The outdoor dining sheds that changed the landscape of New York City’s streets during the pandemic may soon get packed up for good.

During a City Council hearing on Tuesday, Department of Transportation officials said that a revised outdoor dining program likely won’t feature sheds at all.

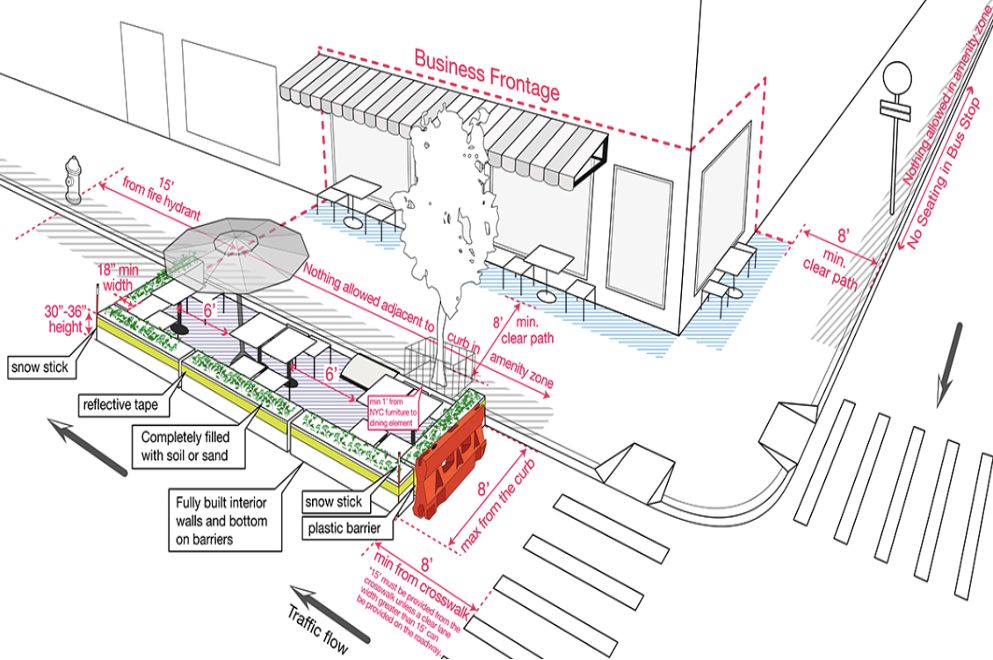

“We don’t envision sheds in the permanent program, we’re not planning for that,” said Julie Schipper, director of the Department of Transportation’s Open Restaurants program. “What would be in the roadway is barriers and tents or umbrellas, but not these full houses that you’re seeing in the street.”

Schipper testified at a hearing about legislation to turn the pandemic-era program into a permanent part of New York City.

She said the new program would be one “where you can dine outside when that feels nice and comfortable but you won’t need to be in a house on the street.”

Schipper added that restaurants that have set up sheds would not be grandfathered in and would need to get approval under a new plan beginning in 2023.

During the pandemic, restaurants, some of which spent significant sums of money to construct outdoor dining structures, were able to self-certify quickly, Schipper said.

“Going forward, there will be a full review so they will have to submit their plans that they plan to include,” she said. “We will review them and then if everything is in compliance then grant permissions for that restaurant to set up.”

But people in the restaurant industry who support the existing structures are hopeful that the permanent removal isn’t a done deal just yet.

“These are all aspects that still need to be discussed to determine what the most sustainable longtime solution is,” Andrew Rigie, executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, said. “There could be different setups in different areas where they work.”

Supporters of the Open Restaurants plan, which started under former Mayor Bill de Blasio, say it helped save the restaurant industry during the height of the pandemic.

“Outdoor dining reimagined what the city could do with our streets,” said Councilwoman Marjorie Velázquez, chair of the Committee on Consumer and Worker Protection and the prime sponsor of the bill to make the program permanent. “Welcoming outdoor spaces took over curbs and parks and sidewalks instead of just parked cars.”

But opponents say the outdoor dining structures are eyesores that have led to noisy and dirty streets, and have helped the restaurant industry at the expense of others.

“While we’ve created a program for restaurants, we haven't created a program for the shoe store next door, for the bookstore next to that, for the hardware store — that have all lost sidewalk space, that have all lost spots, that have all lost the attraction of a block to people wanting to shop there because it's now chaotic and anarchist,” said Councilman Kalman Yeger, who represents parts of Brooklyn including Bensonhurst and Borough Park.

The new proposal would move the jurisdiction of the city’s pre-pandemic sidewalk cafe program from the Department of Consumer and Workforce Protection to the Department of Transportation. It would also eliminate much of the red tape that was in place before the pandemic to establish outdoor dining, including zoning limitations.

Prior to the current outdoor dining program, the approval time to establish an enclosed sidewalk cafe could take more than a year, according to Velázquez. Multiple city agencies were involved in the approval process, including the Landmarks and Preservation Commission, Department of City Planning, Department of Environmental Protection, community boards, City Council and comptroller.

Outdoor dining was also not spread evenly across the city. Before the pandemic, 1,004 of the city’s 1,416 licensed sidewalk cafés were located in Manhattan, according to the Adams administration.

There are now 12,124 restaurants participating in the program, as of Feb. 1. In Manhattan, there are 5,909 restaurants participating in the program, 659 in the Bronx, 2,955 in Brooklyn, 2,414 in Queens and 187 in Staten Island.

“In the past, when I came in the ‘80s, you didn't see a single sidewalk restaurant in northern Manhattan. You didn't see it in the Bronx. You didn't see it in places in Brooklyn, Staten Island, and Queens — mainly composed of immigrant and working class [people],” said Ydanis Rodriguez, Department of Transportation commissioner.

Enforcement of outdoor dining regulations, which include size and distance guidelines, was also a concern raised during the hearing.

The city has issued 4,292 warnings and removed 40 structures since July 2020, according to officials.

“Enforcement has been very frustrating the last couple of years,” said Councilman Erik Bottcher, who represents portions of Manhattan's West Side, including Chelsea and Hell's Kitchen.

He said his office found that 93% of the businesses participating in the program were out of compliance with at least one Department of Transportation regulation. Some of the violations were minor, but some included major violations such as blocking a fire hydrant, he said.

“We’re gonna be working with the NYPD, Department of Health and with all the agencies, but especially with you,” said Rodriguez, in response to Bottcher’s concerns around enforcement. “You are our ears.”

Other critics of the proposal, like Yeger, pushed back against the message that the program has been uniformly successful across the city.

“I think it’s been successful for the restaurateurs, for sure, because they've been able to increase the size of their space, not pay real property taxes on it, not pay rent on it and have the ability to get free space courtesy of NYC,” Yeger said.

He said the rest of New Yorkers who need to navigate the streets and other non-restaurant business owners are losing out.

Yeger said he supported the program at the onset of the pandemic because of the urgent economic conditions the city faced, but said the city is now past those urgent concerns as restaurants have now been open for some time.

Though council members acknowledged the critiques, many like Velázquez, argue that making the sheds permanent is still a step in the right direction.

“We are not seeking perfection,” she said. “We are seeking participation and partnership.”

For New Yorkers like Yoshi Padilla, who works at a restaurant in Queens, the presence of the outdoor dining structures has become an ingrained part of the city’s culture.

“It’s just so much a part of our everyday and of our income and of everything we do so that I don't even imagine it not being here anymore,” Padilla said.

The council is expected to continue reviewing the proposal, but no date has been set for a vote.