In day-to-day life, there are some things we expect to happen without a thought. One is that the lights turn on when you flip a switch (or, in today’s world, tell your digital voice assistant to do so). With so many extreme weather events happening across the nation affecting the power grid, it now becomes harder to imagine a future scenario where the lights will work all the time without fail.

Take Hurricane Isaias, for example. More than two million electricity customers across the Northeast lost power. Some were in the dark for up to one week. With high winds and more than 15 feet of storm surge, Hurricane Laura left 400,000 customers in the dark even miles inland from the Louisiana coast. The utility companies in California started rolling blackouts to maintain the grid’s integrity and prevent wildfires last month, as record heat arrived in the state.

Peer-reviewed research has been published on the matter of power outages, with parts of New Jersey seeing a week-long blackout in 2019 due to a line of summertime thunderstorms.

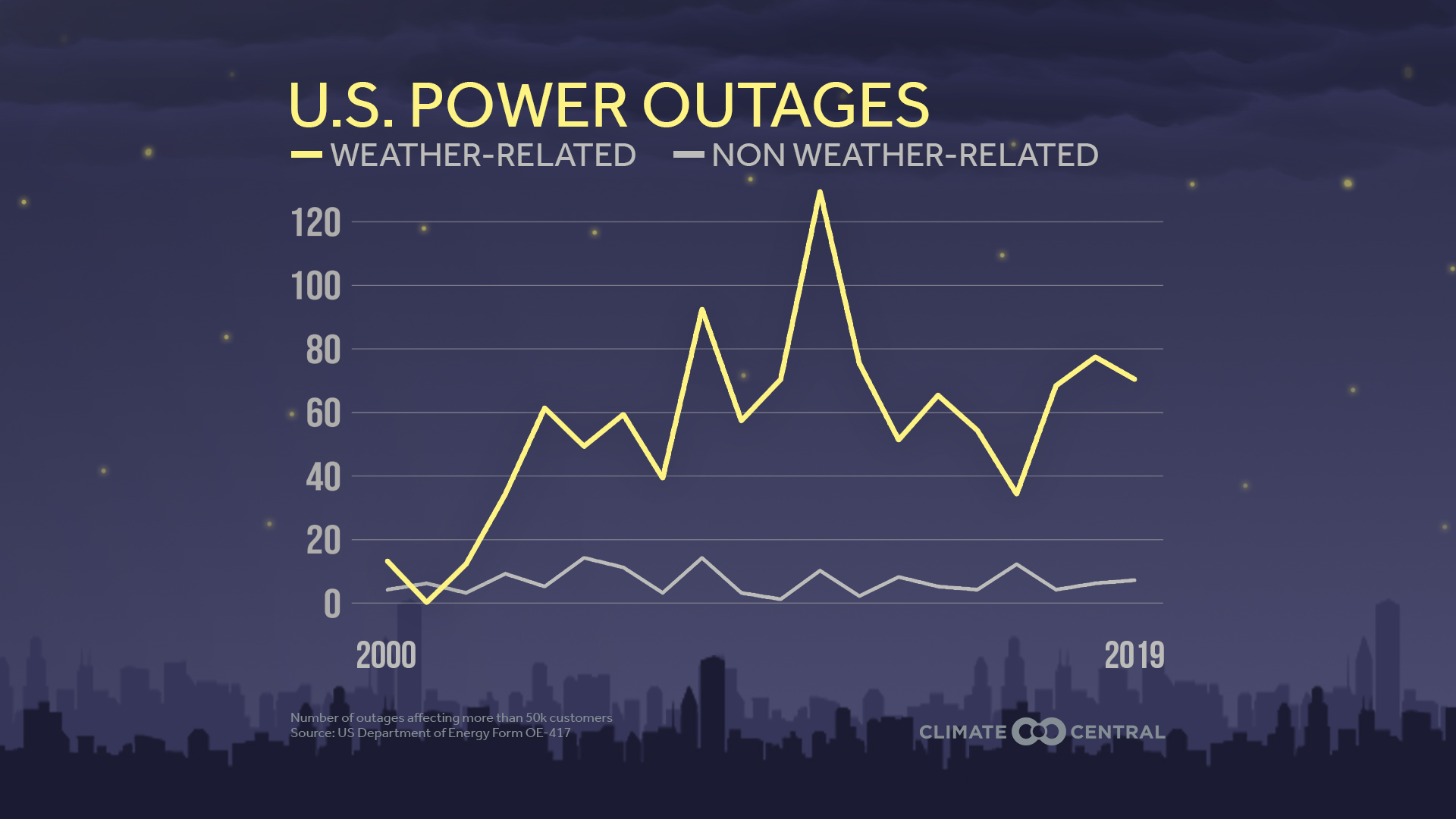

We know that extreme weather disasters are increasing in frequency, according to the National Climate Assessment. This trend has continued for the last 20 years.

