issues, said his daughter called every day to try and get him an appointment after he became eligible last month due to his preexisting conditions but was unsuccessful.

“She tried to get me an appointment every way she could,” he said. “I wanted to get it, but I couldn’t find a place.”

He eventually received a vaccine through Union Settlement, an East Harlem services provider, after they called him and set up an appointment through their senior center.

“Why were we not prioritized?” said City Council Member Diana Ayala, who represents East Harlem and parts of the South Bronx. “Stop using our ZIP code as a focal point of conversation if we’re not gonna benefit from being on this list of most impacted areas.”

Now, a new federal program that will provide vaccine doses directly to hundreds of New York community health centers is set to give a significant boost to vaccination efforts in East Harlem. Sen. Chuck Schumer included the $32 billion program in the December COVID-19 relief bill.

The Boriken Neighborhood Health Center, a clinic on East 123rd Street, will be able to order vaccines through the program starting Thursday, according to Dr. Adam Aponte, Boriken’s chief medical officer. It’s unclear when the doses will start arriving and how many they will be able to receive each week, Aponte said.

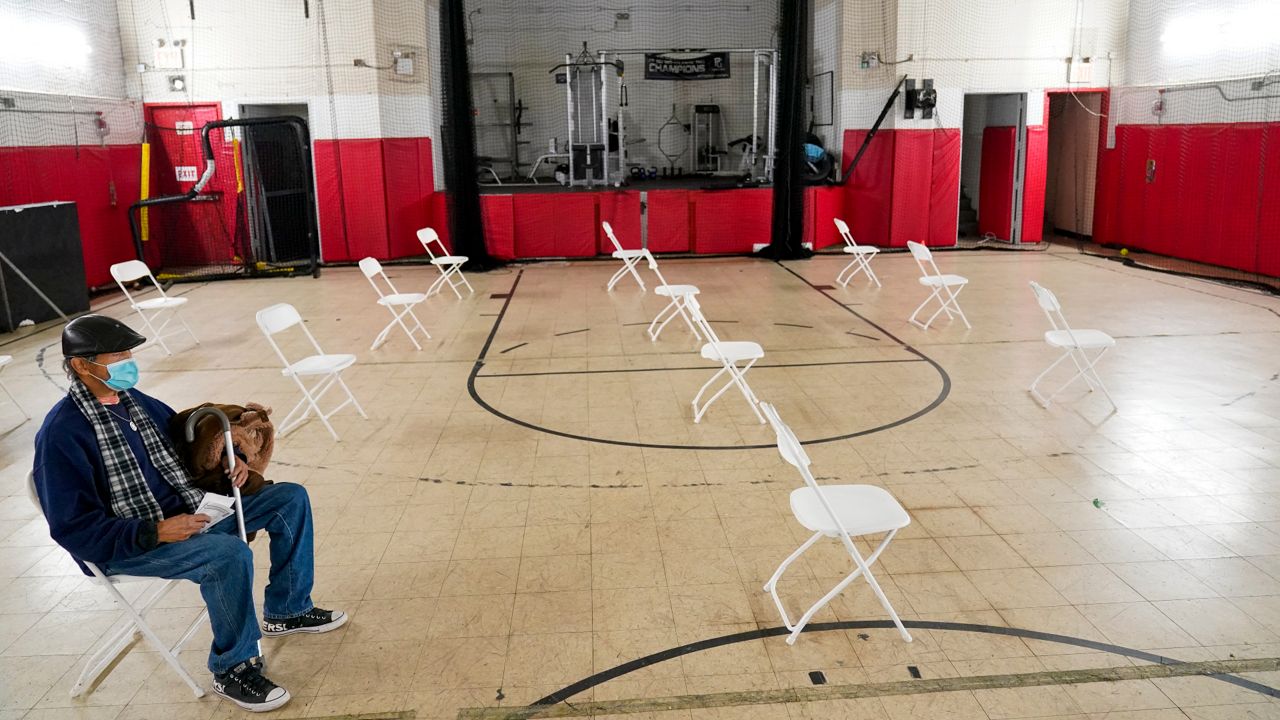

Aponte said the clinic has been working to find a venue where they can vaccinate more than the 40 to 50 people their clinic can handle on weekdays.

