A row of homes in Central Brooklyn may not look like much, but it holds a significant place in the city’s history. They are what remains of Weeksville.

“Weeksville was the second largest free Black community in the United States,” Prithi Kanakamedala said. “It was secluded, in that it was just outside that city border. It was an intentional free Black community, so I always think of freedom seekers as coming to Brooklyn, knowing that Weeksville existed [in] 1838, just 11 years after slavery finishes in New York State.”

What You Need To Know

- Weeksville, in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, was the second largest free Black community in the United States

- Freedom seekers coming from the south to Brooklyn were looking for economic opportunity, according to Prithi Kanakamedala, a professor of history at CUNY and the author of "Brooklynites"

- The community was founded by James Weeks, a freed Black man from Virginia who purchased a plot of farmland; at one point in the 1850s, there were more than 500 residents

- Weeksville had its own institutions, churches, schools, baseball team, and newspaper called “The Freedman’s Torchlight," so the community created a safe space for freed Blacks, according to Raymond Codrington, president and CEO of Weeksville Heritage Center

Kanakamedala is a professor of history at CUNY, and the author of “Brooklynites,” a book about the borough’s free Black communities.

“A lot of those freedom seekers coming from the south to Brooklyn, they were looking for economic opportunity. They were looking at a start of a new life,” Kanakamedala said.

The community was founded by James Weeks, a freed Black man from Virginia who purchased a plot of farmland. The town expanded with the help of African-American land investors and political activists. At one point in the 1850s, there were more than 500 residents.

“At that time if you had land, property worth above $250 and were Black, you could essentially gain the right to citizenship, and vote,” Raymond Codrington, president and CEO of Weeksville Heritage Center, said. “Weeksville had its own institutions, churches, schools, home for the aged, an orphanage, a baseball team, and even had a newspaper called ‘The Freedman’s Torchlight’ so it was really an act of self-determination, and really a way to create a safe space for freed Blacks."

Today, the four historic homes that remain are known as the Hunterfly Road Houses. Landmarked in 1970, they are located in Crown Heights. The property is operated by the Weeksville Heritage Center, which is working to raise awareness of its historical significance.

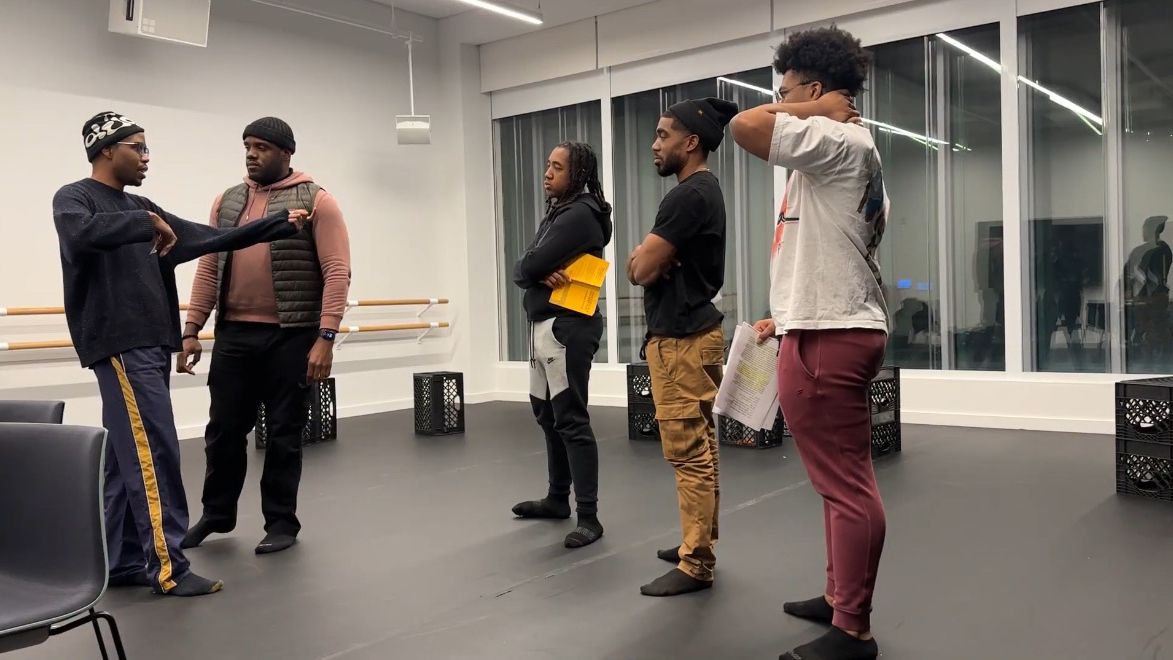

“People don’t expect a free Black community with houses like this that have been preserved, that are landmarked, to be in one’s midst, so it’s really having history under one’s nose but really not realizing it,” Codrington said. “And we are attempting, in every way that we can, to get the word out about the kind of programs that we do, have people take house tours to learn more about Weeksville’s history, to engage in public programs. One of the things that’s very interesting about Weeksville is that the spirit and the energy of those people that founded the community is still here.”

To learn more about Weeksville, including available programming and exhibitions, check here.