As the first Black woman to seek the presidential nomination from a major party, Shirley Chisholm broke barriers and cemented a legacy that can be felt across the nation. But in Brooklyn, where Chisholm was born and raised, her legacy is deeply felt among the politicians who have followed in her footsteps.

“I'm living breathing proof that you can be what you see,” said Crystal Hudson, the newly elected council member representing neighborhoods in Brooklyn, including Bedford-Stuyvesant, where Chisholm spent her formative years.

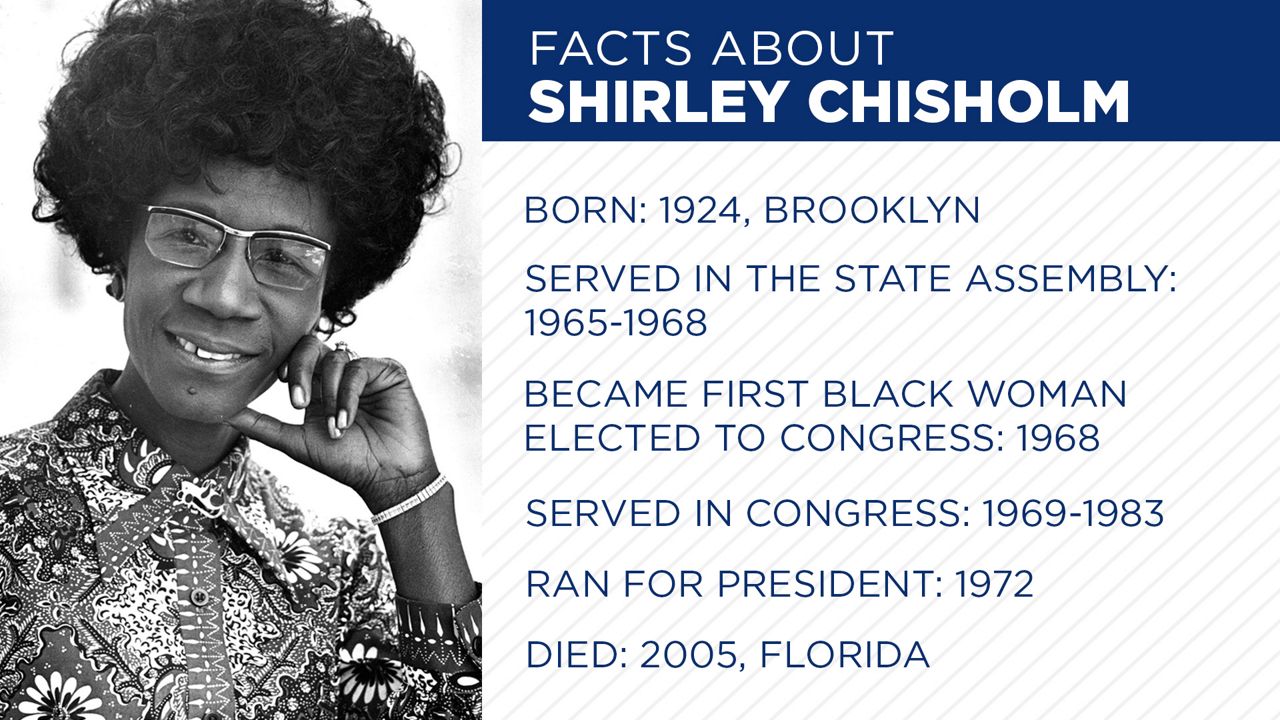

Chisholm, the daughter of immigrants from Barbados, was raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant, graduated from Brooklyn College and as an elected official, represented Central Brooklyn.

