New York City has long been a favored spot for the world’s wealthy to invest in an asset that holds value, provides access and comes with a veil of secrecy: luxury real estate.

Now those penthouse apartments and landmarked townhouses are coming under strong scrutiny amid an international crackdown on the Russian economy as it invades Ukraine.

Alongside waves of sanctions aimed at crippling the ruble, Western countries are considering targeting the billionaire “oligarch” class of captains of Russian industry who have influence inside the country.

In New York, that requires piercing the layers of shell companies, trusts and limited liability companies that wealthy foreigners often use to obscure their ownership of pricey homes.

Some elected officials and experts in shadowy international investing are now calling for the city and state governments to expand laws that require transparency in real estate.

“There’s an elaborate system, a legal shell game, essentially, that has been used for years, and the city and state can help to pierce through that,” Mark Levine, the Manhattan borough president, said Friday after a rally in support of Ukraine.

New York City leaders for many years encouraged foreign investment in luxury real estate, even as it became clear that many such buyers had gotten their wealth through shady means.

A 2015 New York Times investigation found that homes in Midtown Manhattan's Time Warner Center ostensibly owned by LLCs were bought by powerful business and economic leaders from countries such as Russia, Malaysia and Mexico who have been accused of misdealings and embezzlement.

In an interview in 2013 in New York Magazine, former Mayor Michael Bloomberg said that taxes paid by wealthy foreigners helped prop up the city’s schools, healthcare system and public safety.

“Wouldn’t it be great if we could get all the Russian billionaires to move here?” Bloomberg said.

In 2019, New York state enacted a law that required LLCs buying and selling property in the state to include a disclosure form of the names of all people connected to the company, including when those LLCs were themselves owned by other LLCs.

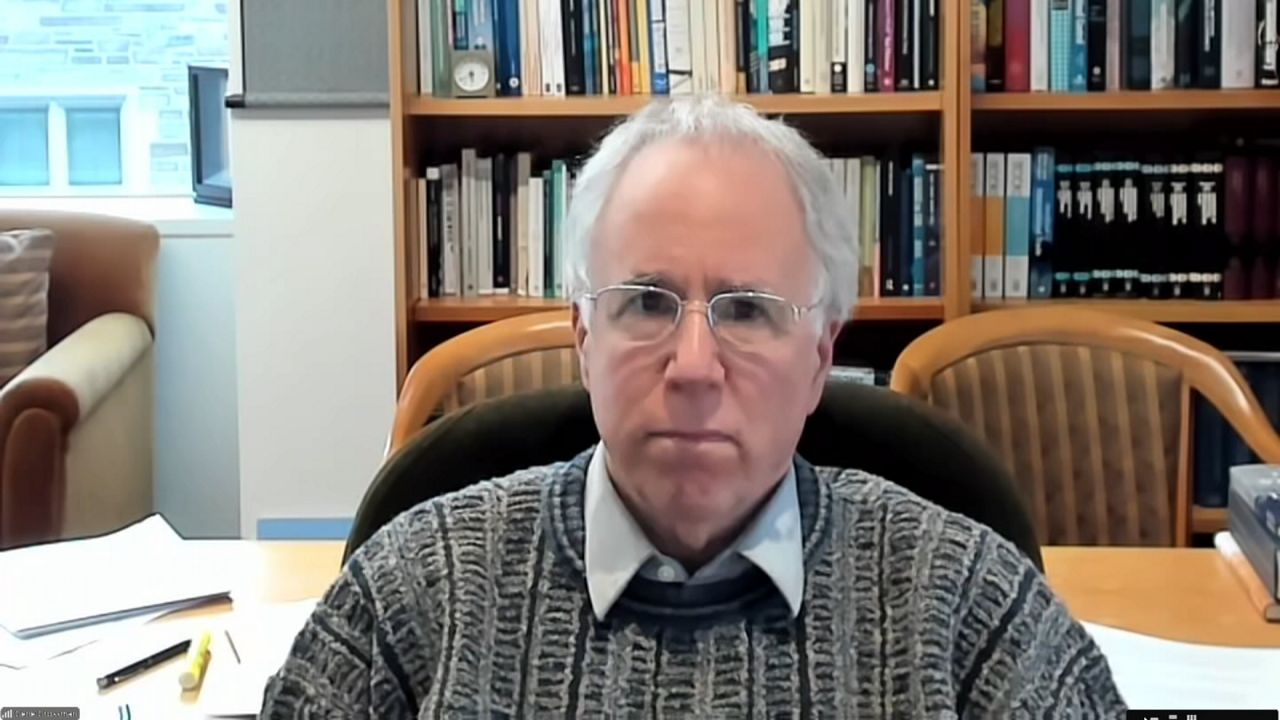

Yet Russian oligarchs often obscure their ownership of assets like real estate by having associates purchase them in their name, making even such legally required disclosures ineffective, according to Elisabeth Schimpfössl, an associate professor of sociology at Aston University, in Birmingham, England, and the author of “Rich Russians: From Oligarchs to Bourgeoisie.”

“It would probably be under a name that would be almost impossible to identify,” Schimpfössl said.

That means it’s difficult to know, Schimpfössl said, if recent sanctions levied by the U.S. against people in the inner circle of Russian President Vladimir Putin will have any impact in New York City’s real estate market.

While some Russian oligarchs – such as Oleg Deripaska and Roman Abramovich – have reportedly bought some (very expensive) homes in New York City, the extent of local real estate assets held by the Russian bank leaders and top government aides targeted in last week’s sanctions is less clear. (Neither Deripaska nor Abramovich have been sanctioned by the U.S. over the Russian invasion of Ukraine, though they have been sanctioned previously.

Experts on shadowy foreign investing say that the U.S. has made important strides toward better transparency for all-cash purchases in recent years.

The U.S. Treasury has designated New York City as one of nine special jurisdictions around the country for which it requires special disclosures of foreigners buying real estate in all cash transactions above $300,000. In October, the Treasury renewed the special designation through April 2022.

In January 2021, the Corporate Transparency Act became federal law. The law requires all companies, including LLCs, to report information to the government on every beneficial owner of the companies.

Yet neither the new law nor the Treasury’s special disclosure rules require that the actual owners of corporate entities be made public, and the Corporate Transparency Act has yet to be implemented, said Ian Gary, executive director of the FACT Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for closing tax loopholes and promoting financial transparency.

The U.S. is also the only country in the G7 group, which includes the U.K., another hub of oligarch money, that doesn’t have anti-money laundering obligations for real estate agents and other people involved in the real estate industry, Gary said.

“My main concern now is the weaknesses around our current regime,” Gary said. “We can’t just take away their yachts if we don't know where they are.”

Gary said that the New York City Council, or the state government, could pass laws that require public disclosure of all owners of large real estate assets.

“We need to make our system less vulnerable to these problems in the first place, and we need to make our economy much more hostile to dirty money, so we're not trying to pick up the pieces when a crisis happens,” Gary said.

Yet any new laws requiring financial transparency need to move beyond just real estate transactions to be effective, according to Casey Michel, the author of “American Kleptocracy: How the U.S. Created the World's Greatest Money Laundering Scheme in History.”

Michel said that oligarchs and others looking to park ill-gotten cash in American assets have diversified, and that any new city or state laws need to reflect that.

“It’s no longer just the luxury penthouses, condos, and high-rises,” Michel said. “Now it’s office space, it’s port facilities, it’s manufacturing plants and steel plants.”

_Pkg_NYPD_Cop_NJ_Shooting_Clean_131152335_3440)