It’s not difficult to name inventions that changed weather forecasting: thermometers, barometers, satellites… the list goes on. But some inventions’ origins, or their effects on weather forecasting, may surprise you.

“What hath God wrought?”

Samuel F. B. Morse sent that very first telegraph message on May 24, 1844. The implications were enormous. Before this moment, it might take days or weeks for a message to reach its destination. Suddenly, information could be exchanged instantly, and that included weather information.

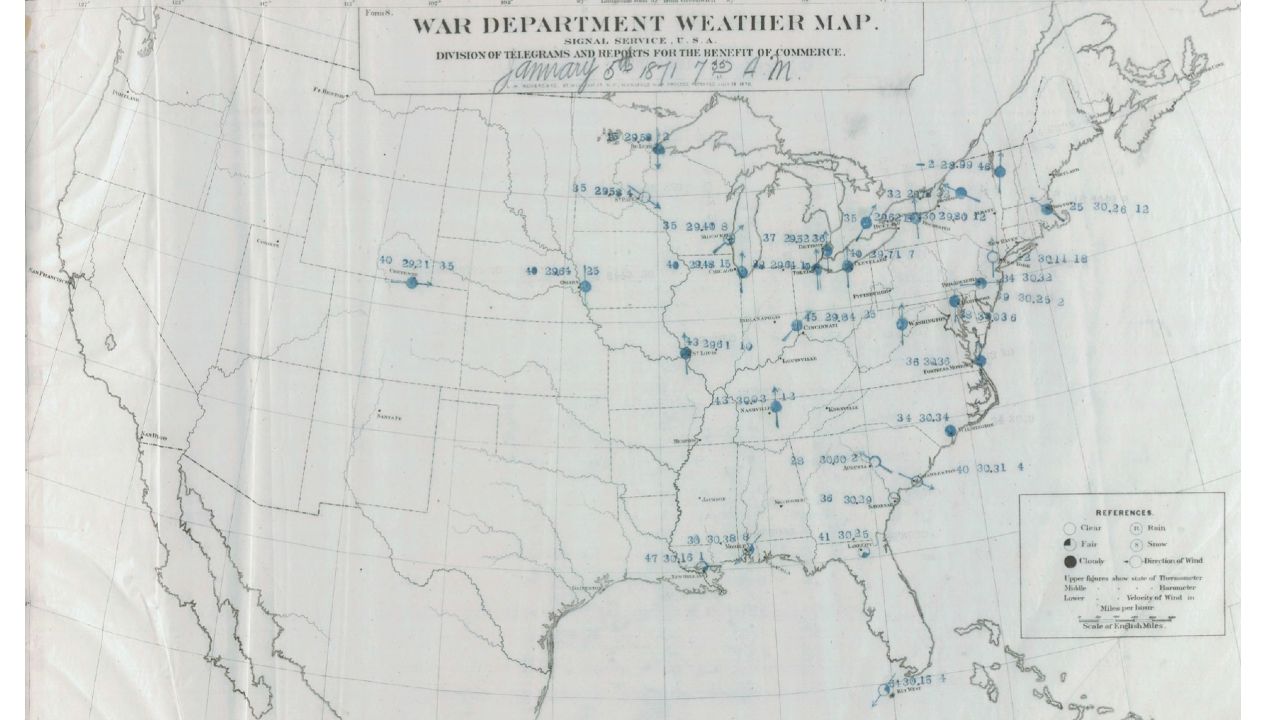

The Smithsonian established a network of weather observers around the country who regularly telegraphed their reports of clouds, precipitation, temperature, and wind. Those reports went on a large map publicly displayed at the Smithsonian – an early version of the weather maps we’re so used to today.

Scientists studying the data knew it could hold keys to unlocking some of weather’s mysteries. They could follow a weather system’s progress, alerting authorities to impending trouble using the same telegraph system.

This rudimentary but valuable system helped lead to the federal government creating its own weather bureau in 1870. While we don’t use telegraphs to send and receive weather data anymore, the telegraph set the stage for what we have today.

