Sue Pugliese’s daughter, Michelle, loves to give out hugs. At her school on Staten Island, this doesn’t normally cause any issues. But now, that simple act could potentially escalate to serious punitive measures. It’s a fear her mother has with the new guidelines in place in schools across New York City as students returned this week for in-person learning.

“She’s going to go to school and you're not gonna let her hug you?” Pugliese wondered about her 19-year-old daughter with autism spectrum disorder. “She'll have fits and they’ll be calling 911 on her daily.”

It’s the change in routine that can be most upsetting for special needs students.

Dawn Vollaro’s son, Dylan, started school this week and the biggest issue came during lunchtime.

“He could not eat in the lunchroom and that really threw him off,” Vollaro said of her third-grade son. “They got a battle out of him.”

It’s not just the new rules around social distancing or mask wearing that can throw special needs students off. It’s the whole schedule currently in place called blended learning, where students alternate weekly between in-person and remote instruction.

“Our kids need a routine,” said Pugliese, who has another daughter, Josephine, with autism spectrum disorder as well. “Five days on and five days off will kill these kids.”

New York City is the biggest school system in the country to attempt a return to in-person learning this fall. District 75, which serves 25,000 students with the most complex disabilities, opened its doors on Monday. There are about 200,000 students with disabilities across the city, which means if the special education population were its own district, it would be one of the top ten biggest nationwide.

And while there have been setbacks and frustrations across the entire school system with re-opening, the concerns for special needs students, their parents and teachers are particularly acute.

The parents of special education students say their main issue is around the blended learning model. This alternating system was put in place to accommodate social distancing requirements with limited facility space, according to the Department of Education. It also allows class sizes to be cut in half.

The only options parents had were full-time remote or blended learning.

“I wish that parents had a real choice,” said Vollaro. “Blended learning is no choice whatsoever. It is a logistical nightmare and it's not working. It's a true failure.”

Not only do parents have to find childcare for the weeks that students are remote, but there’s also the issue of whether remote learning works at all for special needs students.

Sue Pugliese’s two daughters, Josephine and Michelle, will either turn off the computer or flat-out refuse to take part in remote learning. In one instance, Pugliese says she was on the computer with her daughter, her teacher, therapist and paraprofessional. Josephine did not want to be on the computer.

“She went ballistic, and she started beating me,” Pugliese said. “The teacher, the paraprofessional and the occupational therapist were yelling, waving their hands, saying, ‘Stop, stop.’ Are you kidding me? I barely heard them. You think she's gonna hear it over beating me?”

Parents also fear their children are regressing -- both academically and behaviorally -- with the missed classroom time since the shutdown began in March.

“I just did the very minimal,” said Vollaro, who balances raising her son with her job teaching high school math in Manhattan. “I just did his therapies. He got nowhere in terms of advancing math skills, science skills, English, social studies—none of that. That was a wash.”

Special needs students also require a range of services including occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech therapy, counseling and more. Parents say many of these services, particularly physical therapy, are nearly impossible to do remotely.

“One of my daughters now has echolalia,” said Pugliese. “She's starting to repeat every single thing that everybody says. And she's never done that. It’s because she’s not having conversations at school with people.”

That type of regression isn’t as easy to address for special needs students as it might be for their more neurotypical classmates.

“The danger of falling behind with each day of lost services is amplified for special needs students,” said Maggie Moroff, special education policy coordinator for Advocates for Children of New York. “It’s almost exponential. A lot of the skills the students are working on are building systematically so time away is really problematic.”

Despite the unique needs of special education classrooms, many teachers felt like there wasn’t enough guidance from the top on how to handle this new environment.

“Sometimes a child might not understand physical boundaries,” said Deirdre Levy, a K-2 special education teacher at P.S. 9. “You can get in very close proximity to a student. For special education teachers, [reopening] is especially risky.”

Several dozen teachers, paraprofessionals and teacher delegates signed a letter addressed to the mayor, the chancellor and governor on August 31, saying there was not enough direction regarding their students’ needs.

“As District 75 students and staff, we needed something that was more detailed,” said Sarina-Ann Raffa, a paraprofessional at 811Q and one of the letter’s co-authors, about the Department of Education’s reopening guidelines. “We need different types of PPE, different types of training, and other safety precautions, and we were totally getting ignored.”