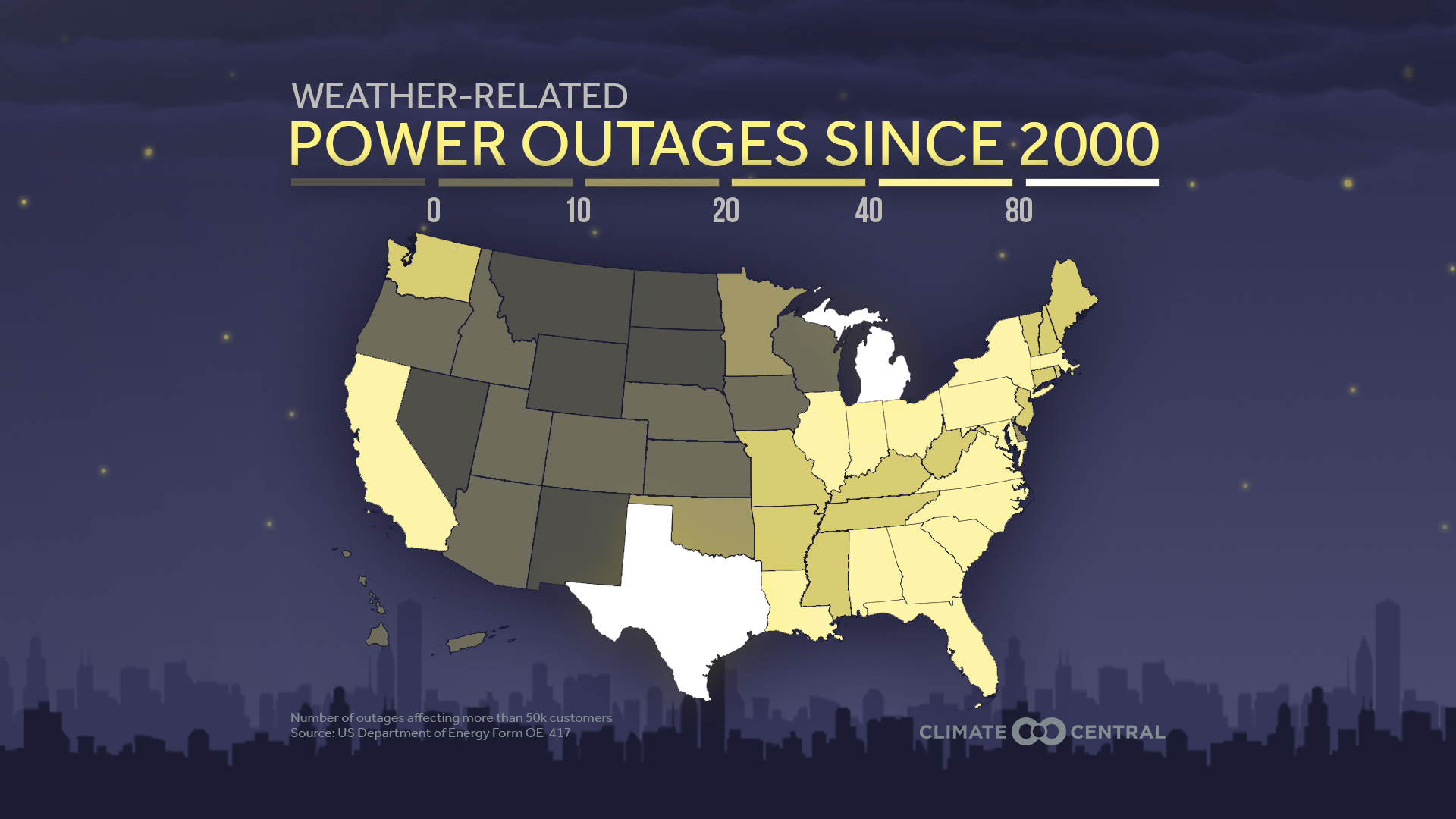

In data collected by Climate Central, an independent science and news organization of leading scientists and journalists researching and reporting the facts about our changing climate and its impact on the public, the data show a 67 percent increase nationwide in major power outages (those affecting more than 50,000 customers) in the current decade compared to the previous decade.

Regionally, the northeast U.S. had a 159 percent increase in weather related outages decade over decade, since 2000.

Since most of the transmission and distribution network is above ground, the wires, poles and transformers that deliver power are particularly vulnerable to severe weather. But do buried lines offer an advantage? Not in Texas, where Hurricane Harvey cut power to Houston’s underground grid when the storm flooded the city with feet of rainwater.

During electrical blackouts, some turn to portable or permanent backup generators that run on a variety of fuels. Those fuels are refined from oil that are sometimes extracted from rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. When a hurricane, like Delta, hits that energy production area, those rigs and refineries are shut down and taken offline for safety. While the gas and oil still flow to where it’s needed, the prices become higher as supply is lower.

