Nightlife is back. Classrooms are mostly maskless. Unvaccinated Brooklyn Nets star Kyrie Irving is on the court at Barclays Center.

Here comes BA.2.

By one metric — cases per 100,000 people — Manhattan recently passed a threshold for a “medium” level of alert, according to guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The city has said that it will change its own alert level based on citywide case counts.

The strain of COVID-19, a sub-variant of omicron, now represents the majority of test samples in New York state, and cases are beginning to tick up in the five boroughs. On Friday, the city’s new cases on a seven-day average hit nearly 1,400, up from just under 600 about a month before.

The subvariant is about 30% more contagious than the virus that caused the last wave of winter infections, and health experts are saying that the city should prepare for a continued rise in cases, albeit those that lead to fewer hospitalizations than before.

While the next wave will likely wreak less havoc than previous ones, health experts say that disparities in vaccinations and precautionary measures across different city neighborhoods will mean BA.2 could further widen the disparate impacts of the pandemic on vulnerable communities.

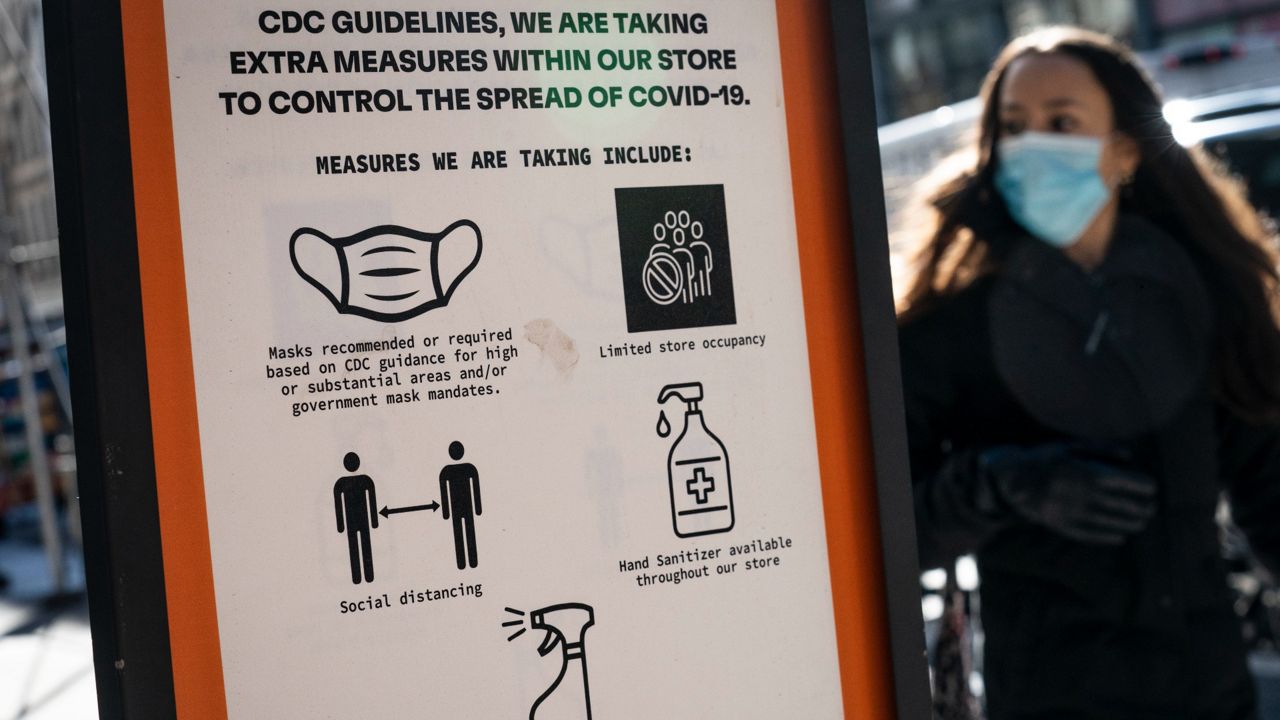

“If we’re seeing differences in masking rates, differences in social distancing, differences in ventilation in lower-income neighborhoods, then you're likely to see differences in outcomes as well,” said Dr. Bruce Y. Lee, a professor at the CUNY School of Public Health.

