Senate Republicans voted to block a bill passed by the House to raise the federal borrowing limit and continue to fund the government through December, putting the ball in Democrats' court to avert a shutdown and prevent the country from defaulting on its debts.

Democrats aiming to avert a shutdown are likely to try again — while simultaneously pressing ahead on President Joe Biden’s sweeping domestic agenda, adding another complicated factor as the party attemps to bridge their ideological divides.

The efforts are not necessarily linked, but the fiscal yearend deadline to fund the government past Thursday is bumping up against the Democrats’ desire to make progress on Biden’s expansive $3.5 trillion federal overhaul.

The bill, which would also provide $28.6 billion in emergency funding for those impacted by recent natural disasters and $6.3 billion to support Afghan refugees, failed 48-50, with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., changing his vote from "Yes" to "No" so the chamber can consider the bill again.

"Let me be clear: what the Republicans in the Senate did today is not normal," Schumer said after the vote, calling the actions of Republicans "one of the most reckless, one of the most irresponsible votes I have seen taken place in the Senate."

"The Republican Party has solidified itself as the party of default," the New York Democrat said, pledging "further action" to prevent default and avoid a shutdown.

Keeping the government open and avoiding default, Schumer said, is "vital to our country's future and we'll be taking further action to prevent this from happening this week."

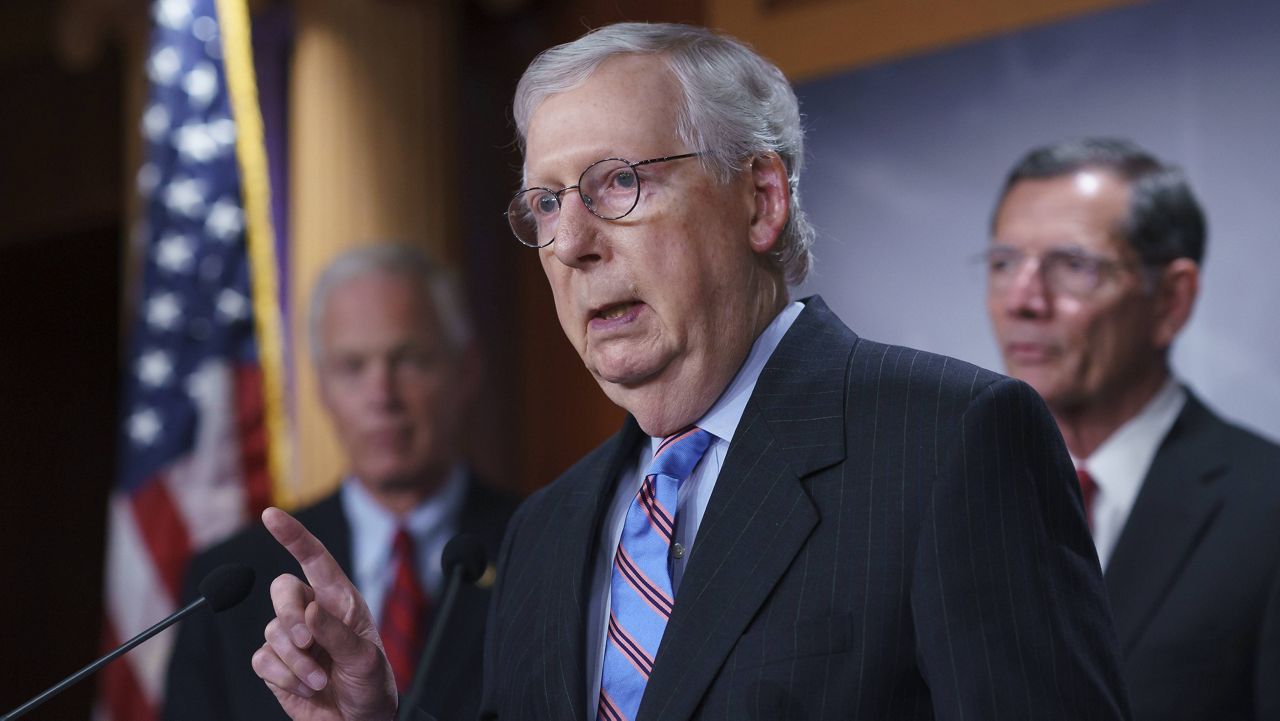

"For more than two months now, Senate Republicans have been completely clear about how this process will play out," Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said ahead of the vote Monday, noting that his party would support a "clean" funding measure to avert a government shutdown, but made his position on a debt hike clear: "We will not be supplying Republican votes to raising the debt limit."

With days to go, Democrats are likely to try again before Thursday’s deadline to pass a bill funding government operations past the Sept. 30 fiscal yearend, stripping out the debate over the debt limit for another day, closer to a separate October deadline.

Congress routinely raises or suspends the limit regardless of which party’s president is in the White House. But this time around, Republicans and Democrats are at odds. Members of the GOP, who are in the minority in both the House and Senate, are refusing to vote for raising the debt ceiling as a way of protesting what they see as reckless spending by Democrats, although raising the borrowing cap alone would not authorize any new spending, only pay off existing commitments.

Democrats believe both parties should share the responsibility of raising the debt limit, noting they voted three times with Republicans to do so under former President Donald Trump.

While they would prefer not to do so, Democrats indicated last week that they are prepared to go it alone when the House passed a bill that would suspend the debt limit through 2022 and fund the government through the end of this year. The measure faces an uncertain fate in the Senate.

While Congress still has time, the first step is already being taken. In 2019, lawmakers voted to suspend the debt limit through the end of July 2021. When the limit was reinstated, the Treasury Department began enacting what are called “extraordinary measures” so that the government can continue paying its obligations.

Those measures include pausing contributions to some government pension funds and other investments, suspending state and local government series securities, and borrowing from money that had been allocated to manage exchange rate fluctuations.

When those maneuvers are exhausted, the Treasury Department will then spend its cash on hand. It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact date that the department will be out of options, but it could be as soon as mid-October.

But what if the debt limit remains in place for too long? What would happen then? Click here to take a look at what economists predict the fallout would be.

Spectrum News' Ryan Chatelain and The Associated Press contributed to this report.