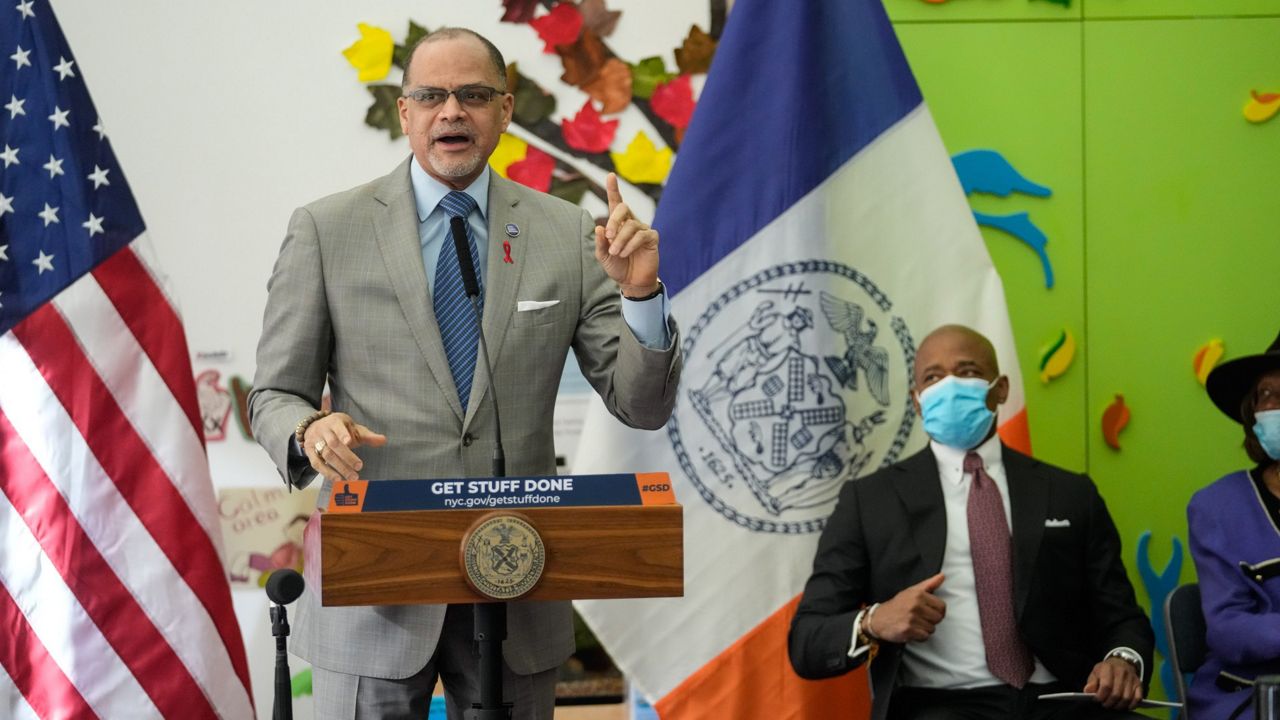

Back in December, Mayor Eric Adams and Schools Chancellor David Banks made a promise: “By this spring, all of our special education students in pre-K and 3-K will have the supports they need to flourish both in the classroom and in life,” Adams said.

“This expansion will open enough pre-K seats to serve every single preschool child with disabilities across the five boroughs,” Banks added.

But with spring just about over, they’re not there: more than 300 children who need a seat do not have one.

What You Need To Know

- In December, Mayor Eric Adams and Schools Chancellor David Banks promised to provide a special education pre-K seat for every child who needs one by this spring

- But as the school year ends, there are still more than 300 children entitled to a seat who do not have one

- Advocates say the city should hire its own teachers and open its own classrooms to fulfill its promise — and legal obligation — to serve all children

“We're glad that the [Department of Education] has made progress this year in opening more preschool special education classes. But the job is not yet done. Right now, there are still more than 300 children waiting for seats in preschool special education classes,” said Randi Levine, policy director at Advocates for Children.

For years, hundreds of children with disabilities went without special education seats they were legally entitled to, in part because pre-K special education teachers in schools that contract with the city were paid much lower than their peers.

In December, the city announced a contract enhancement that would give those schools extra money, so they could pay teachers more competitively, and open up more seats. And Deputy Chancellor Kara Ahmed says it has led to an increase in children being served.

“In just a matter of a few months, our team was able to create nearly 700 special class seats based on data, so based on where the data tells us there's an actual need so that families and their children have immediate access to the education that they're entitled to,” she told NY1.

The city had initially promised to open 800, which officials had said would be enough to serve all children who need a spot — a mark they have not hit, and, with the number of children waiting, still would not be enough to meet their promise of serving every child in need.

Ahmed says the city is still working to open more seats.

“We're working closely with our special ed colleagues to understand, to your point, that 300-plus number, where are those seats actually needed? What types of seats are needed?" Ahmed said.

She says the contract enhancement has also helped pre-K providers stabilize about 6,500 existing special education seats, and transition them to a longer school day.

“Through increased pay, we're able to increase the likelihood of retaining teachers. When we can retain teachers, we can keep classrooms open,” Ahmed said.

But Levine, from Advocates for Children — who joined the mayor and chancellor back in December at their announcement — says the city can and must do more.

“If there aren't enough community based organizations to open the classes that are needed, then the Department of Education needs to open its own classes to serve every child who needs a preschool special education class,” she said.

The city has launched some of its own integrated classes, where children with and without disabilities learn together. And Ahmed repeatedly noted the city was looking to serve the children who need a seat in the least restrictive environment.

But Levine says the city has only funded teachers for those classes, not related services — like physical, occupational, or speech therapists that children with disabilities often need to function well in a less restrictive classroom.

“So we're also in a situation where Department of Education administrators and parents are reluctant to place children in some of those integrated settings, because they're concerned that the children won't receive their mandated speech therapy and other services there,” she said.

Just last week, Advocates for Children released a report showing that more than 10,000 preschool students with disabilities did not have a single session of a service like speech therapy, or a visit from a special education teacher.

Ahmed says she understands time is of is of the essence to fix these gaps.

“Children get one chance at being three, at being four. They don't get a do-over,” she said. “And so we worked very quickly in a matter of months to make this progress happen, but there's still more to be done. And our commitment is to make sure that it is.”

)