In the two years leading up to Aug. 4, survivors of child sexual abuse filed more than 8,263 civil suits in New York against their alleged abusers and the institutions that employed them.

Seven days later, that total jumped by nearly 1,000 to 9,241, according to data from the state’s Office of Court Administration.

The dramatic rise in cases is coming ahead of the end of a so-called “look-back,” or revival window for claims of child sexual abuse written into law with the Child Victims Act of 2019. The law changed the statute of limitations for such crimes, raising to 55 from 23 the age by which a person must file a civil claim for sexual abuse they experienced younger than 18. It also created a temporary period during which people older than 55 could also sue for childhood abuse.

That window, which allowed survivors to sue people and institutions for abuse dating to the 1970s and earlier, is ending as of Aug. 14.

Survivors and their attorneys are scrambling to get in under the deadline, after which the statute of limitations will once again be in effect.

The pandemic has added to the burden, plaintiffs’ lawyers say, disrupting the lives of people who may have planned to sue earlier but who were not able to contact a lawyer until now due to illness or economic hardship.

“The flood of calls is enormous right now, as people realize there is no more time,” said Jennifer Freeman, an attorney with the Manhattan-based Marsh Law Firm, who is overseeing CVA suits against major institutions, such as the Archdiocese of New York and the Boy Scouts of America. “They really have to make a decision.”

Between Freeman’s firm and another law firm they partner with on such cases, they have 20 lawyers working round-the-clock on fielding last-minute calls from survivors and writing and filing new complaints.

In many cases, the plaintiffs are suing multiple individuals and up to dozens of institutions, and there are also cases with up to 100 plaintiffs, she said, meaning the impact of the CVA suits filed so far is even greater than the nearly 10,000 cases reported by the state court system.

The pandemic has also had the effect of slowing down what is already often a slow process, with delays caused by moving the courts to remote hearings and institutions requesting extra time for document disclosure due to the emergency.

Freeman said that she has had some plaintiffs with cases pending die of COVID-19.

Last year, Gov. Andrew Cuomo extended the initial 12-month look-back window for another year because of the pandemic, but Freeman says it hasn’t been enough time.

“I don't know who hasn't been able to call me, because they’re still sick, or their loved one is still sick and suffering,” she said.

The delay has been frustrating for survivors who filed suit on the first day of the look-back window, like Rich Cardillo, a client at Freeman’s firm, who is suing the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York and a Catholic prep school in New Rochelle over a sexual assault he says he endured as a teenager in the spring of 1975.

Cardillo, 52, says that a member of the Congregation of Christian Brothers who taught at his school groped him and attempted to have sex with him while on a trip when Cardillo was 16. The incident derailed Cardillo’s life, he says, causing him to fear his growing feeling that he was gay and leading him to join the Christian Brothers, a teaching congregation that operates under the auspices of the Catholic Church, to stifle his sexuality.

In his application interview, Cardillo says, the Christian Brothers made him swear not to tell anyone about his abuse to join the movement.

“I felt I was not fit to be with another human being,” Cardillo said. “This was not the way I wanted to live my life.”

Cardillo, who lives in New York City, eventually left the Brothers, came out as gay to his family and found a partner, who died in 2012 after an 18-year relationship.

“I had to learn about intimacy,” Cardillo said. “I had to learn how to share my life with another person.”

Cardillo said that the archdiocese has slow-walked the discovery process so far by not handing over documents about the teacher’s many transfers between schools.

“Unless they were burned, they certainly exist,” he said.

Joseph Zwilling, a spokesperson for the Archdiocese of New York, said that it takes all allegations of abuse seriously, but cannot comment on individual cases.

In general, the larger the institution being sued, the more they have tried to delay the CVA cases, said Kevin Mulhearn, a plaintiff’s lawyer who is representing clients suing the Archdiocese of New York, Yeshiva University and ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who is facing criminal charges for sexual abuse in Massachusetts.

In part that is because the institutions are waiting for the look-back window to close so they will have a better grasp of their potential liability for payouts to survivors, Mulhearn said.

