It’s been 36 years since Eric Sawyer was told by his doctor that he had two years left to live.

It was 1985, and his boyfriend Scott was dying of AIDS.

The trauma of that time is why his doctor initially withheld that life sentence when Sawyer first found out he was HIV-positive years earlier.

“The doctor said, ‘I didn't want to let you know that Scott literally had less than a year to live at that point, but you have probably less than two years to live so you should get your affairs in order,'” said Sawyer.

But at 67 years old, he’s still standing and credits his survival to a friend who helped connect him to the right doctors at the time.

Much was unknown about the disease back then, making proper treatment that much more difficult. And in New York City, where Sawyer lived, people were dying at an alarming rate.

“I probably would have died much, much earlier,” Sawyer said.

More than 116,000 people have died of AIDS in New York since the beginning of the epidemic, according to city data.

And disparities in access to life-saving medications for marginalized communities are still stark.

Black people account for a higher proportion of new HIV diagnoses than other racial and ethnic groups, according to the Centers for Disease Control. And Black/African American gay and bisexual men had the highest number of new HIV diagnoses, according to a 2018 analysis.

“Access is the key word,” said Sarah Schulman, author of “Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993.” “And because we do not have a logical and coherent health care system in this country, there are people who cannot access the drugs that do exist.”

This month marks the 40th anniversary since the first five cases of what later became known as AIDS were officially reported in the United States.

And though treatment options are now available that enable people who are HIV-positive to lead long lives, activists early on in the epidemic had to fight tooth and nail for basic rights, such as having compassionate doctors.

The friend of Sawyer’s who connected him to such doctors was Larry Kramer, the pioneering AIDS activist and writer and co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power).

These two organizations would eventually help alter the landscape of services and rights for HIV-positive people in New York City and around the world.

Sawyer considers himself one of the lucky ones.

“Having access to some of the few doctors that were treating AIDS patients, I was kept healthy enough to survive until the triple cocktail became available,” said Sawyer, referencing one of the first combination antiretroviral medications, Indinavir, which became available in 1996.

When Sawyer heard the two-year life sentence from his doctor, the U.S. death toll from HIV/AIDS was 16,458, with New York City at the epicenter.

Despite the critical need for aid, government officials, scientists and researchers were largely slow to react and enact change.

Many people at that time felt that because the groups most affected by the disease — gay men, drug users, sex workers and other marginalized groups — the general public was apathetic about the massive loss of life, advocates said.

“There was not enough space for people with AIDS,” said Schulman. “The epidemic was so big. Many people died on gurneys in hospital hallways in New York.”

Not only was there an urgent need for basic care, there was also a huge vacuum of information.

That is why physician Larry Mass, along with five others — Nathan Fain, Paul Popham, Paul Rapoport, and Edmund White — gathered in Larry Kramer’s apartment one Monday in the summer of 1981 to eventually create the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, an AIDS service organization, which continues to serve New Yorkers today.

“People needed a hotline where they could call in, like, ‘I've got these purple spots. I'm coughing. Where do I go? What do I do? Will they see me at this hospital or that clinic? Are there certain doctors I should go to?’” Mass said.

For Mass, the information component was the significant motivating factor for him.

“I felt like as a physician, it was up to me to do everything I could to kind of really stick to the facts and not get too crazy with panic,” he said. “I had a strong sense of the danger of fanaticism, of denialism, of conspiracy theories. Early on, there was talk about chemical biological warfare, which didn't seem so crazy at that time because we were an undesirable marginal community.”

Some of the services GMHC provided in the early days of its inception included the creation of an AIDS hotline and a “buddy” program to assist people with their daily needs, such as grocery shopping.

“In those five years, the gay community mostly focused on recreating the kind of social services that we should have had, if we had been recognized and if we had had family support, which many people did not have,” Schulman said.

But Kramer, who died in 2020, wanted the service organization to go even further.

