Congress is discussing changes to the immigration system in exchange for providing money to Ukraine in its fight against Russia and Israel for the war with Hamas.

President Joe Biden has said he is willing to make “significant compromises on the border” to meet Republican demands that the assistance be tied to an overhaul of U.S border policy.

Republicans say the record numbers of migrants crossing the southern border pose a security threat because authorities cannot adequately screen all the migrants and that those who enter the United States are straining the country’s resources. GOP lawmakers also say they cannot justify to their constituents sending billions of dollars to other countries, even in a time of war, while failing to address the border at home.

But many immigration advocates, including some Democrats, say some of the changes being proposed would gut protections for people who desperately need help and would not really ease the chaos at the border.

Much of the negotiating is taking place in private, but some of the issues under discussion are known: asylum standards, humanitarian parole and fast-track deportation authority, among others.

A look at what they are and what might happen if there are changes:

HUMANITARIAN PAROLE

Using humanitarian parole, the U.S. government can let people into the country by essentially bypassing the regular immigration process. This power is supposed to be used on a case-by-case basis for “urgent humanitarian reasons” or “significant public benefit." Migrants are usually admitted for a pre-determined period and there’s no path toward U.S. citizenship.

Over the years, administrations, both Democratic and Republican, have used humanitarian parole to admit people into the U.S. and help groups of people from all over the world. It’s been used to admit people from Hungary in the 1950s, from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos during the latter half of the 1970s, and Iraqi Kurds who had worked with the U.S. in the mid-1990s, according to research by the Cato Institute.

Under Biden, the U.S. has relied heavily on humanitarian parole. The U.S. airlifted nearly 80,000 Afghans from Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, and brought them to the U.S. after the Taliban takeover. The U.S. has admitted tens of thousands of Ukrainians who fled after the Russian invasion.

In January the Democratic administration announced a plan to admit 30,000 people a month from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela via humanitarian parole, provided those migrants had a financial sponsor and flew to the U.S. instead of going to the U.S.-Mexico border for entry.

