Cars crawling through a foot of water on the Harlem River Drive. Straphangers wading through chest-high pools to get from subway platform to stairway. Water racing down Dyckman Street and pooling along Broadway in Upper Manhattan.

Several inches of rain dropped on parts of New York City Thursday evening, overwhelming the drainage system in those areas, which led to flooding and outflows of sewage into city rivers. Videos on social media chronicled the downpour that left some parts of the city drenched and others entirely untouched.

The cloudburst, as experts call such brief but intense deluges, is one kind of storm that the city can expect to see more of as climate change makes our weather more severe. And while the city has invested billions to update its infrastructure to avoid the resulting flooding, experts say that the city is still not fully prepared for the damage these storms will bring.

“It’s common with these types of storms to have a situation where one neighborhood gets dangerous flooding, while not that far away, no one realizes there's an emergency happening,” said Bernice Rosenzweig, a professor of environmental studies at Sarah Lawrence College and a member of the city’s climate science panel.

Despite the intensity of flooding shown in videos, the city said that the storm caused no damage.

“We checked in with our operations folks. There are not reports of significant damage due to Elsa and the weather we recently experienced,” Christina Farrell, a spokesperson for the city’s Emergency Management department, said in an email.

“Yesterday’s intense storms caused flooding in rural, suburban and urban areas of the metropolitan region - New Jersey, Connecticut and New York City," Ted Timbers, the spokesperson for the city’s Department of Environmental Protection, said in an email. "Particularly hard hit were portions of upper Manhattan and the West Bronx where more than five inches of rain fell - that volume of water in a short time period will overwhelm drainage systems.”

Flooding caused by rainstorms is not new to New York City, Rosenzweig said, but what is new is the increasing frequency, caused by climate change, and the use of phones and social media in spreading videos of such flooding far and wide.

Climate change is making the atmosphere warmer, she said, meaning the air will hold more and more moisture. Longer and more intense hurricane seasons as well will mean more storms of this type.

“With everything else being equal, when you have a rain storm like this, and it’s warmer, it will rain harder,” Rosenzweig said. Cloudbursts typically release enough rain to overwhelm just about any city, not just New York, she added.

Flooding caused by sea level rise — coastal flooding — has been the main focus of both government and residents, especially since Superstorm Sandy caused $60 billion of damage in 2012.

But flooding caused by intense rainfall — pluvial flooding — is a problem that the city is only beginning to fully understand, Rosenzweig said. The rainfall is immensely difficult to forecast, and the city does not have technology to monitor the flooding it causes in real time.

“Most New Yorkers don't understand this problem and the risk that it presents to them, their families and their property,” she said.

