Add another New York City mayor to the Democratic field for president.

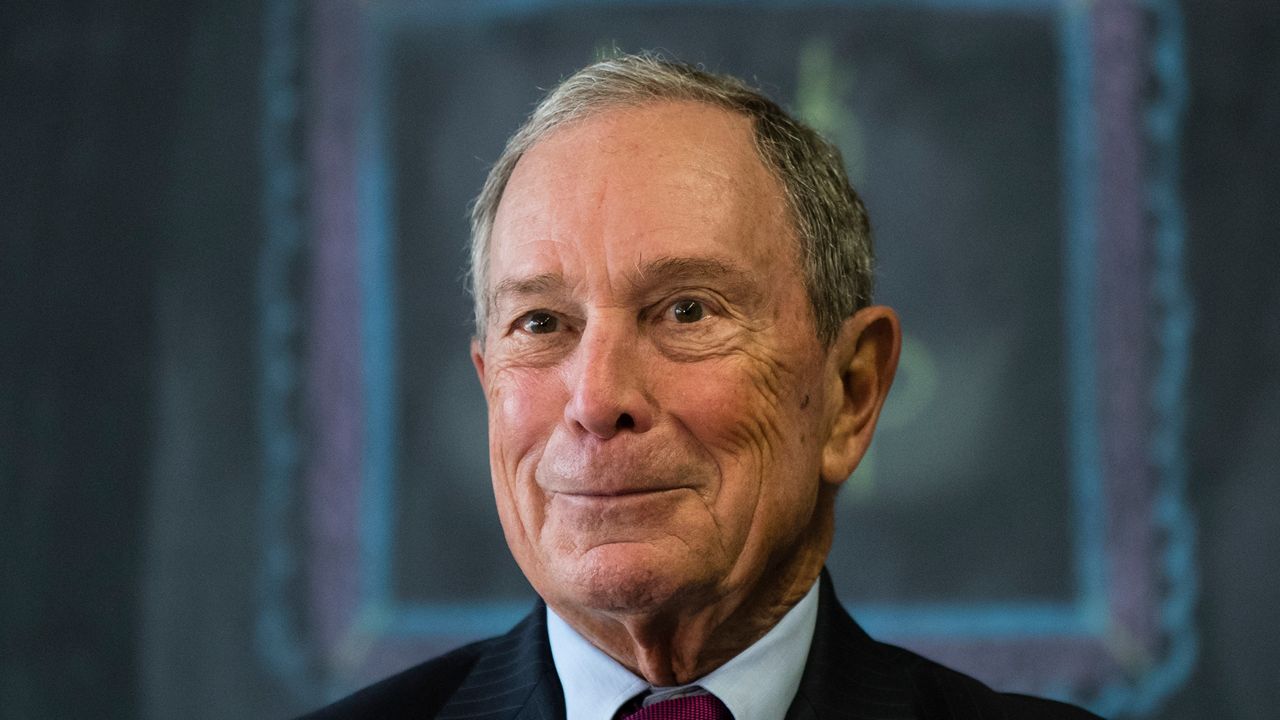

Less than a year after saying he would not make a 2020 bid, former Mayor Michael Bloomberg is joining the crowded field. He announced his candidacy Sunday in a written statement posted on a campaign website.

"I am running to defeat Donald Trump and rebuild America. I believe my unique set of experiences in business, government, and philanthropy will enable me to win and lead," Bloomberg said on Twitter.

His campaign launch video cites his accomplishments at City Hall and in business.

Like in his mayoral campaigns, Bloomberg is not going to take any political donations. Instead, he will use his vast personal fortune to make his case to the American people. That could block him from the debate stage, where candidates must receive thousands of donations to qualify.

Bloomberg, who served three terms, from 2002 to 2013 as the 108th mayor of New York City, joins a field that features more than 15 Democratic candidates aiming to unseat President Donald Trump.

In early March, after months of speculation, Bloomberg said he wouldn't aim for the White House, citing the difficulties he expected if he joined the large field. The Democratic field has winnowed only slightly since then, with fellow New Yorkers Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and current mayor Bill de Blasio dropping out.