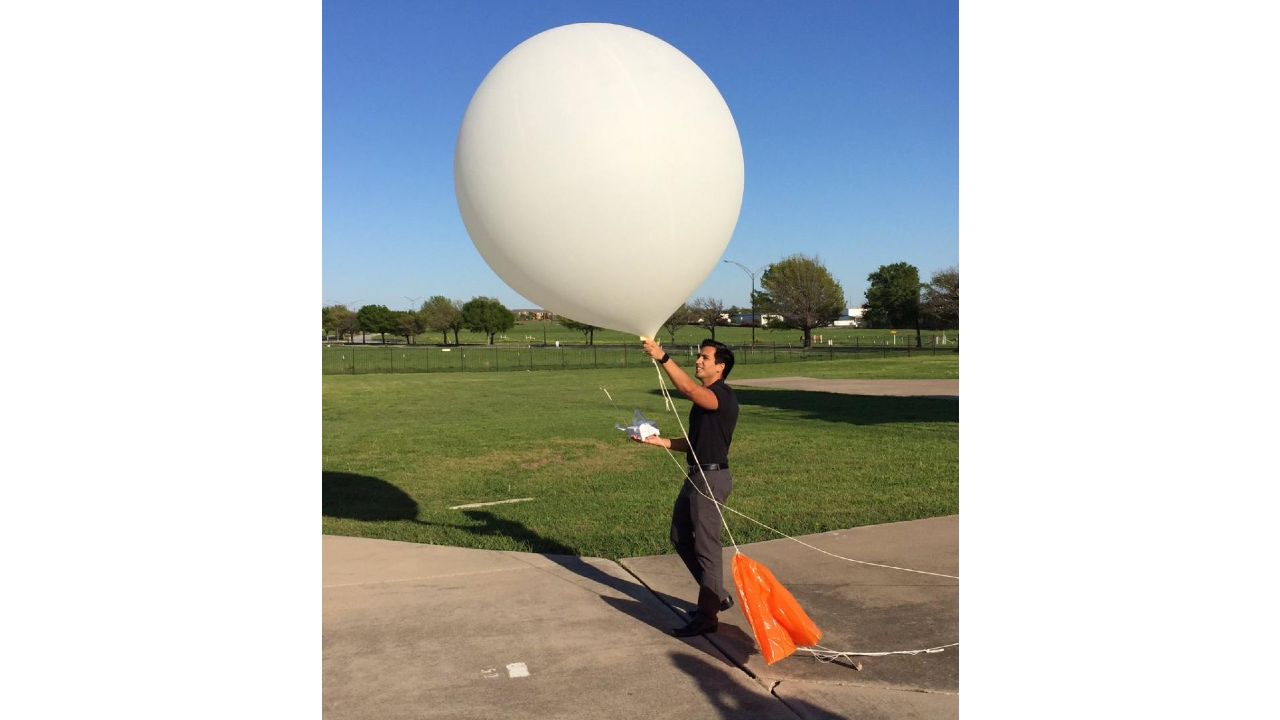

Most people care only about the weather on the ground, but conditions miles above our heads are just as important. Weather balloons measure temperature, moisture, and wind throughout the atmosphere.

Just days after the first manned hot air balloon flight, Jacques Charles and Nicolas Robert performed the first manned hydrogen balloon flight in France on December 1, 1783. They took a barometer and thermometer with them, measuring air pressure and temperature on their way to nearly 10,000 feet.

Of course, it soon became obvious that it would be impractical to launch a big balloon carrying a person to take multiple measurements. French meteorologist Léon Teisserenc de Bort launched hundreds of unmanned balloons around the turn of the 20th century. Today, meteorologists send up balloons twice a day from hundreds of locations around the globe.

