Last summer, the city’s parks were flush with maintenance crews as New Yorkers streamed into green spaces after a long pandemic winter.

The parks department was able to hire about 3,500 workers, their salaries paid with a one-time injection of federal COVID-19 relief funds, to pick up litter and protect greenery amid another spring awakening as part of the City Cleanup Corps program.

Now, there are 1,800 federally funded workers left, after about half of the original crew has left the jobs.

With a diminished number of workers, the department is projecting that at the July peak of the high season of parks usage – with lawns, trails, beaches and pools seeing daily use – there will be 259 fewer total cleanup workers than last year.

In addition, by the end of the season, without additional funding, those workers will also face a severe bottleneck to stay employed: Only as many as 400 of the maintenance workers could get permanent jobs in the department.

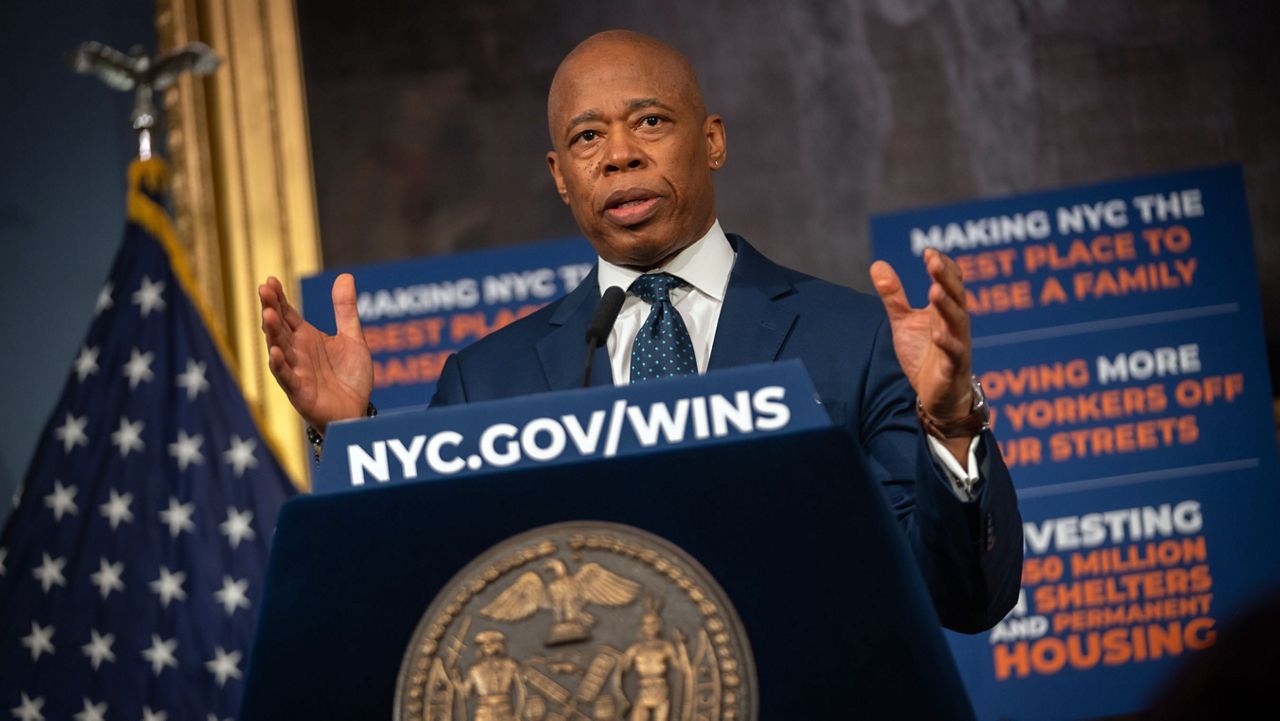

In the final weeks of budget negotiations, City Council members and labor leaders are trying to urge Mayor Eric Adams’ administration to add millions more in funding to cover the maintenance jobs.

They are pushing him to honor a campaign promise of funding the parks department at 1% of the city’s total budget, which would nearly double his last proposal of $600 million, which is down $20 million from last year’s spend. Adams has called the number a “down payment” on greater funding.