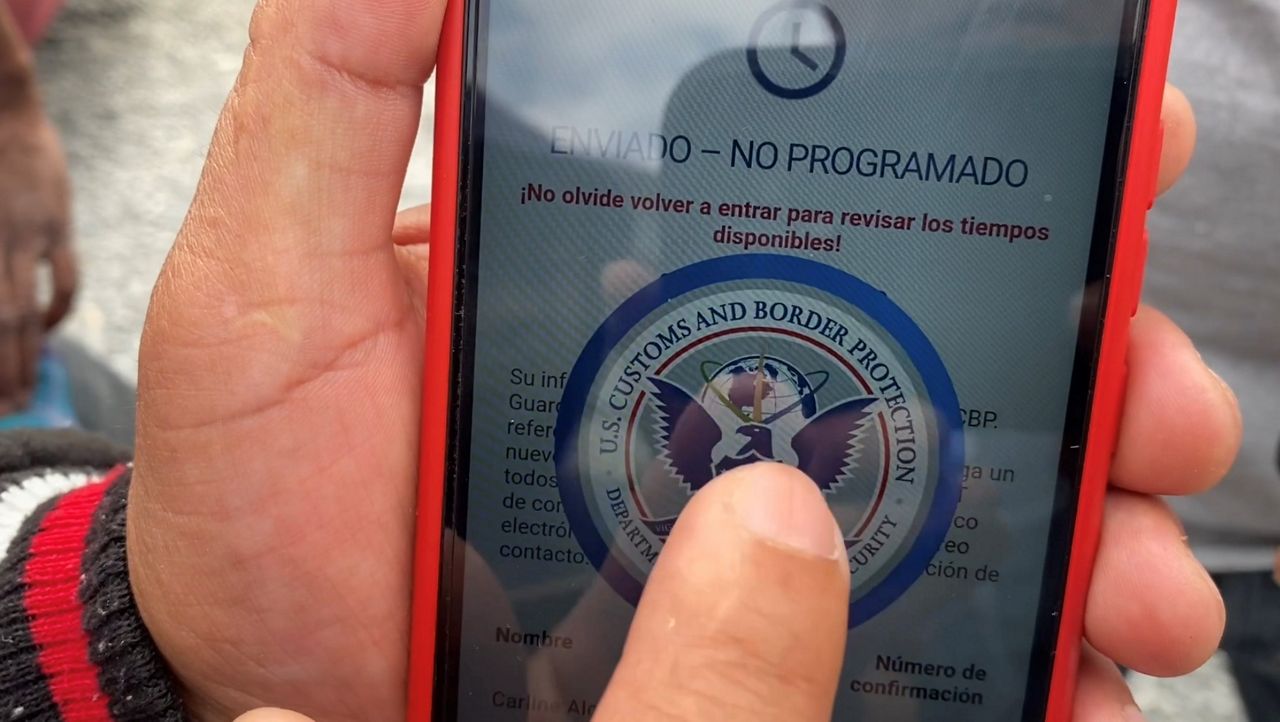

The latest U.S. government figures show that nearly 270,000 people had been admitted into the country through October under that program. Separately, 324,000 people have gotten appointments through a mobile app called CBP One that is used to grant parole to people at land crossings with Mexico.

Republicans have described the programs as essentially an end run around Congress by letting in large numbers of people who otherwise would have no path to be admitted. Texas sued the administration to stop the program aimed at Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans.

WHAT MIGHT CHANGE WITH ASYLUM?

Asylum is a type of protection that allows a migrant to stay in the U..S. and have a path to American citizenship. To qualify for asylum, someone has to demonstrate fear of persecution back home due to a fairly specific set of criteria: race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinions. Asylum-seekers must be on U.S. soil when they ask for this protection.

They generally go through an initial screening called a credible fear interview. If they are determined to have a chance of getting asylum, they are allowed to stay in the U.S. to pursue their case in immigration court. That process can take years. In the meantime, asylum-seekers can start to work, get married, have children and create a life.

Critics say the problem is that most people do not end up getting asylum when their case finally makes it to immigration court. But they say migrants know that if they claim asylum, they essentially will be allowed to stay in America for years.

“People aren’t necessarily coming to apply for asylum as much to access that asylum adjudication process,” said Andrew Arthur, a former immigration court judge and fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates for less immigration in the U.S.

Some of what lawmakers are discussing would raise the bar that migrants need to meet during that initial credible fear interview. Those who do not meet it would be sent home.

But Paul Schmidt, a retired immigration court judge who blogs about immigration court issues, said the credible fear interview was never intended to be so tough. Migrants are doing the interview soon after arriving at the border from an often arduous and traumatizing journey, he said. Schmidt said the interview is more of an “initial screening” to weed out those with frivolous asylum claims.

Schmidt also questioned the argument that most migrants fail their final asylum screening. He said some immigration judges apply overly restrictive standards and that the system is so backlogged that it is hard to know exactly what the most recent and reliable statistics are.

WHAT IS EXPEDITED REMOVAL?

Expedited removal, created in 1996 by Congress, basically allows low-level immigration officers, as opposed to an immigration judge, to quickly deport certain immigrants. It was not widely used until 2004 and generally has been used to deport people apprehended within 100 miles of the Mexican or Canadian border and within two weeks of their arrival.

Defenders say it relieves the burden on the backlogged immigration courts. Immigration advocates say its use is prone to errors and does not give migrants enough protections, such as having a lawyer help them argue their case. As president, Republican Donald Trump pushed to expand this fast-track deportation policy nationwide and for longer periods of time. Opponents sued and that expansion never happened.

WHAT MIGHT THESE CHANGES DO?

Much of the disagreement over these proposed changes comes down to whether people think deterrence works.

Arthur, the former immigration court judge, thinks it does. He said changes to the credible fear asylum standards and restrictions on the use of humanitarian parole would be a “game changer." He said it would be a “costly endeavor” as the government would have to detain and deport many more migrants than today. But, he argued, eventually the numbers of people arriving would drop.

But others, like Schmidt, the retired immigration court judge, say migrants are so desperate, they will come anyway and make dangerous journeys to evade Border Patrol.

"Desperate people do desperate things,” he said.