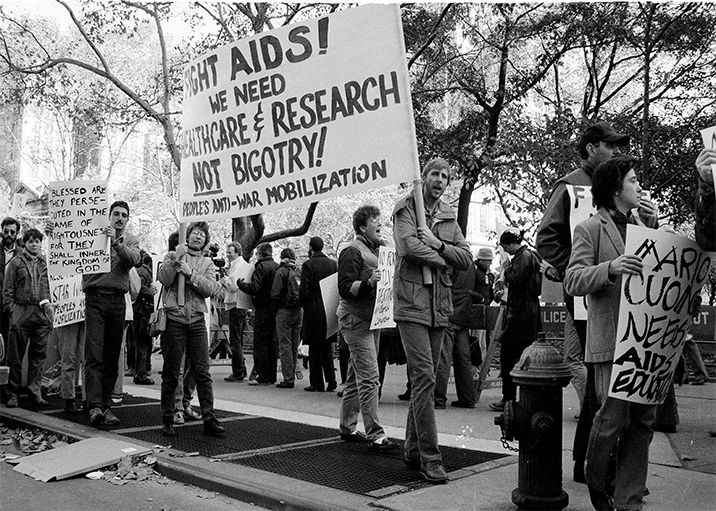

He continued to advocate and eventually formed ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power), the groundbreaking direct action organization.

“Larry felt very strongly we needed to sound all the alarms — we needed to sound them as loudly as possible,” Mass said. “What good are civil liberties if we're all dead? That was really the perspective.”

Sawyer was one of about a dozen people Kramer asked to attend his now famous speech in 1987 at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in Manhattan, which launched the defiant coalition.

“When Larry gave the call to arms, we stood up, we volunteered, we made statements about how outraged we were that nothing was happening to save our lovers, our own lives and that we would join him in that effort,” Sawyer said. “Planning began immediately the next day at Larry's apartment on Fifth Avenue and Washington Square Park.”

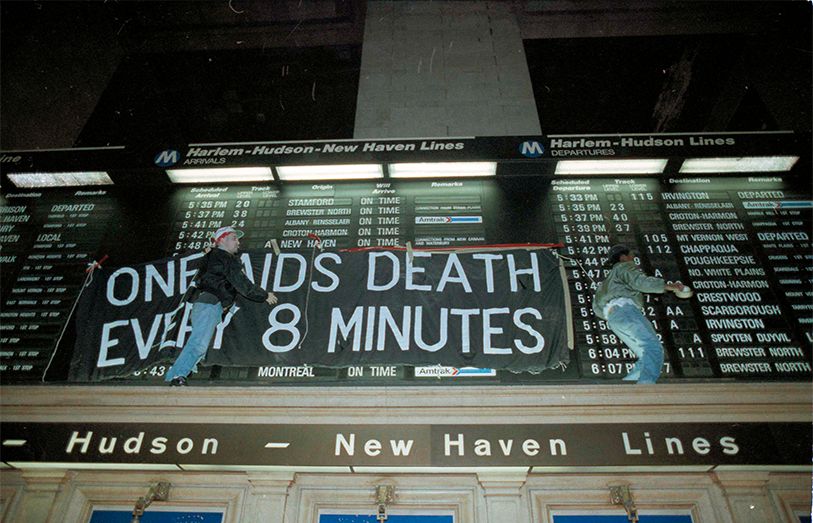

The group shortly organized a demonstration in front of Trinity Church at Wall Street and Broadway, stopping morning rush hour traffic, he said.

“The fact that gay men primarily living with AIDS and their supporters were doing civil disobedience and getting arrested while blocking traffic in front of Wall Street while sticking their fingers at the drug companies and the government for not trying to find treatments — it got a lot of press,” he said.

Sawyer said the inaction of the government and general public is what drove him and so many others to organize at this time.

“We were also really furious about the stigma, the misinformation and the outright abuse that people with AIDS were facing,” he said. “People with AIDS were evicted from their apartments, fired from their jobs, you know, basically disowned by their families. Many people with AIDS ended up living on the streets because they lost their apartment, lost their jobs or were thrown out by their loved ones or family members.”

Sawyer eventually founded Housing Works, a nonprofit addressing AIDS and homelessness.

“When we couldn't get the government to develop medically appropriate housing and when we couldn't get housing organizations to allow AIDS patients to live there or when we couldn't get AIDS organizations to take on the added burden of providing housing, we decided, ‘Well, if anybody's going to do it, it's going to have to be us,’” Sawyer said of the organization, which started as an ACT UP committee.