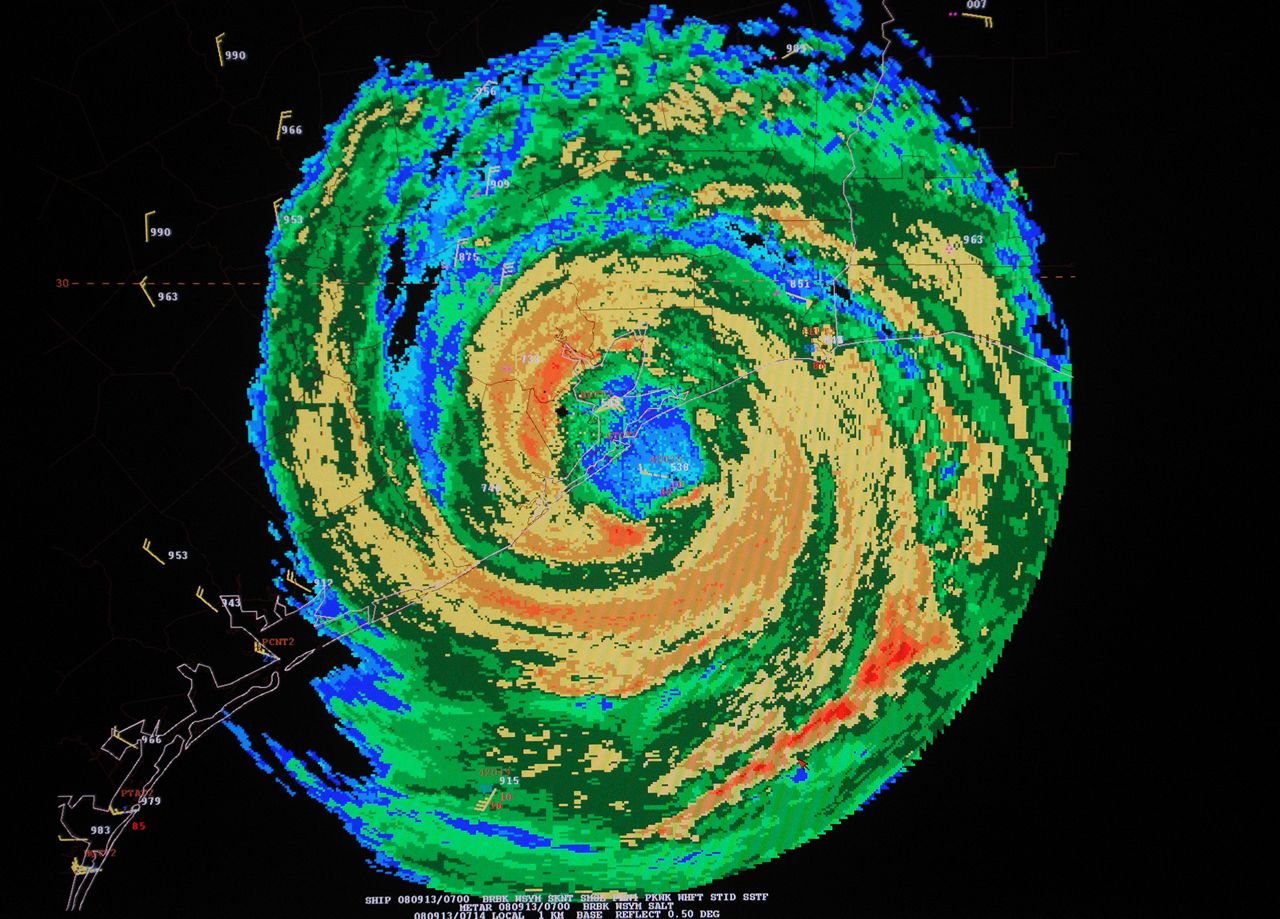

Radar, which is actually an acronym for “radio detection and ranging,” is often used to detect precipitation. But it wasn’t developed for that purpose; in fact, that was sometimes an undesirable side-effect in its early days.

Early on, radar’s main use was in military operations. When a radar transmitter’s energy reflects off ships or airplanes, some of that energy comes back, helping to target enemy positions.

Precipitation also reflects that energy, though. Targets would appear where there weren’t planes, or pilots could use precipitation to help mask their presence. Of course, knowing the position of rain or snow could give an advantage, too, in the form of a short-term forecast.

For various technological reasons, military radars didn’t cut it when it came to meteorological needs. Researchers set about developing radars specifically for weather use, and the Weather Bureau’s (now the National Weather Service) first radar network began in 1959.

Today, weather radar is an invaluable tool for detecting everything from snow to tornado debris. The next generation of weather radar, which also has military origins, is able to scan the entire sky in less than a minute.

The Wright Brothers made their first successful flight in 1903. Forty years later, a U.S. Air Force pilot intentionally flew into a hurricane off the Texas coast. Hurricane Hunters are a crucial part of gathering data on tropical storms and hurricanes.

But this isn’t about them. It’s about devices attached to aircraft – which, just like weather balloons, start near the ground and go up in the atmosphere, able to take samples of the weather all along the way.

More than 40 airlines around the world participate, collecting many thousands of “profiles” of the atmosphere every week. That information feeds into computer weather models, supplementing the data from weather balloons and satellites, with the aim of producing more accurate forecasts.

Fewer aircraft flying during COVID-19 means fewer observations, which potentially has an effect on weather forecast models.

Military forces around the world have used unmanned aircraft for decades, but one look at an electronics store shows how popular they’ve become for hobbyists. It turns out, they’re also useful for weather observation and research.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and some universities have begun experimenting with using drones to collect the same information as weather balloons and survey disaster damage. Hurricane Hunters have sent drones to the lowest parts of a hurricane where it’s far too dangerous to fly a plane.

Weather forecasting would be impossible without inventions created for specific purposes such as measuring temperature. But the clever minds who can see uses for seemingly unrelated inventions help drive our understanding of meteorology further than we otherwise could have.