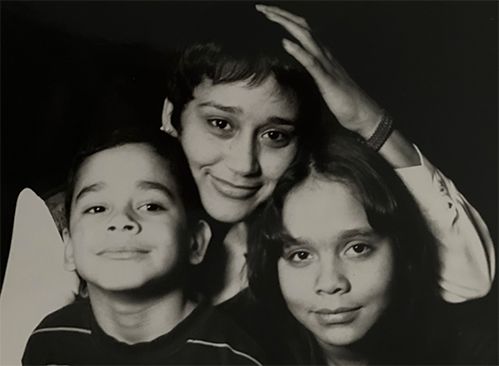

Before Valerie Reyes-Jimenez learned she was HIV-positive, she had to plead with nurses to give her the test.

It was February 1989 and she had been living in Puerto Rico for about a year when she went to a local clinic.

She was experiencing constant yeast infections and severe skin rashes.

“I asked the nurses, ‘Can you test me for this HIV thing?’” said Reyes-Jimenez. “And they looked at me like I had three heads.”

At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, it was largely considered a gay white man’s disease.

Though women represented the fastest growing group of adults with AIDS by the 1990s, the experiences of African American and Latina women — who were disproportionately affected — were largely ignored and they were left out of drug trials and advocacy campaigns.

That is why Reyes-Jimenez, 56, who was born and raised on the Lower East Side, says she had such a difficult time getting tested.

She was married at the time with two kids. Her husband had a history of intravenous drug use, but had never been tested for the virus.

“Most of the women who we serve contracted HIV through heterosexual transmission — not through sex work and not through drug use, but many of them in committed relationships when they contracted HIV,” said Ingrid Floyd, executive director of Iris House, a Harlem-based organization serving women and families with HIV/AIDS.

As antiretrovirals improve over time, this first generation of HIV/AIDS survivors is entering its 50s and beyond.

In New York City, 59% of all people living with HIV and AIDS were over the age of 50 in 2019 and the percentage increases by about 1.5% each year, according to officials from the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, an AIDS services organization.

For women of color who are aging with the virus, the stigma is something they often need to contend with over time.

“Because the stigma in our communities still exists, places like Iris House are still for some of them the only place that they can talk about their HIV status,” Floyd said.

When Cynthia Taylor Green was diagnosed with AIDS, she was burdened with the uphill battle of educating her loved ones.

She often shared a cigarette with her son before or after work, but that changed shortly after she told him of her diagnosis.

“I said, ‘Well, do you want some of this cigarette?'" said Taylor Green, 67. “He said, ‘Nah, that’s all right. I'm good.’”

It wasn’t long after that she noticed he moved all of his belongings out of the home they shared.

“That was a shocker,” she said. “I was like, ‘You weren't going to tell me you were gonna move?’”

He wouldn’t admit to the reason for his sudden change in behavior, she said.

“But I knew what it was,” said Taylor Green, who grew up in Washington Heights. “It's because I was diagnosed with AIDS. He thought, ‘Well, I'm a catch it if I stay here.’ I had to educate him and tell him that is not how you catch HIV and AIDS.”

And as these women get older, the cycle of disclosure and education continues.

“In our client population, a lot of women who are HIV-positive are mothers again,” Floyd said. “Even though they’re grandmothers —they are raising kids again.”

As survivors age and potentially stay in the dating scene longer, the issue of disclosure arises.

Taylor Green remembers disclosing her HIV status to a man she was dating at one point and described his reaction as “cold-hearted.”

“I went to hug him and I got a cold feeling, a chill that just went over me because it wasn't a true hug like he usually gave me,” she said.

The ramifications from long-term use of antiretrovirals is an area still vastly understudied, according to advocates.

And though medications have improved, women who are long-term survivors can recall periods where they had to take dozens of pills a day or, when they were finally included in drug trials, taking medications they describe as “vile.”

“There was one — something happened to the pills that they started to crystallize so they had to give everybody the liquid version,” Reyes-Jimenez said. “I wanted to gag.”

Some say they take “cocktail holidays” just to get a reprieve from the regimen of heavy medications.

Raven Lopez, who was born HIV-positive, recalls taking “holidays” as a teenager because she was tired of the stigmatization she faced bringing all of her medications to school. But there were consequences.

“Every time I did that, I built resistance to my medication so [my doctor] had to always switch me,” said Lopez, 31. “And then when he switched me out, it was a new side effect — either diarrhea or I'd break out in hives.”

Survivors say a big part of aging with HIV means becoming your own health advocate.

People living with HIV and AIDS often have to see multiple doctors to manage their care and to try and find out what’s causing certain ailments.

“People who are long-term survivors have to try to discern: is this a result of long-term use of HIV antiretrovirals or is it just aging?” Floyd said.

For instance, Reyes-Jimenez has a strong suspicion about where the neuropathy in her legs comes from.

“I honestly truly believe that they're directly as a result of the HIV meds,” she said.

Michelle Lopez works at the Gay Men’s Health Crisis counseling on the issue of aging with the virus and sees this issue come up often.

“The older population, seeing unknown manifestations of clinical stuff,” she said. “Why all of a sudden now I'm having this bad diarrhea? Or my GI tract is f— up and I don't know why.”

Survivors like Reyes-Jimenez say her generation has to be pioneers even if it means constant research and advocacy.

“I like the way the air feels going down my lungs,” she said. “I like breathing and I'm gonna continue to fight so I can breathe as long as I can.”