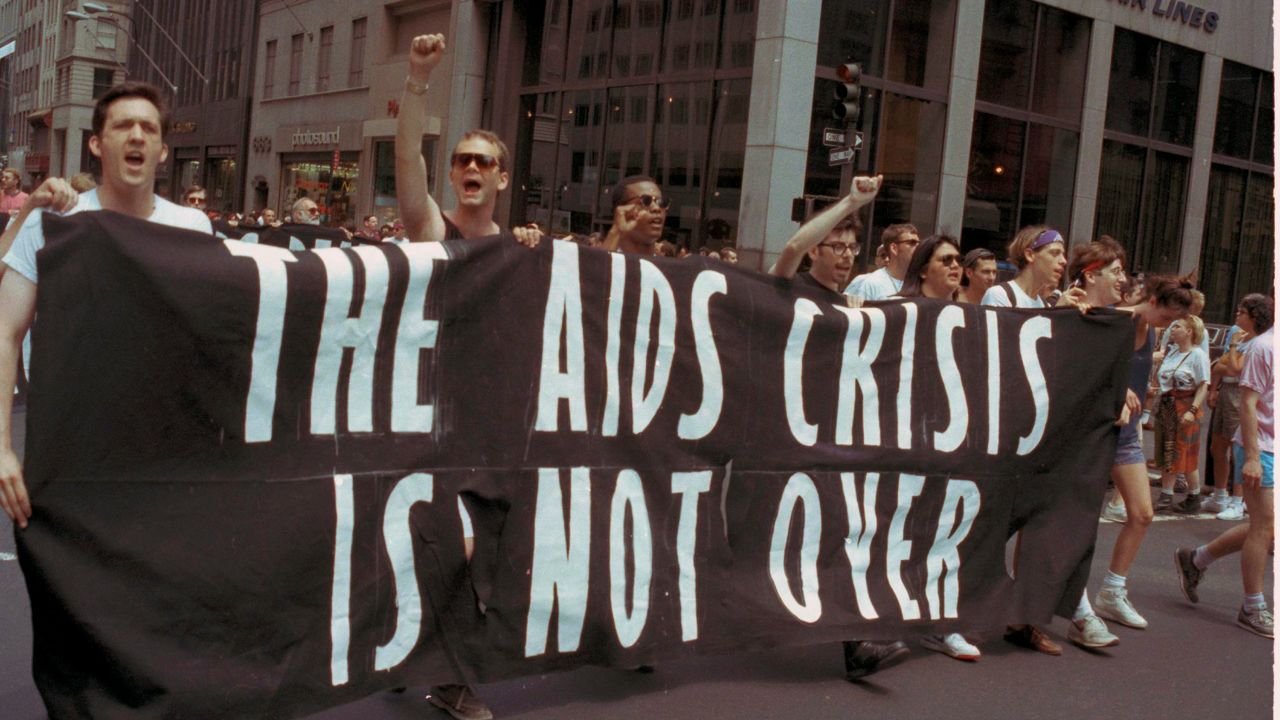

ACT UP revolutionized patient care and drug research and laid the model for organizing for years to come.

Forty years after the AIDS epidemic began, this history of organizing is something that Schulman and others want to ensure is not forgotten today.

“We're in a moment of crisis in this country when many people want profound structural change,” Schulman said. “And one of the hardest things to access are the tactical and strategic details of earlier movements. That information is very hard to get and ACT UP was one of the few social movements that actually was successful.”

Among ACT UP’s achievements: A fast-track system for sick people to access unapproved experimental drugs; legalized needle exchange in NYC; ending insurance exclusion for people with AIDS; and running a four-year campaign to change the Centers for Disease Control’s definition of AIDS so that women could get access to benefits and be included in experimental drug trials.

Despite these achievements, including the advancement of antiretroviral medications, many believe there’s still plenty of work to be done.

“People can live normal, good lives, thanks to these medications and thanks to the work of the ACT UP activists who played such a key role in this happening, but we still don't have a cure, nor do we have a preventive vaccine,” Mass said.

In 2020, there were 690,000 AIDS-related deaths worldwide and 1.5 million people were infected with HIV, according to UNAIDS.

“We have to remain ever vigilant about this and remaining ever vigilant means we may have to do what Larry [Kramer] did,” Mass said. “He made a lot of noise and pissed off a lot of people. But he learned it was very effective and persuasive in demonstrating that that was what was needed. Those lessons are ones that are before us now, and we may have to re-engage with them.”

_Pkg_Wash_Heights_Mourns_DR_Roof_CG_133997101_58)