Donald Trump’s company “cultivated a culture of fraud and deception” by lavishing luxe perks on executives and falsifying records to hide the compensation, a prosecutor told jurors Thursday during closing arguments at the Trump Organization’s criminal tax fraud trial.

Assistant Manhattan District Attorney Joshua Steinglass' fiery summation followed defense arguments that sought to focus blame for the fraud on longtime company finance chief Allen Weisselberg, who has admitted scheming to avoid paying personal income taxes on a company-paid apartment, luxury cars and other goodies.

“Weisselberg did it for Weisselberg," Trump Organization lawyer Michael Van der Veen said, punctuating his closing argument with the defense team’s mantra during the monthlong trial.

Steinglass pushed back when it was his turn, telling jurors: “Both halves of that sentence are wrong. It wasn’t just Weisselberg doing it and it wasn’t just Weisselberg who benefited.”

The Trump Organization, the entity through which the former president manages his real estate holdings and other ventures, is accused of helping Weisselberg and other executives avoid paying income taxes on company-paid perks.

Steinglass told jurors that the Trump Organization — through its subsidiaries Trump Corp. and Trump Payroll Corp. — is liable because Weisselberg and an underling he worked with on the scheme, controller Jeffrey McConney, were “high managerial” agents entrusted to act on behalf of the company and its various entities.

Steinglass will finish his closing argument on Friday.

If convicted, the Trump Organization could be fined more than $1 million. It could also face some difficulty making future deals.

But company lawyers argued that Weisselberg was only intending to benefit himself with his tax dodge scheme, not the Trump Organization, and that the company shouldn’t be blamed for his transgressions.

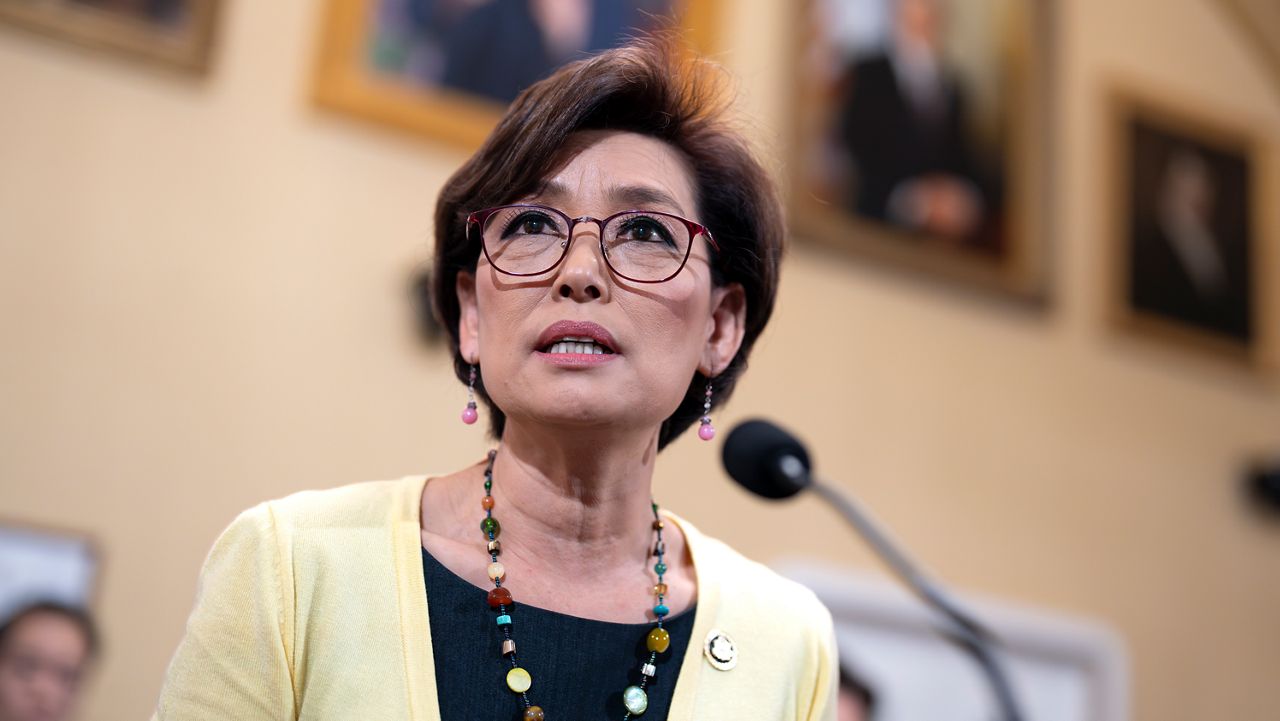

“We are here today for one reason and one reason only: the greed of Allen Weisselberg,” Trump Organization lawyer Susan Necheles said, her remarks accompanied at one point by the wail of a siren from an emergency vehicle outside.

The tax fraud case is the only trial to arise from the Manhattan district attorney’s three-year investigation of Trump and his business practices. Thursday's closing arguments were the last chance for prosecutors and defense lawyers to sway jurors before they deliberate next week.

Manhattan D.A. Alvin Bragg watched from the courtroom gallery as Steinglass spoke.

Weisselberg pleaded guilty in August to dodging taxes on $1.7 million in extras and testified against the Trump Organization in exchange for a promised sentence of five months in jail.

Weisselberg, now a senior adviser, has worked for Trump's family for nearly 50 years, starting as an accountant for his real estate-developer father Fred Trump in 1973 before joined Donald Trump’s company in 1986.

“Along the way, he messed up. He got greedy. Once he got started, it was difficult for him to stop,” Necheles said.

Necheles argued that the case against the company is tenuous and that the 1965 state law underlying some of the charges requires prosecutors to show Weisselberg intended to benefit the company, not just himself.

Weisselberg testified that he conspired to hide his perks with McConney by adjusting payroll records to deduct their cost from his salary.

The arrangement reduced Weisselberg’s tax liability, while also saving the company money because it didn’t have to give him a hefty raise to cover the cost of the perks and additional income taxes he would have incurred.

“I knew in my mind that there was a benefit to the company,” Weisselberg testified.

But Necheles argued that any benefit to the company was ancillary, minimal and unintentional.

“He is atoning for his sins, but as part of the plea deal the prosecution forced him to testify against the company he helped built,” Necheles told jurors. “Now the prosecution’s case rests on one thing: convincing you, the jurors, that Mr. Weisselberg’s actions were done in behalf of the company.”

“You are going to see there was no such intent,” Necheles added. “The purpose of Mr. Weisselberg’s crimes was to benefit Mr. Weisselberg.”

The arguments got off to a rocky start as Necheles was caught showing jurors portions of witness testimony that had previously been stricken from the official court record.

Judge Juan Manuel Merchan admonished Necheles after prosecutors objected to the display — the latest dust-up involving Trump Organization lawyers. He halted arguments so she could remove any other precluded testimony from her slideshow.

Necheles said the error wasn’t intentional and apologized to the jury when she resumed her argument after a half-hour break.