The BA.2 wave is coming in the wake of Mayor Eric Adams relaxing COVID-19 safety policies and rules in recent weeks, even as countries in Europe, where trends have typically foreshadowed infections in the U.S., saw spikes in cases because of the subvariant.

Restaurants, entertainment venues and gyms no longer have to require proof of vaccination from patrons. Public schools do not have to enforce mask wearing in classrooms for children aged 5 and up. City-based performers and athletes, such as Irving, are now exempted from the vaccination mandate for private employers.

Adams has defended his decisions to relax pandemic-era rules as necessary to rejuvenate the local economy and return city life to a pre-pandemic rhythm.

“I was not elected to be fearful, but to be fearless,” Adams said in March when announcing the expanded vaccination exemption for performers and athletes. “I must move this city forward.”

The changes “didn't seem to be epidemiological decisions as much as they were political decisions,” said Chris Palmedo, an associate professor of health communications at the CUNY School of Public Health.

But, Palmedo said, the mayor has done “better than average” in explaining his reasoning behind the policy changes, and has been consistent in saying he wants to loosen restrictions while allowing room to move slower if need be.

On Friday, Adams said he would keep the mask mandate for the city’s youngest students, citing rising cases in schools.

Yet Lee fears that Adams’ decisions have created a general laxity in the city around COVID precautions, which is compounded by the difficulty the city is facing in measuring the severity of the incoming BA.2 wave.

Testing has dropped sharply in recent months, and many people now use at-home rapid tests, for which there is no method to report results to the city, meaning test positivity, and case counts, are not accurate.

Other stand-in metrics, such as hospital visits and virus samples in city wastewater, are helping somewhat to round out the picture.

“It’s almost like piecing together these very disjointed pieces to try and figure out what's happening,” Lee said.

There are reasons for optimism and pessimism in confronting the BA.2 wave, according to Dr. Jay Varma, a professor at Cornell University who served as a top health adviser to former Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Pessimism, Varma said, because even countries like the United Kingdom that have strong booster vaccination coverage have seen relatively high numbers of hospitalizations.

Optimism because some laboratory studies suggest that vaccinated people who were infected with the first version of omicron — which infected many across New York City — have strong protection against BA.2.

Cases are ticking up in New York City, but it is happening slowly, Varma said, and emergency room visits for COVID-like illnesses, such as respiratory issues, are remaining low.

“This is the weird level of uncertainty that we have right now,” he said. “It provides me with some reassurance right now, that we're not seeing a rapid uptick. But that could change very quickly as it did with the first omicron wave.”

Health experts said that the coming wave is likely to only exacerbate existing health disparities between high- and low-income neighborhoods. Booster vaccination coverage already lags significantly behind in many vulnerable communities: Virtually no ZIP codes in the South Bronx, east Brooklyn or southeast Queens show adult booster rates higher than 40%, while Manhattan below 110th Street shows at least 60% coverage for nearly all areas.

Congress has also not passed a proposed COVID spending bill, which would include money for buying tests. On Monday, Senate leaders announced they had reached a deal on a version of the bill that did not include aid to developing countries; some House Democrats have said they would not vote for a bill that does not include global aid.

In the absence of the renewed funding, Elisabeth Ryden Benjamin, the vice president of health initiatives at the Civil Service Society, said she is concerned that uninsured Americans will forgo testing and vaccination because they will now be quoted for test costs that insurers used to cover, expecting federal reimbursement.

“I’m worried,” Ryden Benjamin said. “It’s gonna be a problem, and the bills are gonna come in, or people are gonna be afraid to get care.”

There are between 500,000 and 600,000 uninsured New York City residents, Ryden Benjamin said, primarily people without immigration documentation.

Those residents can receive free testing from city-run sites, Varma said, but he said he was frequently frustrated by the city’s difficulty in effectively getting that information out.

The city has yet to change its alert level to medium, something the health commissioner, Dr. Ashwan Vasan, said Friday it will likely do “in a matter of weeks.” Adams said the city will distribute six million rapid tests over the coming months from mobile sites.

Lee said he would like to see the city take more precautions now, since the data suggest that BA.2 is already rapidly spreading through the population.

If the city waits to hit certain thresholds, he said, the lack of strong metrics tracking the virus means that the actual level of infections will be much higher than the number that triggers the change, suggested in the “medium” alert level, to recommending increased mask wearing, or reinstating the vaccine requirement for restaurants.

“Once you do that, you're kind of too late,” he said.