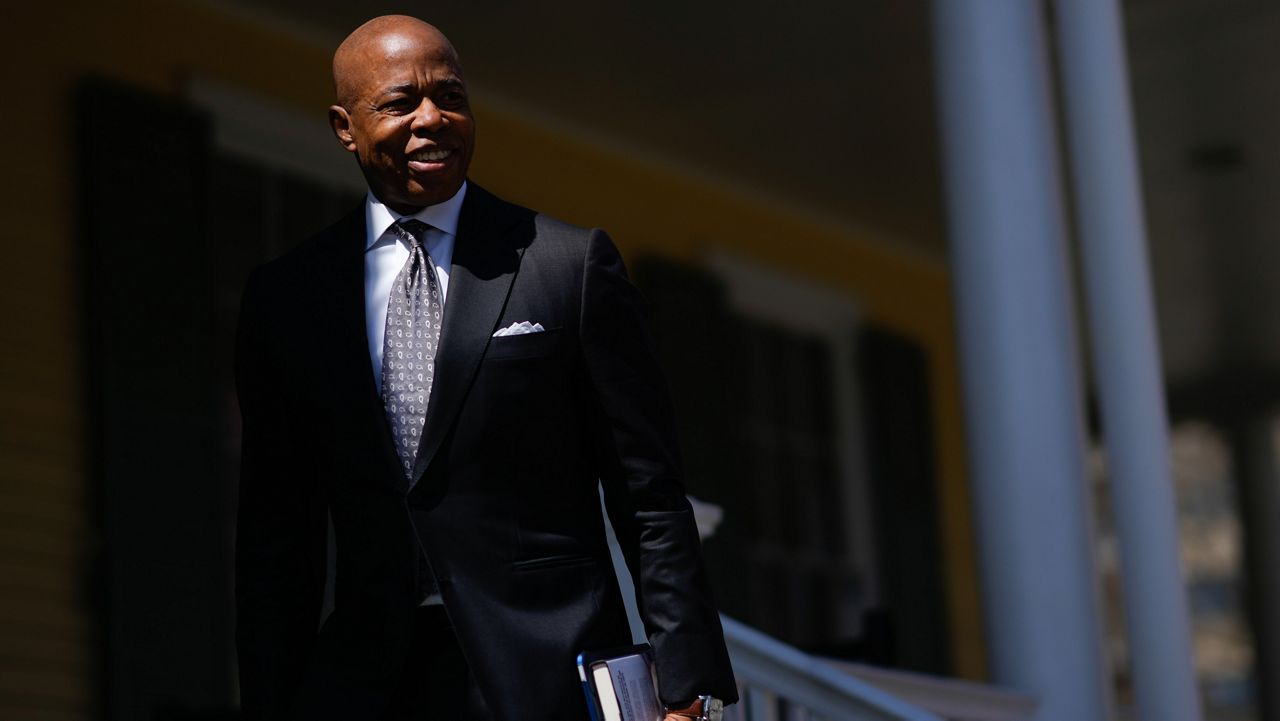

Mayor Eric Adams unveiled new traffic plans on Wednesday to improve safety conditions at intersections in an effort to reduce traffic fatalities.

Drivers and cyclists will now be required to fully stop at intersections that do not have a stop sign or a traffic signal when a pedestrian is present, and remain stopped until the pedestrian has crossed the street. There are 1,200 such intersections in the city. The city’s Department of Transportation will roll out an educational campaign this month about the new rule.

Adams also announced that police officers will be expected to double enforcement efforts for motorists that fail to yield to cyclists or pedestrians at intersections, as well as begin issuing warnings and, eventually, summonses for the new traffic rule, calling on patrol officers to enforce road rules alongside traditional traffic police.

"I don't subscribe to the theory that police officers should sit back and watch a traffic infraction take place and say, ‘That's not my job,’" Adams said at a news conference. “If they observe any form of traffic infraction or any form of illegal action, I expect them to take action.”

The transportation department will also begin constructing more raised crosswalks, with a goal of completing 100 annually, and will double the installation of design features in intersections like rubber speed bumps and plastic posts, which are meant to slow the speed of cars making turns.

Those design elements have helped reduce traffic injuries by 20% in recent years, said Ydanis Rodriguez, the city transportation commissioner.

The mayor’s office did not immediately respond to questions about the total cost of the education campaign for the new traffic rule or the cost of raised crosswalks.

The changes come as traffic fatalities reached a 10-year high in the previous fiscal year, and jumped by 30% from the year before, to 275 deaths, according to the 2021 Mayor’s Management Report. The majority of pedestrian traffic fatalities and injuries happen in crosswalks, according to data provided by the city.

“Traffic violence is a crisis that we don't talk about,” Rita Joseph, council member for the city’s 40th council district, said at the news conference. “We need to start having a conversation about deaths caused by crashes in the same way that we talk about gun violence.”

Adams’ new plans should be followed with a broader crackdown on unsafe vehicles in the city, as well as returning more street space for purely pedestrian use, Danny Harris, the executive director of the advocacy group Transportation Alternatives, said in an emailed statement.

“The concrete solutions announced today will better prevent drivers from speeding and protect our most vulnerable road users, like seniors, children, and everyone who bikes,” Harris said.

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio made traffic safety a central pillar of his administration, with his Vision Zero plan to reach no deaths or serious injuries from traffic collisions by 2024.

Fatalities fell from 249 in 2014 to 184 in 2018, before climbing back up in recent years.

Pedestrian advocates and elected officials have accused de Blasio of letting Vision Zero fall by the wayside, as well as initially opposing policies that would decrease car traffic, such as congestion pricing in Manhattan and creating pedestrian-only zones on certain streets during the pandemic.

De Blasio has repeatedly blamed the disruption of the pandemic — and the citywide uptick in car ownership — for the increase in traffic deaths. Traffic collision injuries are down in recent years, according to the Mayor’s Management Report.

Adams’ announcement of increased police enforcement comes a week after he announced that patrol officers will now be expected to regularly inspect subway stations for illegal activity as well as for homeless people.

The changes come amid ongoing concern from elected officials and criminal justice reform advocates over racially discriminatory policing patterns. Even as police stops have fallen dramatically in the city in recent years, Black and Latino New Yorkers are still stopped at significantly higher rates than white residents.

A new city law that took effect Jan. 1 now requires city police to document the age, gender and ethnicity of motorists and cyclists during traffic stops, with the purpose of curtailing discriminatory traffic policing.

Adams said that he did not want the increased enforcement actions to fall disproportionately on low-income workers, such as those who use e-bikes to make deliveries.

“Our goal is to be clear: People must learn the rules of the road or get off the road,” Adams said.