There was a period of several years in the wake of Sept. 11, 2001, when many of the middle and high school students whom Brett Schneider taught about the attacks had seen with their own eyes the towers burning.

In some cases they, or their teachers, showed signs of post-traumatic stress. The wounds were still open, and it kept classes from embarking on a broader accounting of the day’s tragedy and historical impact.

“Those first few years there was a lot of gingerness, because we couldn't know the context of who had lost who,” said Schneider, now the principal of the Bronx Collaborative High School.

By 2020, the last time Schneider taught 9/11 in person, there was one person on his school’s campus with a direct connection to the attacks.

With shifts in the city and the country, the way New York City’s educators teach about 9/11 has changed as well. The pandemic, policing and the politics of the Trump era have taken up more oxygen in recent years, leading to a tapering in the attention teachers and students have given to the attacks.

But just ahead of the 20th anniversary of 9/11, the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan and the rise, once again, of the Taliban, has given the subject a new life, teachers say.

“Right now a question that students are asking their teachers is, ‘Who got us into this war?’” Schneider said. “That discussion was not front and center for a long time. It had gone on for so many years that it wasn't on the tip of the tongue.”

City teachers say they often find it difficult to give the subject of the attacks its due. Though many schools will have special lessons on the anniversary each year, New York’s state educational standards only include discussion of the attacks in 8th and 11th grade.

With pressure to prepare students for year-end exams on a wide variety of subjects, many teachers stick to a circumscribed set of teaching points, said Elise Langan, an associate professor at Bronx Community College who studies and creates 9/11 curricula, and trains teachers across the country.

“The focus remains largely on how the United States was affected, and how it framed foreign policy,” she said. “Most teachers don't get into Guantánamo, or extraordinary rendition, or even conspiracies.”

In the early years, the teaching largely took place from a New York City perspective, Langan said, emphasizing the heroism of first responders and the emotional impact on the city.

Since then, many teachers have brought a broader shift in social studies education to 9/11, including lots of primary sources, and encouraging students to create historical narratives themselves, rather than take them from a textbook.

“It’s almost a journalistic approach,” said Tala Manassah, the deputy executive director of the Morningside Center, which creates social and emotional learning curricula and trains teachers. “You’re investigating to try and figure out, what happened here, how did it affect people, what is the fallout, what was the buildup?”

Even 20 years out, however, there are still frequent personal connections that local educators need to be wary of, said Sari Beth Rosenberg, who teaches social studies at the High School for Environmental Studies, in Hell’s Kitchen.

“Maybe don't show the pictures without trigger warnings,” she said. “That could be someone's uncle.”

Rosenberg says her and her colleagues’ approaches to teaching 9/11 have changed with the country’s political context. For many students, she says, it became personal again in the Trump years. Children of immigrants learned that the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency was created as a result of 9/11, and the “Muslim ban” of Trump’s first year in office echoed widespread Islamophobic attitudes in the wake of the attacks.

Yet other events and political trends with seemingly more direct relevance to everyday life in the city took precedence in classrooms.

“There are other huge issues, around police violence, for example, that in New York City are much closer to our kids' lives as current crises,” Manassah said.