He thinks he’s found the spot: the gymnasium of Taino Towers, four 35-story public housing towers on the block between 2nd and 3rd Avenues just south of the Boriken clinic.

The space, he says, will allow them to vaccinate up to 150 people a day. He hopes to start vaccinations there within two weeks.

It’s far fewer vaccines than some of the city’s major vaccine hubs, like the Javits Center and Yankee Stadium, which have the capacity to administer thousands of doses a day.

But, Aponte says, at least it will be located in El Barrio.

“I have members of our community who are 70-, 80-, 90-year-old women, and they've lived in our community all their lives, and they're not gonna stand in line at the Javits Center for three hours,” he said.

'An accident of history'

East 96th Street has long been a cultural, health and socioeconomic divide in Manhattan, according to David Rosner, a professor of public health and social history at Columbia University.

“96th Street is a kind of an accident of history,” he said.

In the late 19th century, it was the natural upper border for the collection of mansions built near the park by the city’s wealthiest families, such as the Carnegies, since on the northern side of the street, the island went steeply downhill.

The expansion of the subway above 96th Street, completed in 1918, drew Italian and Jewish immigrants out of the pressure cooker of the Lower East Side. In the 1930s, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who had represented East Harlem in Congress, helped build large public housing developments for his former poor and working class constituents.

The neighborhood stayed working class, but through the next decades changed over to being predominantly Black and Latino, just as the city began a financial decline and disinvested from poor and working class neighborhoods.

“They were what we call essential workers today,” Rosner said. “But they were seen then as poor people who were trying to take advantage of our tax dollars.”

Now, health risks are drastically higher for East Harlem residents than for those in the Upper East Side, including for diabetes, heart problems and other health issues that make a person more likely to die from COVID-19.

A 2018 estimate of census tracts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that double the number of Upper East Side residents over 65 years old reported having access to preventative services compared with those in East Harlem.

“It should be no surprise at all that some of the same disparities would exist when it comes to getting the vaccine, between the Upper East Side and East Harlem,” said Chris Palmedo, a professor of marketing at CUNY’s School of Public Health. “It’s a sad juxtaposition, because they're so close to each other, and one is one of the highest cluster of socioeconomic outcomes in the country, and the other is improvised.”

'Warmth and welcome'

Ayala said she has been frustrated that, given the historical and recent health disparities that have affected East Harlem, that the area still does not have a city-backed mass vaccine site. Her office, she said, has been helping residents who have trouble using scheduling websites or vaccine hotlines to make appointments for shots, often getting them appointments in other boroughs.

Ayala she has been trying for three weeks to get herself a shot in the neighborhood, where she lives, with no success.

“I refuse to leave the community to do that,” she said. “I don’t think it's fair for the people who live here to be subjected to that.”

The city had initially planned to place a vaccine site at La Marqueta, a marketplace and event space underneath the elevated subway line on Park Avenue. But the city backed away from that plan in early February. A spokesperson for the mayor said that one of the issues is that there were insufficient electrical outlets at the site.

Ayala said she received little communication from the mayor’s office over the site, and said she did not understand the wall socket issue, given that the market hosted a night market with hundreds of vendors — and plenty of lights — in the summer of 2019.

Ayala said she provided a list of possible alternative sites to the mayor’s office in early February, including Taino Towers’ gymnasium, but received no response.

A spokesperson for the mayor said that the administration continues to do “on the ground, census-style outreach” to community leaders to help residents make appointments through community-based organizations, and prioritizes frontline city workers in the neighborhood to help them reserve appointments.

Aponte said he is reaching out to medical student groups and the city to help staff the upcoming effort at Taino Towers. Last night, he said, he had an initial meeting with members of Mount Sinai medical school’s Latinx and Black student groups.

They are also relying on a recent $50,000 grant from the Hispanic Federation to boost their staffing.

For residents of El Barrio, Aponte said, who put a high premium on trust and comfort when seeking medical treatment, it is crucial to have a vaccine site within the neighborhood that is staffed by familiar faces.

“It’s not this cold, ‘Have a seat here, fill out this form, we’ll get to you when we get to you,’” Aponte said of his clinic’s approach to seeing patients. “It’s, ‘Hola doña, how is your family, it’s good to see you.’ That type of warmth and that type of welcome goes a long way for people in our community.”