By about 9 p.m. on Sept. 1, Jennifer Moreno had managed to get both of her young boys — and herself — to sleep on the second floor of the home they share with her brother. That’s when the water started pouring into the basement.

“It was a matter of minutes,” Moreno said. “There was nothing you could do to save anything, because the water was coming from every direction.”

Her brother, who sleeps in the basement, emerged drenched but quickly donned a wetsuit to help neighbors save belongings and escape rising waters. Moreno and her sons made calls to friends nearby, urging them to get to higher ground.

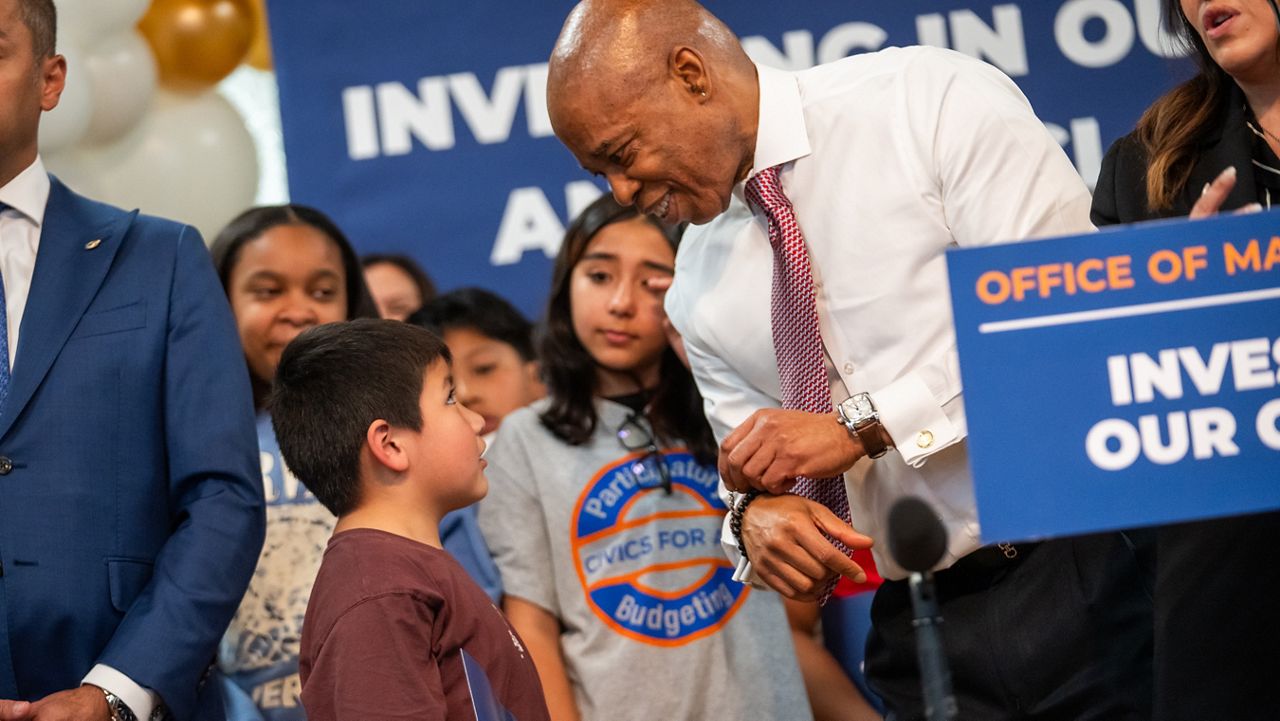

In the following days, her neighborhood in East Flushing, Queens, along with other parts of the borough that were hard hit by flash floods caused by the remnants of Hurricane Ida, saw visits from a string of politicians: Mayor Bill de Blasio, Gov. Kathy Hochul, Sen. Chuck Schumer and President Joe Biden.

Biden, standing in an alleyway by Moreno’s home, promised more than $100 million in disaster grants through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), capped at $34,000 per applicant.

Moreno is still waiting on her check, even though she knows the maximum grant would not make her whole: Contractors have estimated the cost to fix the flood damage at more than $100,000.

“Natural disasters, sewer backups, city problems, whatever it is, I didn't do anything wrong, to pay for all of these things that I've lost,” she said. “I’ve lost enough.”

Moreno is one of the nearly 19,000 Queens residents who applied for aid through FEMA, which has so far approved more than $34.2 million in assistance to borough residents, according to the agency. Yet locally, as nationally, the scale of the need has dwarfed the amount allocated for relief, with average payouts standing at just a few thousand dollars to families that have also suffered intense economic impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic.

What’s left are low-interest loans and limited grants from special city programs and through local housing organizations, with application processes that elected officials say are moving too slowly to make people safe before the winter.

“Quite frankly, I don't see any other option for these residents to rebuild, especially in light of the winter coming, without city assistance,” Queens Borough President Donovan Richards said. “I’m really worried. We’re in a state of emergency.”

'Really lowballing people'

Julia Nieves has already received her FEMA check: about $8,300, she said. Her contractors, however, have estimated her damage at more than $30,000.

She is already working on an appeal — something she said her neighbors have told her they don’t feel they have the time to work on.

She believes FEMA “doesn't want people to file an appeal, because there's so much baloney that goes into it.”

Nieves, 77, knows she is somewhat luckier than some of her neighbors: After calling into WNYC’s "Ask the Mayor" segment on Friday to tell de Blasio about her payout amount, she has received calls from City Hall staffers connecting her to information about other possible resources.

