Nestled mid-block between buildings on West 17th Street in Chelsea sits a nondescript, three-story yellow brick building that has been vacant for about seven years.

Nearly 160 years ago, however, the building housed “Colored School No. 4,” one of the city’s last “colored” schools from the segregationist era.

Now, advocates hope to secure a landmark designation for the site that will preserve its history.

What You Need To Know

- Advocates hope to secure a landmark designation for a building on West 17th Street in Chelsea that once housed "Colored School No. 4," one of the city's last "colored" schools from the segregationist era

- Built around 1853 originally as a schoolhouse for white children, it operated as a “colored” school, a segregated school for African American students, from 1860 to 1894. It was one of the two last remaining “colored” schools in New York City when it closed

- In February, the Landmarks Preservation Commission began the process of designating the former school a historic landmark, according to an LPC spokesperson. A public hearing was held in April and the LPC is scheduled to vote on the proposal on May 23

Built around 1853 originally as a schoolhouse for white children, it operated as a “colored” school, a segregated school for African American students, from 1860 to 1894. It was one of the two last remaining “colored” schools in New York City when it closed.

Its exterior is largely unchanged from its schoolhouse days, but the interior of the building is in rough shape. A failing roof has allowed water to seep into the building, exposing it to the elements.

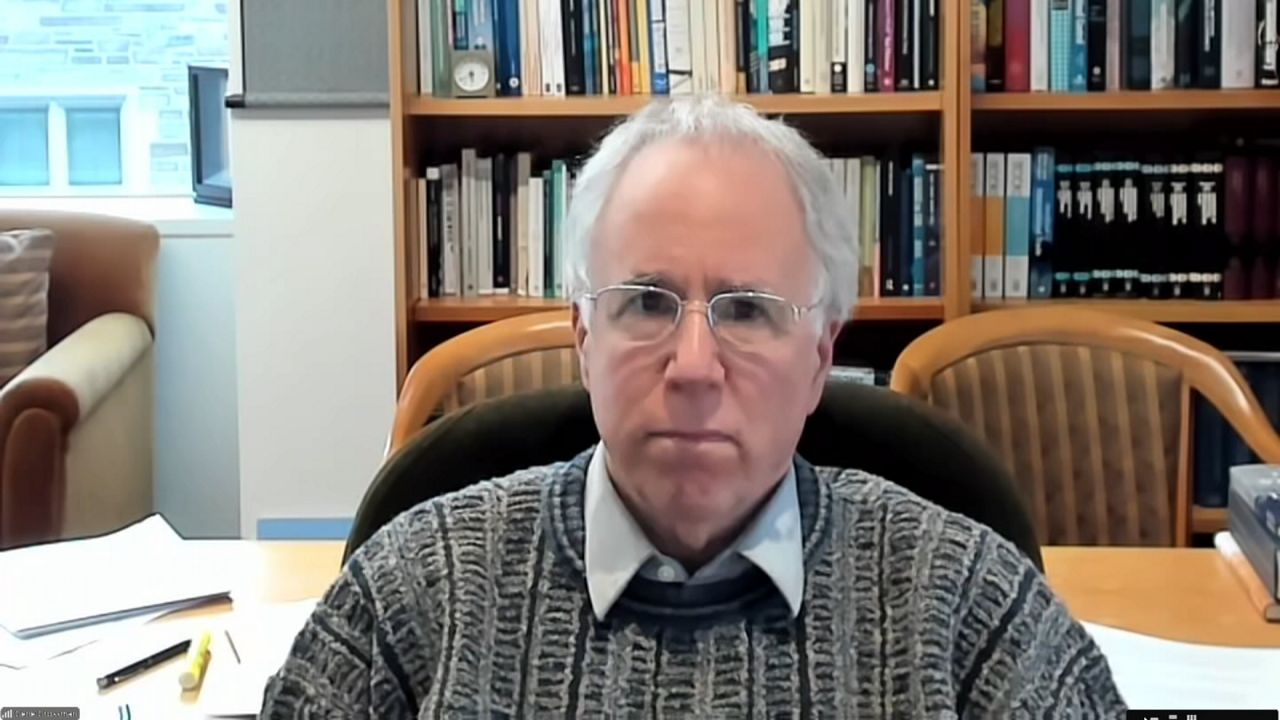

This has added urgency to a four-year-long campaign, led by historian and author Eric K. Washington, to landmark the building as historic with the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission.

“In New York, things come and go so quickly, and it's always a marvel to find something that has survived a lot of the changes with the passing of time,” Washington said.