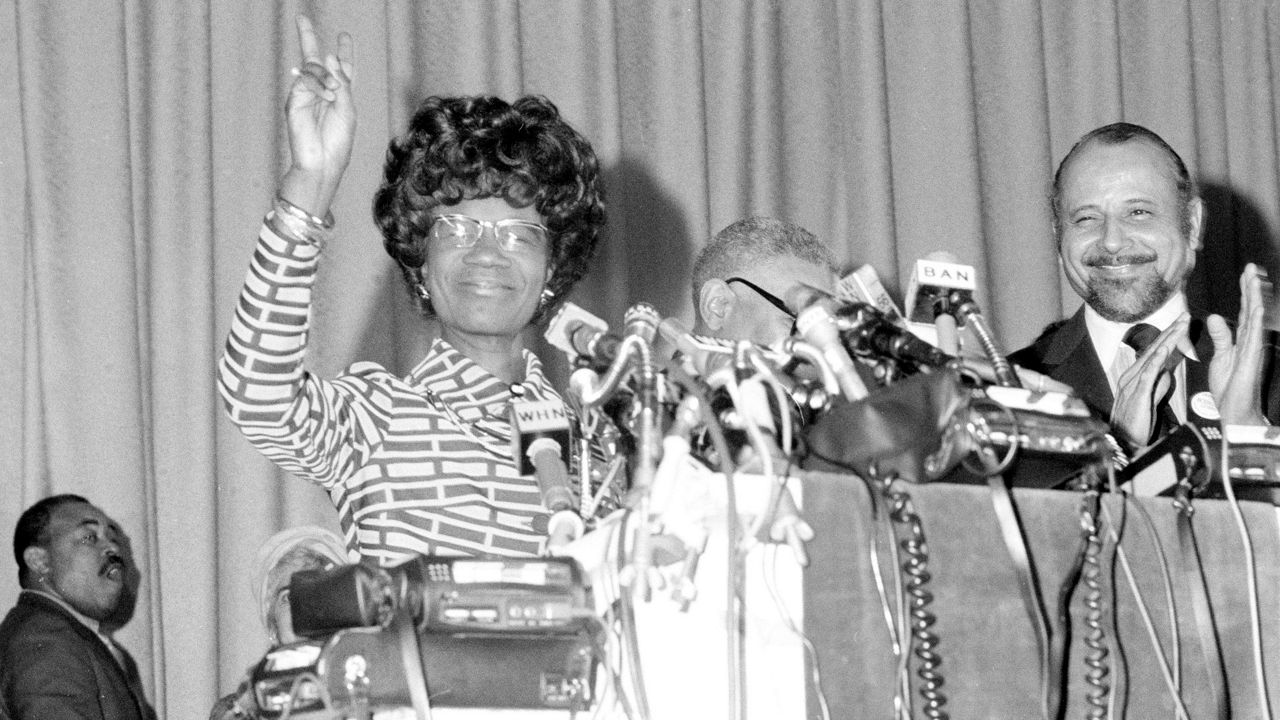

In 1972, she ran in the presidential election, seeking the nomination of the Democratic Party. She faced intense discrimination during her run, including being blocked from participating in televised primary debates. After taking legal action, she was permitted to make one televised speech during her primary campaign.

Chisholm entered 12 primaries and garnered 152 delegate votes —10% of the total votes, despite a modestly funded campaign and pushback from the Congressional Black Caucus, according to experts.

“When she was running in ‘72, a lot of Black men [in the Congressional Caucus]—they wanted a Black man first and they said so,” said Barbara Winslow, professor emerita at Brooklyn College and founder and director emerita of the college’s Shirley Chisholm Project.

The U.S. has yet to elect a woman to the highest position in government, but in 2020, Kamala Harris, who is Black and Indian, became the first woman and woman of color to become vice president.

For many Black women in politics, they draw a direct connection between Chisholm’s trailblazing career and their own.

Hudson points to the barriers Chisholm, who died in 2005 at 80 years old, broke through not only with her presidential run, but also as the first Black woman elected to Congress.

“And I'm one of the first two gay Black woman ever elected in New York City and so there's a deep and strong legacy from which I come of Black women who have served as firsts here,” Hudson said.

It’s a legacy that state Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins also points to as inspiration.

“To see a woman make those kinds of strides certainly was part of my formative years,” said Stewart-Cousins, the first woman and Black woman, to lead a New York State legislative conference.

Stewart-Cousins calls herself a child of the 1960s, roughly the generation that came after Chisholm. But even she acknowledges that her full understanding of Chisholm took some time to develop.

“I think her personal journey became more impactful to me as I became older and understood, frankly, what she took on, how she took it on, and the dignity with which she faced a universal skepticism,” she said.

City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams, who is the first Black woman to hold the second-most-powerful position in city government, draws on two phrases Chisholm is known for.

“‘If they don't give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair,’” Adams said. “That's what I found to be pretty prevalent in my career and also ‘unbought and unbossed.’ Huge, huge mantras I think of a lot not just for me, but for many women and women of color.”

Still, political experts like Winslow believe that Chisholm’s legacy is only starting to be fully understood.

It’s the reason she founded the Shirley Chisholm Project in 2005, which houses an archive of documents, oral histories and more, to serve as a resource for anyone looking to find out more about the teacher, activist and politician.

“I don't think she's as well known as she should be,” Hudson said. “We don't have a national monument for her and until something like that happens and people can visit Shirley Chisholm and everybody knows exactly who she is then I think we've not done enough to honor her legacy.”

A statue honoring Chisholm was slated for 2020 at the Parkside entrance of Prospect Park in Brooklyn under a program by former Mayor Bill de Blasio, but was delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The city has yet to release details on the updated timeline for the Chisholm monument, but Adams said she expects efforts around this to pick up again soon.

Winslow, who authored the book “Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change (Lives of American Women),” partially attributes Chisholm’s perhaps underrepresented place in history to what she calls “pure rank, male chauvinism” and the racism she faced in her time.

She credits activists today, and particularly young people, with the current movement to reclaim Chisholm’s rightful place in history.

“It really begins with, in a sense in New York, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Me Too — that want more people of color in the forefront of the struggle and I think that that is why we can look back to Shirley Chisholm,” Winslow said.

She also points to Chisholm’s decidedly progressive stance on issues like reproductive rights, criminal justice and free education, as inspiring young people today.

The politicians following in Chisholm’s footsteps say they take personal responsibility for carrying Chisholm’s legacy forward.

“We have to just keep making sure people understand that the successes that we have, the positions that we have, were hard-fought and long-sought by so many people before us and they're not guaranteed,” Stewart-Cousins said.

_Queens_New_Trees_PKG_CG_FIX_2_134189101_23)