In an op-ed released on the Bloomberg website earlier this year, the former mayor had said he believed he would beat Trump in a general election but added that he was "clear-eyed about the difficulty of winning the Democratic nomination in such a crowded field."

Bloomberg also said in the op-ed that, until 2021, "our only real hope for progress lies outside of Washington."

"I've come to realize that I'm less interested in talking than doing. And I have concluded that, for now, the best way for me to help our country is by rolling up my sleeves and continuing to get work done," Bloomberg said in the op-ed.

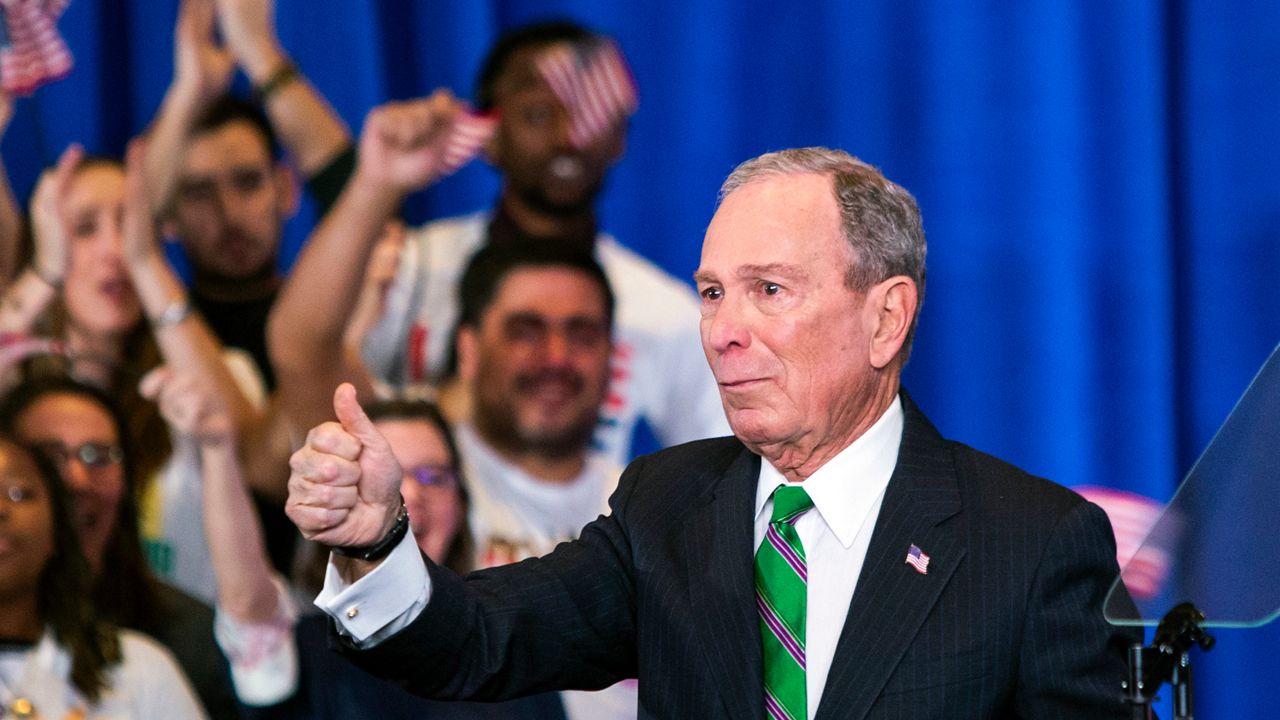

But the billionaire recently began backtracking, moving to appear on the ballot in multiple primaries in order to meet some early filing deadlines and seemingly to give himself options in case he ran. He also committed to spending $100 million on anti-Trump digital ads in the swing states of Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Trump, whose campaign has spent significant cash online for his re-election bid, narrowly won the four states in the 2016 general election. And he is spending over $30 million on campaign ads that will hit dozens of states this week, the largest single-week ad buy by a candidate ever.

A CENTRIST ON THE ISSUES

In early November, when news broke that Bloomberg was again considering a run, adviser Howard Wolfson said the former mayor was worried that the current crop of Democrats was "not well positioned" to defeat Trump. Bloomberg reportedly has feared that many candidates are too far to the left, and that former Vice President Joe Biden, more moderate than most Democrats running, has shown political vulnerabilities and hasn't broken away with the lead in the polls.