“That excuse is ending as of next week,” Mulhearn said. After that, “I expect that discovery will proceed at a much quicker pace, and I think many of these institutions operating in good faith will begin to try finding resolutions for the plaintiffs.”

The CVA has been destabilizing for those large institutions as well, said Marie Reilly, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Large institutions often rely on insurance companies to pay out damages for these kinds of cases, she said, and the possibility that insurance companies will suddenly be on the hook for alleged crimes that took place decades ago has wide, economically destabilizing effects.

“That’s not good for any of us, really,” said Reilly, who published a research article on New York’s Child Victims Act earlier this year. “It creates uncertainty in insurance markets that gets passed on to everyone that uses goods and services.”

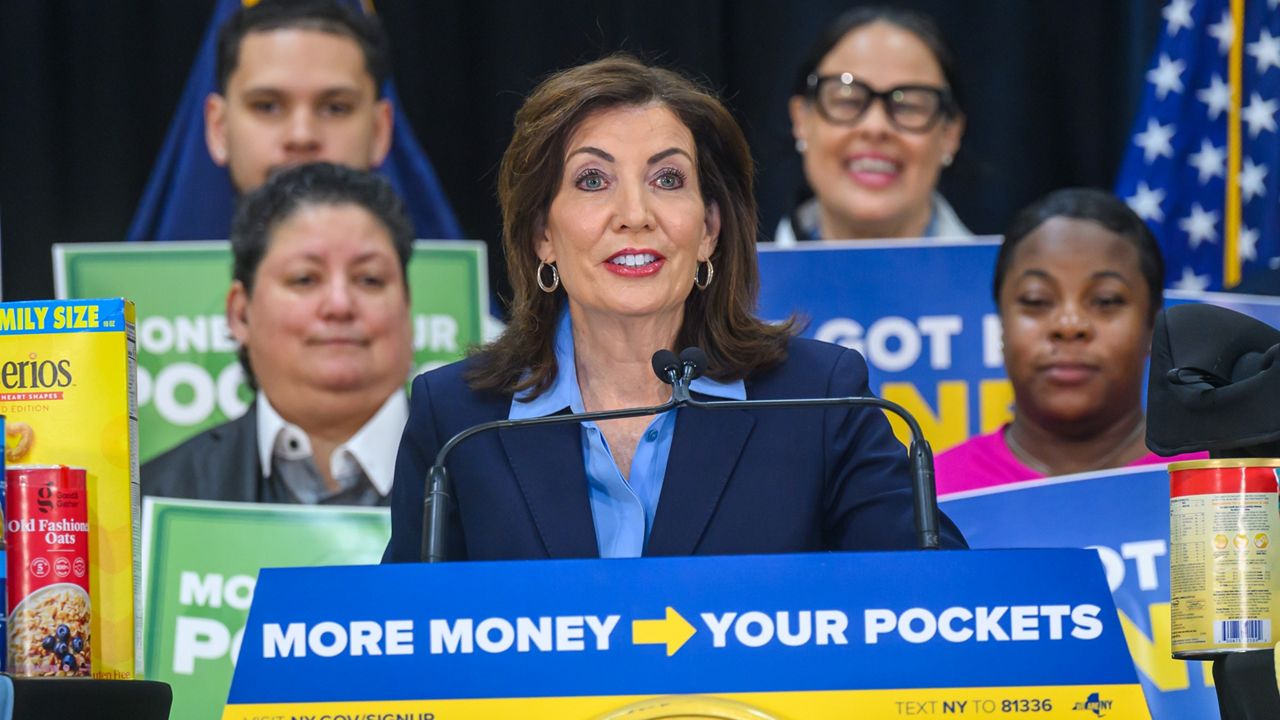

Legislatures in New York and other states have indicated that look-back windows are likely going to remain fixtures of overhauls of statutes of limitations for abuse crimes: In June, New York’s state Senate passed the Adult Survivors Act, which would create another one year look-back window allowing survivors of sexual abuse who were over 18 when the abuse occurred to sue alleged abusers and culpable people and institutions, regardless of when the statute of limitations on the crime ended.

The Assembly did not bring the bill for a floor vote, leaving the future of the bill uncertain.

)