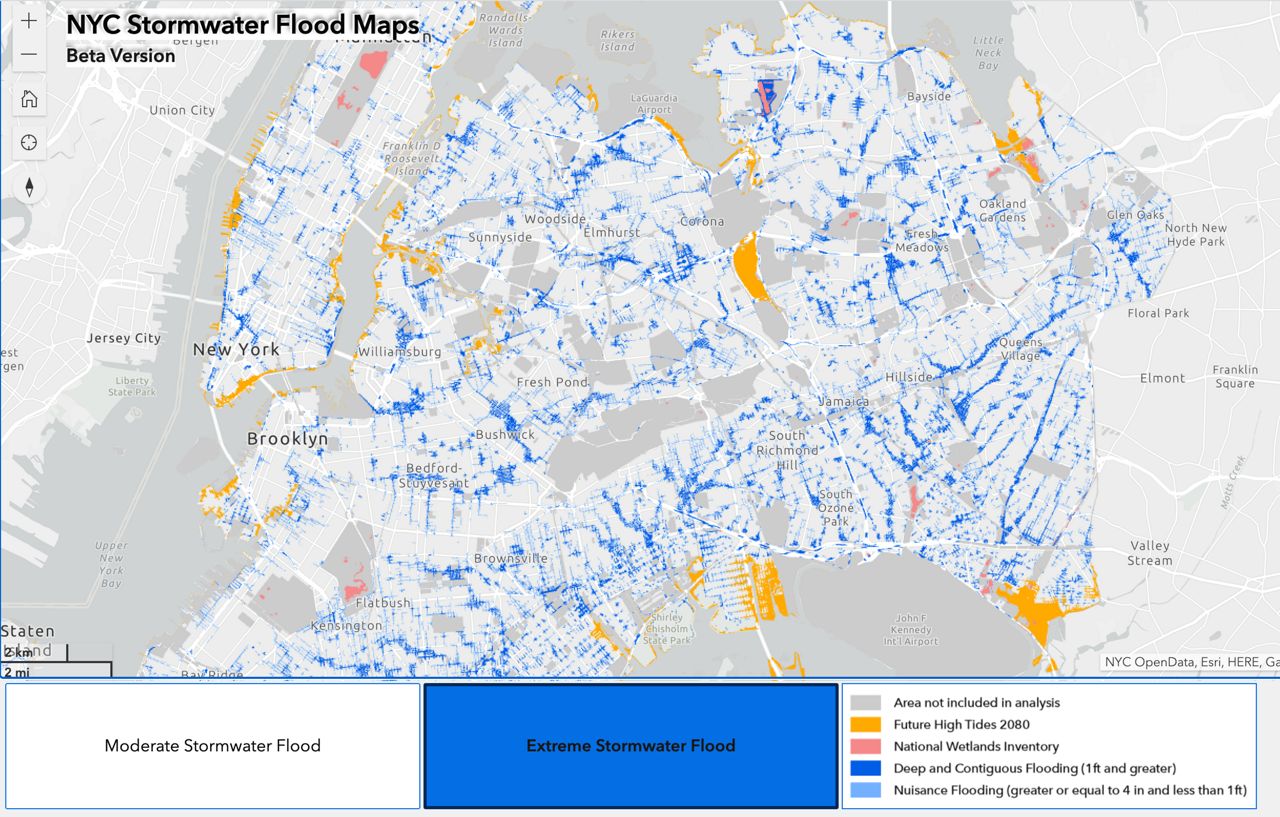

In May, the city released a report on stormwater resiliency which noted that the city could experience 25% more rainfall by the end of the century.

A map included with the report showed how stark the risk is for communities across the city. The “extreme stormwater flooding” scenario, representing a projected 3.5 inches of rain in one hour, combined with expected sea level rise, shows blue flood zones across nearly all of Queens, the northeast Bronx, south Brooklyn and the beachside neighborhoods of Staten Island.

The map is the result of the first modeling effort for inland flooding for the city, the report said, prompted by the enactment in 2018 of Local Law 172, which requires the city to update the maps every four years.

One major problem the city is facing with flooding is that about three-fifths of its sewage system is combined, meaning that the pipes carry both sewage and rainwater. When there is excess rainwater, sewage gets washed into New York City waterways. The overflows are typically made up of 10% wastewater, Timbers said.

Yet that amount adds up to billions of gallons of polluted stormwater dumped into city waters each year, and it doesn’t include the other chemicals that the water picks up as it makes its way through the street and subway system.

“If there are certain locations that are flooded that have industrial contaminants, those get mobilized as well,” said Andrea Silverman, an assistant professor of environmental engineering at New York University. “It’s like a disgusting, toxic soup, potentially.”

The city has invested more than $16 billion in recent years to upgrade the sewer system, improve rain catchment and make sure sewage doesn’t leach into city waterways, resulting in the cleanest water in more than a century, Timbers said.

The city is also continuing the separation of rainwater and sewage pipes “where feasible,” Timbers said, including in the Gowanus, Canarsie and College Point areas.

The May report on stormwater flooding also noted that the city has reduced the volume of combined rain-and-sewage runoff by 80% since the 1960s, helped in large part by major reductions in citywide water usage.

Yet sewage runoff caused by repeated pluvial flooding poses a threat to that progress, Rosenzweig said.

“The green infrastructure that's being broadly implemented is being designed for frequently occurring events under our current climate. And our climate is simply going to change,” she said. “That means more overflow events, and we’re going to roll back a lot of the progress that we've made in terms of our water quality.”

Silverman and fellow NYU engineering assistant professor Elizabeth Hénaff are working on a project to help the city figure out where its needs are greatest in updating infrastructure by creating sensors to install across the city that will monitor flooding in real time.

“There’s no rigorously collected, quantitative data about the nature, frequency and extent of these events,” Hénaff said.

So far, she said, the data reveals just how hyperlocal the floods can be: The project’s pilot areas, around the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn and in Queens’ Hamilton Beach neighborhood, on Jamaica Bay, didn’t register any flooding Thursday night.

Yet that shouldn’t reduce anyone’s level of alarm, Hénaff said.

“The sense of urgency is real. But it’s been real for a while,” she said. “What these kinds of drastic, almost violent events do is really bring it to the forefront as far as the impacts of this kind of flooding.”