Some resiliency solutions are microgrids that offer round-the-clock self sufficiency. Microgrids are widely used in the US at hospital complexes where uninterrupted power is a matter of life or death.

When these microgrids are fueled by renewables, they offer a sustainable source of power for decades to come.

Solar and battery energy storage is becoming a more economically advantageous option for lower-income areas due to solar and wind energy now being cheaper than coal energy. Puerto Rico plans to install the nation’s largest solar and battery storage system after Hurricane Maria cut power to most of the island in 2017.

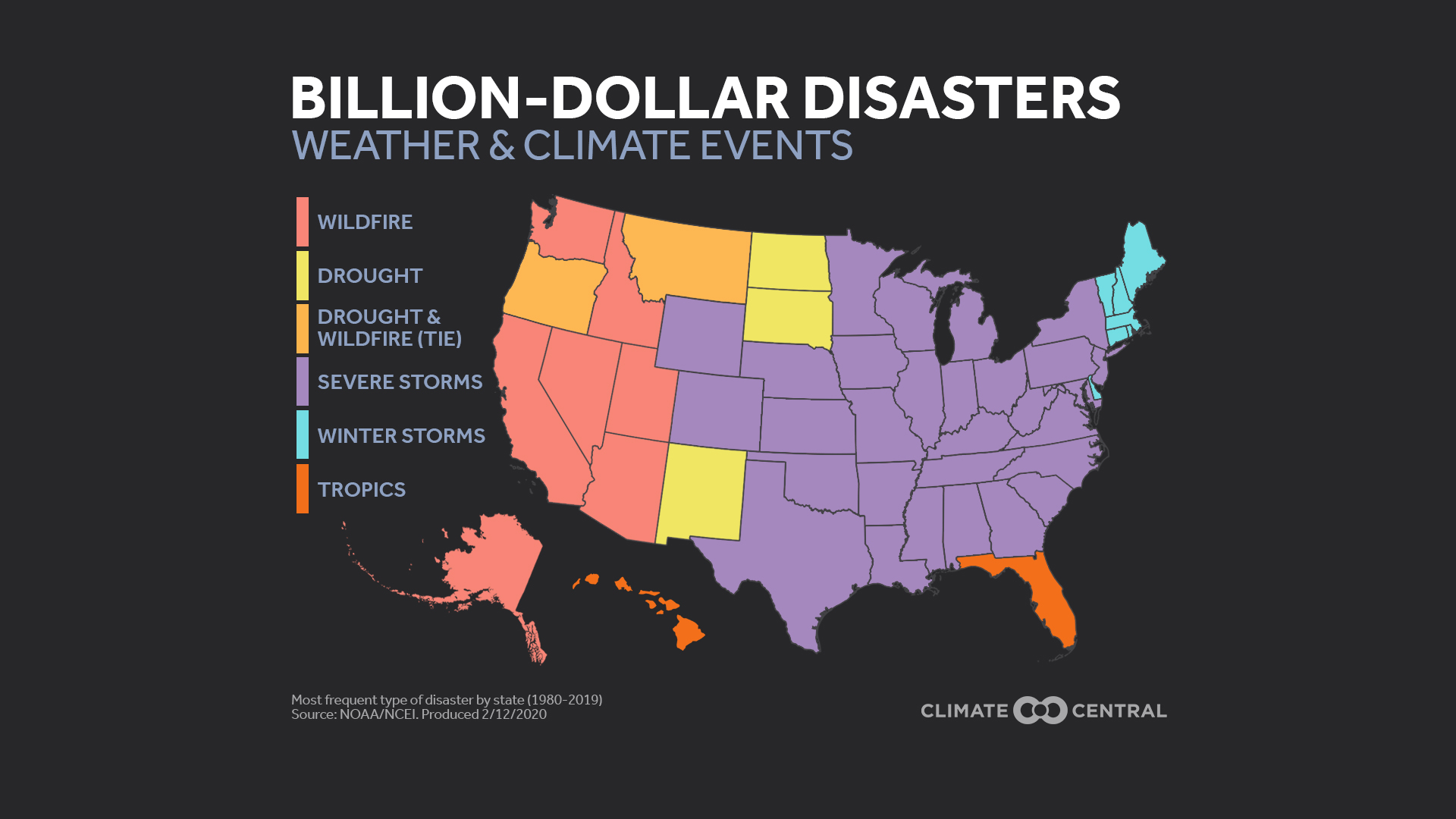

Making the grid more robust with smart technologies can help keep the lights on, including improved weather modeling to deploy utility crews for faster repair. But with severe storms representing most of the billion-dollar disasters of climate and weather events since 1980 (NCEI/NOAA) we’ll have to be individually be more prepared for how to cope when the lights go out.