Park advocates say that without full funding, the relative drop in conservation for parks will land harder on marginalized neighborhoods.

“There are huge inequities in green space and the care for green space in our city,” Councilman Shekar Krishnan, who chairs the parks committee, said in an interview Thursday. “We need to see a continuation of all the positions we’ve had until this point.”

At a City Council budget hearing Friday, Krishnan and other members questioned parks department officials over maintenance levels and job opportunities for cleanup workers. The hearing comes about six weeks out from the deadline for the adoption of the city budget.

Overall, the city says it expects to have 4,431 maintenance staff during the height of the summer season, down from 4,690 last year.

This represents a “minimal decrease” overall, said Megan Moriarty, a spokesperson for the department, said in an emailed statement. She added that Adams’ latest spending plan adds new funding to support the 400 permanent, year-round maintenance positions that Cleanup Corps workers can apply for.

“This will allow for a more stable workforce with the ability for more staff to be dedicated to a single location rather than relying on mobile crews,” Moriarty said.

Yet the projected drop in maintenance crews will hit some boroughs harder than others, according to numbers provided by the parks department.

Last July, the Bronx had 1,047 workers. This year it will see a drop of 225 positions, to 822.

Brooklyn is seeing its total number of maintenance workers increase by 10, while Manhattan will get two more.

The department said it allocates maintenance crews based on both foot traffic and according to the city’s list of districts that have seen the greatest impact from the pandemic.

Without additional funding, the parks department says, the disparity in cleaning crews over last year will only grow into the fall, with staffing levels down by nearly 900 positions in November and December compared to the same time in 2021.

Yet Sue Donoghue, the parks commissioner, said in Friday’s hearing that the loss of the hundreds of workers will not affect the conditions of the city’s green spaces.

“We don't anticipate a negative impact,” Donoghue said. “Although there is no doubt those workers are important to us.”

Adam Ganser, the executive director of the advocacy group New Yorkers For Parks, said in an interview before the hearing that the rise and fall in staffing numbers can make residents feel uncertain about the care being given to their green spaces, and puts unexpected burdens on workers.

“That yo-yo effect really puts a tremendous strain on the parks department staff itself,” Ganser said. “If our parks are looking like they are in terrible shape, it reflects really poorly on the city as a whole, and people start to feel insecure in their lives in the parks.”

The workers who are facing the loss of their jobs are the lowest paid in the union that represents them, Local 983, according to Joe Puleo, the union’s president. Many of the workers, who make minimum wage, turned to the jobs after being laid off during the pandemic.

“These are the people that need these jobs the most,” Puleo said. “This is the difference between them paying their rent and not paying their rent, or getting food.”

Puleo estimated that the city could hire the entire Cleanup Corps group for about $40 million.

“When it comes to the city’s budget, this would be like a nickel in your pocket,” he said.

Those job losses won’t come in full until the end of the summer season, because the parks department paid to extend their contracts past April when federal funds ran out, until Sept. 15, at the end of the high season.

David Stark, the park’s department’s executive financial officer, said in the council hearing that only a small portion of seasonal hires compete for full time jobs, and the the Cleanup Corps sees a regular attrition of about 100 people a month. Yet he underscored that there is still no guarantee of continued work for most of the Cleanup Corps workers.

“There's no moving from a seasonal line directly into a full-time line without an interview process,” Stark said at the hearing.

Still, he said, competition for the open permanent roles will be stiff.

“We do not want people to leave that want to stay with parks,” Stark said. “But at some point there’s going to be limitations.”

Stark said that workers who do not get roles will be eligible for department-run training programs that seek to place workers in full-time roles in the city’s public housing agency or in the schools, often working in food service.

Giving those workers full time positions in the parks department, however, would put them on the track to becoming park supervisors after several years and multiple exams – roles that earn an annual salary of about $100,000.

“There is a grave disparity there,” Krishnan said in the hearing. “This will have a direct impact on workers who rely on these positions, on their families.”

_Pkg_Kyng_Davis_Clean)