Unless lawmakers in Congress can come to an agreement on a funding deal to avert a shutdown in two days — a prospect growing unlikelier by the minute amid divisions in the House Republican conference — the government will shut down after midnight on Saturday.

Democrats and Republicans in the Senate have moved ahead with a bill that will keep the government running through mid-November while also providing funding for FEMA disaster relief and aid to Ukraine. But House Speaker Kevin McCarthy — facing a revolt in his own caucus from far-right members pushing for deep spending cuts and some even calling for his ouster — has said that the Senate’s bill is a nonstarter in the Republican-controlled lower chamber.

Here’s what happens if the government shuts down and what that could mean for you.

In May, President Joe Biden and Speaker McCarthy reached a deal to suspend the country’s debt limit through 2025 in exchange for setting spending limits for two years. Both chambers of Congress overwhelmingly passed the debt limit agreement, which President Joe Biden signed into law in June.

But far-right members of the House Republican conference rejected the deal, saying it didn’t go far enough to cut spending, and staged a revolt in retaliation earlier this summer, blocking consideration of a package of bills and paralyzing the House floor. The group ultimately convinced McCarthy — who has a razor-thin majority in the House — to walk away from the agreement.

In order to fund the government, Congress must pass 12 annual appropriations bills by the beginning of the fiscal year on Oct. 1 — something that lawmakers have done just a handful of times in the last 47 years, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Typically, Congress would package those bills together into one massive bill known as an omnibus — like the one President Biden signed into law late last year ahead of Republicans regaining control of the House. But once McCarthy gained the speaker’s gavel, he vowed a return to the “regular order” of passing the dozen appropriations bills.

The House has moved forward with spending bills far below the levels agreed to in the accord between Biden and McCarthy, meaning they’d be dead on arrival in the Senate and certainly would not win the president’s signature.

As of Friday, the House has passed four of those bills — for Defense, State Department and Foreign Operations, Homeland Security and Military Construction and Veterans Affairs, the first three of which were passed on Thursday night. The Senate has not passed any.

If the government grinds to a halt at midnight on Oct. 1, some federal government operations would shut down, while others would continue, until Congress takes action.

Some programs that are outside of the annual appropriations process — like mail delivery and key entitlement programs Medicare and Social Security — are not impacted.