Washington found out about the school as he was writing his book “Boss of the Grips: The Life of James H. Williams and the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal” in 2018.

He discovered that Williams was a student at the school in the 1880s and 1890s, he said. After some digging, he confirmed that the building on West 17th Street, between Sixth and Seventh avenues, was the same building standing there since the 19th century.

Williams, the protagonist of Washington’s book, went on to become the chief Red Cap Porter at Grand Central Terminal.

“This turned out to be an iconic occupation associated with African American men, and he was the first Black Red Cap in the country,” he said.

Red Caps were charged with carrying passenger suitcases. The position became an iconic profession for African American men at the time, often serving as a gateway to other career paths, according to Washington.

Williams was known for hiring young Black men, mostly college students. At a time when employment opportunities were limited for this community, the Red Cap position opened up doors for many who took up its ranks, including Paul Robeson and Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

Others continued along their career paths after doing stints as a Red Cap, successfully forging their way as clerics, journalists, linguists, actors, athletes, politicians and civic leaders, Washington said.

All of this can be traced back to the influence and legacy of “Colored School No. 4,” Washington said.

He first submitted a proposal to the commission in 2018, but didn’t get much success moving the effort forward.

“I needed to kind of up the ante,” he said.

He started spreading the message about the history of the building — which went into city ownership after the school shut down in 1894 and was most recently used as a lunchroom for the Department of Sanitation — with the local community, elected officials, various historic associations and more.

When he presented his case at the local community board’s land use committee meeting for the first time in 2018, they unanimously got on board, and followed up with a letter to the commission in support of the proposal.

“The community board thinks that it's really important to maintain these buildings as a critical reminder of our segregationist education policy in history, which nobody really knows about,” Kerry Keenan, co-chair of Community Board 4’s Chelsea Land Use Committee, said in an interview.

She said the community board was surprised to learn of the building’s history in the neighborhood.

“It's really vital to preserve something like this, the last remaining 'colored' school in Manhattan, and to commemorate African American heritage in the city,” she said.

In February, the commission began the process of designating the former school a historic landmark, according to a Landmarks Preservation Commission spokesperson. A public hearing was held in April.

“The Landmarks Preservation Commission is considering designating the former Colored School No. 4 as a landmark because it is important as Manhattan’s only known surviving example of a racially segregated school from the period between the Civil War through the post-Reconstruction era,” wrote an LPC spokesperson.

“The school afforded crucial opportunities and skills to Black students as they struggled against the discrimination and inequities that were part of their daily life,” the spokesperson added.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission is scheduled to vote on the proposal on May 23.

The City Council member who represents the district, Erik Bottcher, supports the push to landmark the building.

Bottcher coordinated a visit last December, when community members walked through the building for the first time.

“We saw firsthand how much water damage has taken place in the building,” he said. “There's a big puddle on the roof every time it rains, and that is leaking into the building. The top few floors in the back are virtually destroyed by water.”

Bottcher said the state of the building has made efforts to preserve it a priority.

Landmarking the building would safeguard attempts to demolish it without the commission’s approval. It would also safeguard against attempts to alter the exterior facade without city approval. There would also be a plaque placed outside explaining the building’s history.

It would not, however, provide for funds to repair the building.

“I'm also fighting in the budget for the money to shore up the building to repair the roof and to save the building,” Bottcher said.

Bottcher is hoping the building can eventually become a cultural center focused on the African American experience in New York City.

“This will be a rich asset not just for our district, but for the entire city,” he said.

It’s a sentiment shared by Washington as well, who said the school’s contribution to New York City history highlights the greater ebb and flow of African American migration throughout the city over time.

“When you think of Blacks in New York, your mental compass immediately goes way uptown to Harlem,” Washington said. “But Blacks in New York are not just about Harlem, and [the school] makes that connection between these two neighborhoods and other neighborhoods.”

It also serves to recognize some of the prominent people who walked through those doors back then.

Sarah J. S. Garnet, for whom a nearby elementary school was renamed in 2022, was a principal of “Colored School No. 4.” A leading suffragist, she led many of her schoolchildren to safety after a white mob attacked the school during the Draft Riots of 1863.

Though the exterior of the building is unremarkable, the fact that it still stands mostly unchanged since its time as a schoolhouse is part of its legacy.

“If you blink, you miss it. But once you realize it's there, then all of a sudden the mind reels,” Washington said.

_Pkg_NYPD_Cop_NJ_Shooting_Clean_131152335_3440)