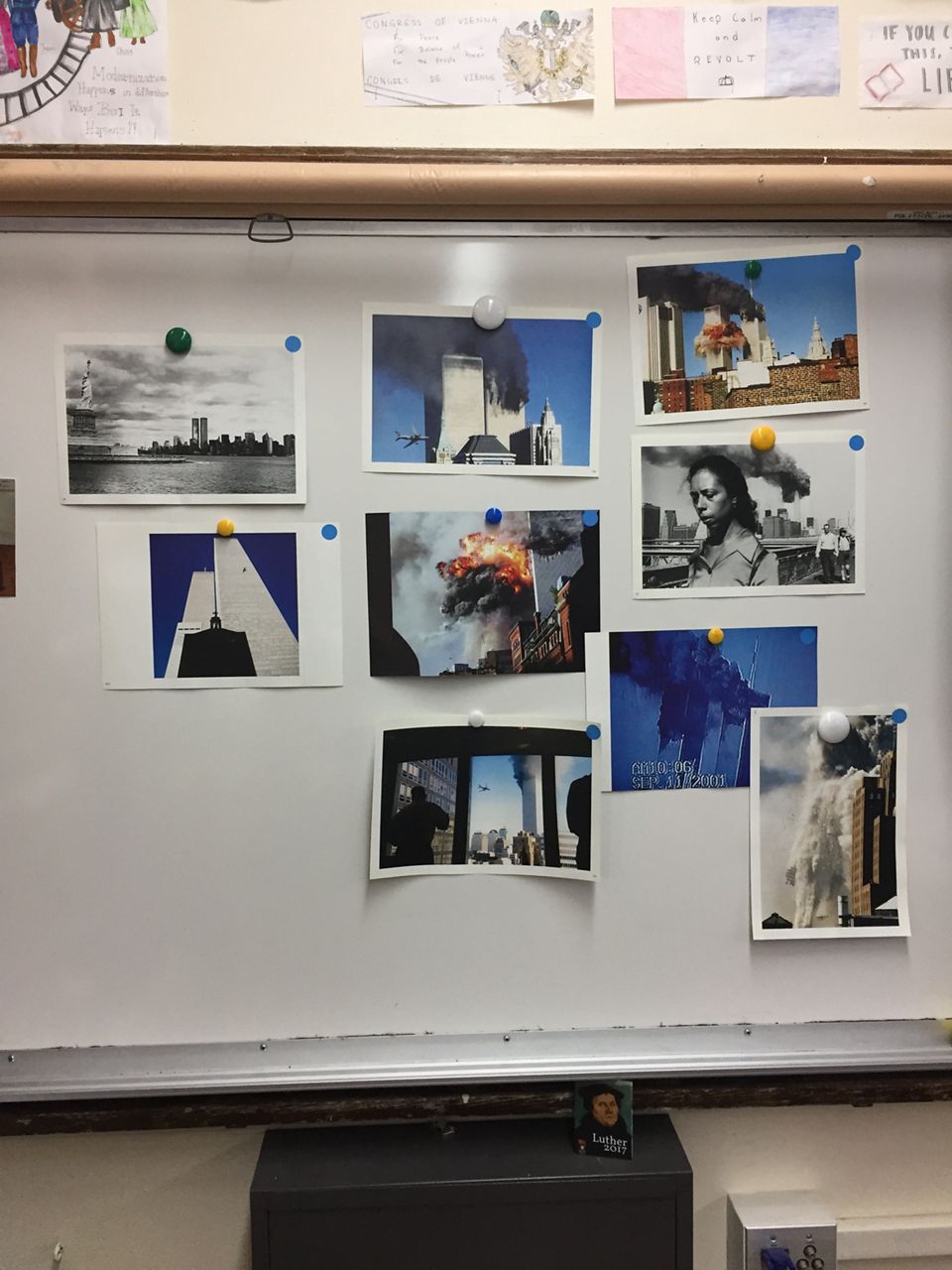

Four years ago, Sean McManamon, a social studies teacher at Brooklyn Technical High School, created a new photography-based 9/11 lesson for his 10th-graders because he had seen interest taper.

“It just kind of faded over time,” he said. “It wasn't current events anymore, and it wasn't quite history.”

The lesson asks students to examine photographs from the day, including famous and graphic photographs like the “Falling Man,” and curate and present them to the class. (He covers more graphic images with a slip of paper so students can choose whether to look at them.) He also talks about his personal experience on 9/11, watching the North Tower fall and learning that his cousin had died in the attack.

While sometimes other events McManamon teaches in his AP U.S. History class may not quite stick, he said, “The lesson has some heft to it.”

McMannon and Rosenberg now expect the withdrawal from Afghanistan to spur student interest — and give the study of 9/11 the strong resonance of a history lesson.

“I’m gonna use it as an opportunity to help them understand the importance of historical context,” Rosenberg said. “In order to understand why all these people are literally trying to jump on planes to get out of there, you need to back up 30 years at least.”

The renewed attention the attacks may get only underscores how 9/11 has shaped our world and our era’s politics, Manassah said, including our reliance on fossil fuels, women’s rights and military spending.

And even after 20 years, she added, it is still a deeply compelling story of the power of dignity and community.

“There are so many examples of the human capacity for compassion for healing, for helping, for showing up for other people that happened on that day and the weeks and months that followed,” Manassah said. “You should start there, but not end the story there.”