“I was in her basement,” de Blasio said at the Tuesday news conference. “She had many, many tens of thousands of dollars of damage, would be my estimate.”

Yet payouts typically represent a fraction of the cost to rebuild, with local residents, elected officials and housing organizations reporting grants as low as $2,000. That’s because FEMA’s grants are not intended to make disaster victims whole and are meant to fund only “basic repairs to make a home safe, sanitary and functional,” according to Michael Wade, a FEMA external affairs officer.

As of Oct. 18, FEMA said it had received 48,238 registrations for relief from Queens, the Bronx, Brooklyn and Staten Island, with $76.7 million approved in grants. Kristiana Sanford, a FEMA media relations specialist, would not provide the number of approved applications, or an average payout.

In an email, Sanford said “assistance is provided on a case by case basis. Each individual’s needs are different, and the grant amount can vary greatly depending on their specific case.”

According to copies of an internal FEMA dashboard summarizing relief efforts through Oct. 18 that NY1 obtained, the agency has already ruled out grants for 7.9% of New York state registrants for “insufficient damage.” In Queens, that number was 9.5%.

The dashboard shows that FEMA has inspected just under half of applicant properties.

At a Tuesday morning news conference, de Blasio criticized FEMA’s payout amounts, saying he was “disappointed” to hear that people facing significant damage were receiving only several thousand dollars.

“We’re gonna appeal back to them, to question that,” he said. “Because it sounds like they're really lowballing people.”

'I don't know what else to do'

Even with FEMA grants, Queens residents and others affected by Ida flooding are struggling to navigate a web of other possible relief sources.

In the Tuesday news conference, de Blasio suggested that there were some direct grants and low- or no-interest loans that the city itself could offer, but local advocates and elected officials say they have not heard about them. A spokesperson for the city’s Office of Emergency Management did not respond to a request for further information about New York City relief programs.

“Whatever they're saying they have available is not enough,” Richards said. “Quite frankly, I feel the city has been quite evasive at the moment.”

Though the city and state have made $27 million available through a fund to undocumented residents, elected officials say that will not cover the need, and that the federal government is steering relief applicants instead to Small Business Administration (SBA) loans.

“I’m so frustrated,” said State Sen. Jessica Ramos, who represents north central Queens. “I don't know what else to do to get our neighbors help.”

The SBA loans extend to $200,000 for homeowners and up to $2 million for businesses, with interest rates starting at 1.563% for homeowners and renters, according to Carl Dombek, a public affairs specialist with the SBA.

SBA conducts its own need assessments, Dombek said, and only loans to applicants who meet its eligibility standards.

“They have to have the ability to repay the proposed loan without the payment causing a hardship,” Dombek said in an email. “Credit does not have to be perfect, but it does have to be acceptable to SBA.”

According to the FEMA dashboard, the SBA loan program had denied loans to 6,501 applications out of 44,225 referrals through Oct. 18. The agency has approved 1,433 loans. The dashboard does not list reasons for loan denials.

In the absence of direct assistance, homeowners have little recourse to their standard house insurance policies, which typically do not cover damage from flooding that comes from outside the property. Few people in inland Queens neighborhoods have flood insurance policies through FEMA’s national program, which covers such damage. In Moreno’s ZIP code, 11369, there are 17 total policies out of more than 11,000 total housing units, according to FEMA data.

FEMA recently made sweeping changes to its flood insurance system, resulting in modest rate increases for most city policy holders. The changes have been met with criticism from city officials and Congress members.

“The folks that we have served, I can count maybe with one hand — and there will be fingers left — if they had flood insurance,” said Yoselin Genao-Estrella, the executive director of Neighborhood Housing Services of Queens.

Her organization has been able to secure limited funding from private financial institutions for grants to give to 10 to 15 families who received small amounts of federal aid, out of the more than 166 who have registered with them for assistance.

The city needs a more robust plan for disaster relief payments, Genao-Estrella said, drawing on public funds and private financial institutions that can quickly offer forgivable or low-interest loans.

The current approach ensures that rebuilding will not only be slow, she said, but that it will be done as cheaply as possible, losing out on opportunities to make vulnerable homes more resilient to climate effects. When the homes inevitably face flooding again, the process will start all over again.

“From what I see, we have a very broken and inadequate, not only physical infrastructure, but also our social service infrastructure,” Genao-Estrella said. “There needs to be money set aside. Right now we are going from Peter to Paul.”

Nieves and Moreno said that loans will not provide the necessary support for relief, especially for their neighborhood’s many retired couples who have lived in their homes for decades, and are now on fixed incomes.

“They’re not working anymore. Some of them can’t even afford to keep up their mortgage,” Nieves said. “They still have to worry about taking care of the inside of their home: Heat, hot water, food, the essentials.”

Moreno said she is working on organizing her nearby neighbors through a group chat to advocate for stronger relief grants, and serving as a support network as the crush of daily life is made almost unbearable by the added weight of rebuilding.

“We’re each other's counselors,” Moreno said after getting back from a neighbor’s house. “I’m getting anxiety filling out a form. She's crying looking at pictures. It’s so much more than the flood.”

“People are quick to forget,” she added. “And we’re still here living through it, day by day.”

------

Did you know you can now watch, read and stay informed with NY1 wherever and whenever you want? Get the new Spectrum News app here.

------

Looking for an easy way to learn about the issues affecting New York City?

Listen to our "Off Topic/On Politics" podcast: Apple Podcasts | Google Play | Spotify | iHeartRadio | Stitcher | RSS