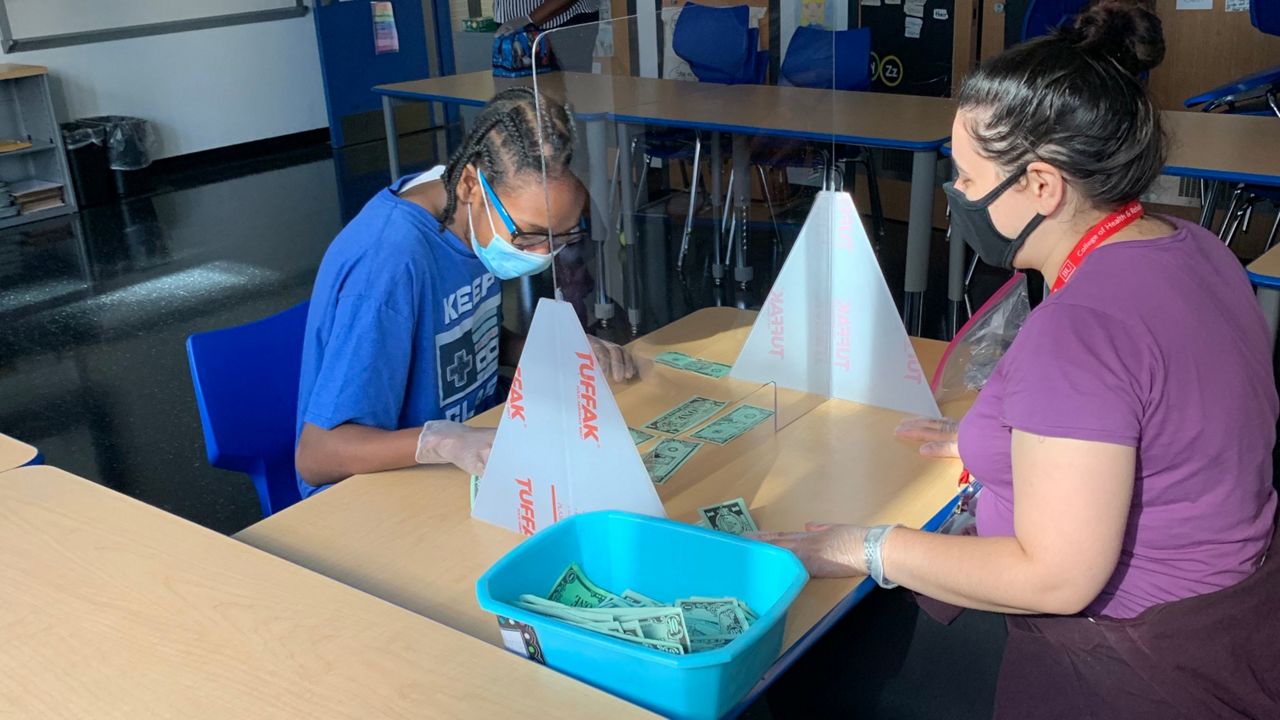

For example, while teachers across the school system complained about the lack of basic PPE provided to them, special education teachers were also waiting on extra gear like face shields, gowns with sleeves and gloves. That type of protection would help in situations like when a student like Michelle tries to hug them.

“We would prompt her to shake our hand or give us a high five, and we would be wearing gloves, of course,” said Raffa.

The Department of Education says the letter spurred it to strengthen communication with the teachers union and adapt the protocols to meet the requirements of special needs classrooms.

A response was sent to all of District 75, detailing PPE supply information and health and safety protocols for mask-resistant students. Some of the tactics included allowing students to wear a mask for short periods of time to build up tolerance, allowing choice in the type of fabrics that masks are made of, and using social storytelling and visual cues to reinforce the importance of masks.

For teachers like Deirdre Levy at P.S. 9, it means relying on the skills and experience she’s developed over the years in special education.

“I’m trying to be innovative and creative, so I can meet the needs of every learner in my classroom,” she said. “If I have to livestream a whole group instruction, then I will because I want to make sure my students have access to me and to the classroom setting even if they're not in the classroom. It’s this ongoing Tetris battle of trying to plan out how to make sure every kid gets their access.”

While nearly everyone agrees that full-time in-person learning is the best option for special needs students, how exactly that can be carried out during this pandemic remains a frustration and source of disagreement between all parties involved.

But it doesn’t stop children across the city from the excitement of returning to the classroom— whatever that looks like.

“There's so many children that went to school. Normally, they would go kicking and screaming and crying,” said Pugliese. “But now they get home, and they’re asking for school again.”

An earlier version of this article misstated the sisters' names. Michelle is the 19-year-old and her sister's name is Josephine.

An earlier version of this article misstated the borough where Dawn Vollaro works. She works in Manhattan, not on Staten Island.

An earlier version misstated Sarina-Ann Raffa’s position. She’s a NYC DOE paraprofessional, not a teacher.