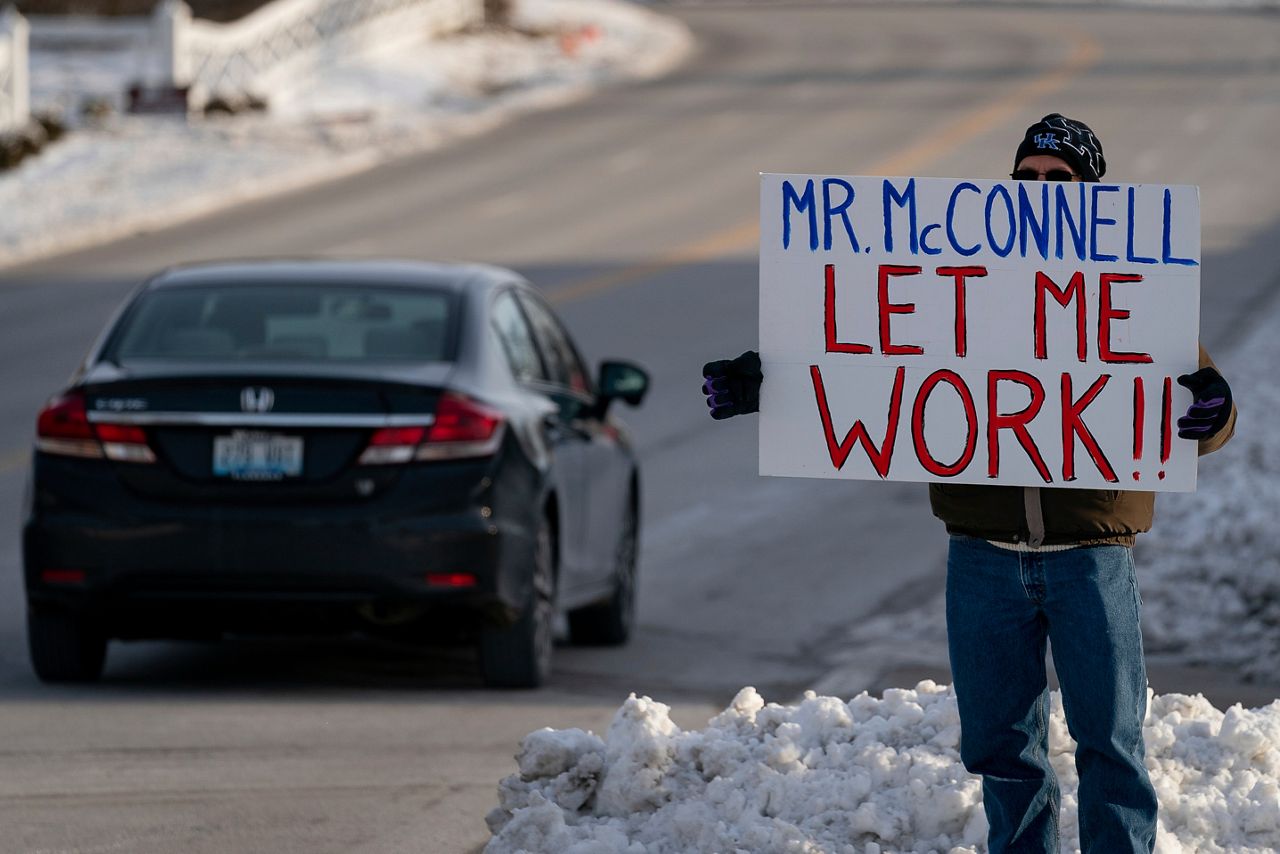

But millions of federal employees and members of the military will not get paid until a shutdown ends — and though they’re guaranteed retroactive pay after a shutdown is resolved, that could mean hardships for millions of American families.

Additionally, non-essential employees would be furloughed, with the federal government warning that some will be sent home without a clear date to return to work.

Government contractors could also be laid off, but unlike federal employees, they are not guaranteed back pay when the shutdown ends.

But government functions that are deemed essential will continue — and employees that are deemed essential would be asked to work without pay. That typically includes air traffic controllers and TSA screeners, most Customs and Border Protection agents, military service members and others.

On a call with reporters on Tuesday, White House National Security Council Coordinator for Strategic Communications John Kirby stressed that with the government shut down, U.S. military servicemembers, including 1.3 million active-duty troops, would still have to show up to work without getting paid.

“Republicans are playing partisan politics here with American lives, with our national security,” he said.

Biden administration officials this week have warned that a shutdown would impact millions of Americans, including disrupting small business loans, disaster recovery projects, nutrition assistance programs and air travel.

In an interview with Spectrum News, Kirby noted that “hundreds of thousands” of Pentagon employees could be furloughed, which would impact military recruitment.

“Most recruiters are active duty members, of course, but they are backed up by civilian employees in those recruiting offices and in headquarters,” he said. “It could have an effect on our ability to bring in fresh troops from the military.”

The White House this week circulated state-by-state data for the seven million “vulnerable moms and children” that rely on government assistance for food, WIC “serves nearly half of babies born in this country.” If the government shuts down, the White House estimates the food assistance would dry up within days.

“During the course of a shutdown, millions of those moms, babies, and young children would see a lack of nutrition assistance,” Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said, estimating that WIC would last “a day or two” and even states with funding reserves would likely run out within a week.

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has repeatedly emphasized that a shutdown would halt air traffic control training, an area that has seen staffing shortages, as well as negatively impact the work the Biden administration has done to reduce flight delays and cancellations.

“There is no good time for a government shutdown, but this is a particularly bad time for a government shutdown, especially when it comes to transportation,” Buttigieg warned at a briefing on Wednesday. “The consequences would be disruptive and dangerous.”

Buttigieg said in an interview with Fox News on Friday of travel disruptions that will “mount each day” that a lapse in government funding continues.

“I know that sometimes federal workers get portrayed as sort of pushing paper and the work they do doesn’t matter,” Buttigieg said Friday. “Some of the people that are gonna get pulled off the job in my building are the people developing the process to make sure that you could get compensated if an airline is responsible for you being delayed for hours and hours and it’s their fault. This is stuff that matters to people.”

Interior Department officials said that the majority of the country’s 425 national park units will be closed to the public during a shutdown, a move that could lose the system collectively 1 million daily visitors and the small communities that surround them as much as $70 million. But the governors of Arizona and Utah said they will use state funds to keep some of their most iconic parks — like Zion National Park and the Grand Canyon — open for business.

According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonprofit that looks at fiscal issues, there have been 20 “funding gaps” since the modern budgetary process began in 1976, though the concept of a government shutdown did not begin until a few years later.

In the early 1980s, U.S. Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti authored a series of opinions which determined that government agencies did not have the authority to keep running if Congress did not pass funding to keep them running.

Thus, the government shutdown was born — though he later advised that work necessary for the “safety of human life or the protection of property” would have to continue.

The length and severity of these shutdowns have widely varied. While Ronald Reagan saw 8 shutdowns during his presidency, the most of any president, some lasted just a few hours, and some saw no federal employees furloughed.

All told, there have been 10 government shutdowns that involved federal employees being furloughed: One under Jimmy Carter, three under Reagan, one under George H.W. Bush, two under Bill Clinton, one under Barack Obama and two under Donald Trump.

The lengthiest shutdowns were a 16-day shutdown in 2013 under Obama over attempts by Republicans to defund the Affordable Care Act, the 21-day shutdown in 1996 after a dispute between Clinton and the GOP-controlled Congress, and the 35-day shutdown over Trump’s demand to fund construction of a border wall between the U.S. and Mexico from December 2018 to January 2019, the longest in history.