Unlike most of the Democratic presidential candidates, who tout their chops as liberal and progressive, Bloomberg is more of a political centrist:

Climate change regulations: Supports them, but he is skeptical of the "Green New Deal." He argues the United States cannot afford it and the legislation will never become law.

Wealth tax: Against it, saying it would be unconstitutional. The exact number isn't clear, but Bloomberg could stand to lose a chunk of his $52 billion fortune due to a wealth tax, which Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren has espoused. However, in his campaign launch video Sunday, Bloomberg said he will make sure the wealthy pay more in taxes. It's unclear how much he wants them to pay.

Single-payer health care: Against a "Medicare for All" plan that would replace private insurance with a government-run program, saying the U.S. cannot afford it.

Gun control: Supports universal background checks, a ban on assault weapons, and "Red Flag Laws." The former mayor helped found Everytown for Gun Safety, which advocates for gun control across the nation. He does not, however, support a mandatory buyback program for assault weapons, calling it impractical and telling Margaret Hoover of PBS that it would be a rallying cry for gun rights' supporters.

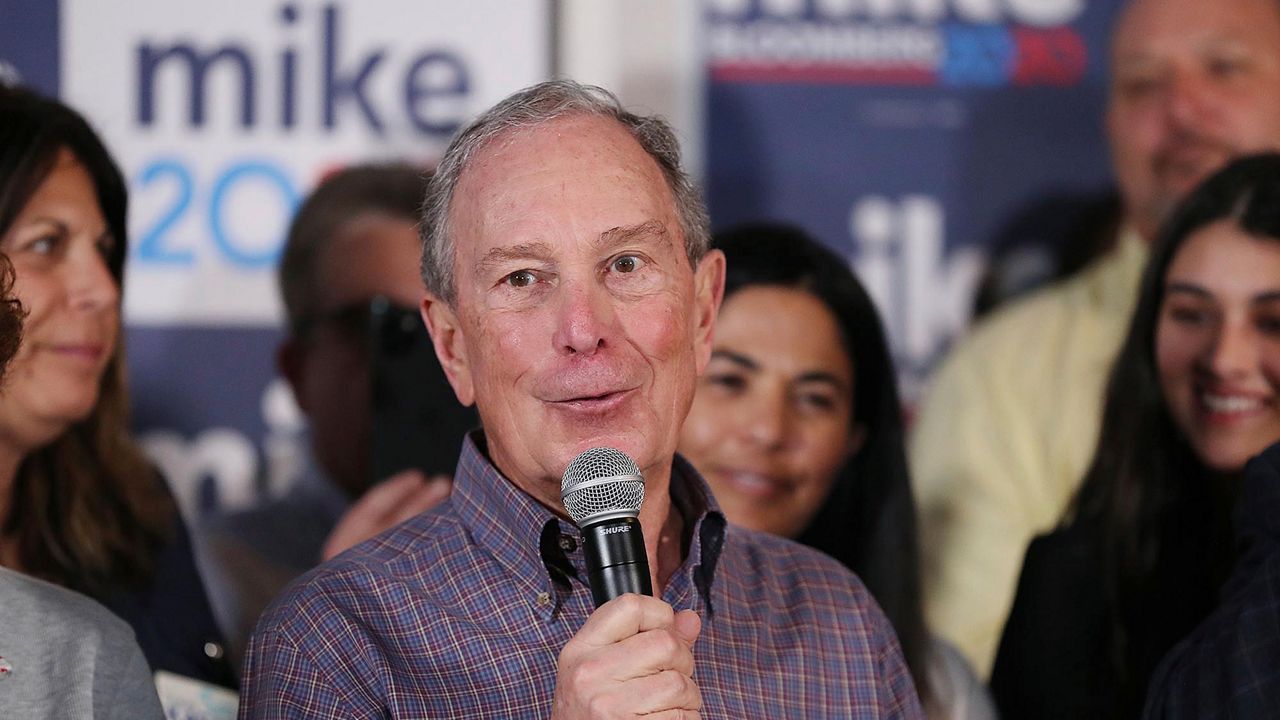

Bloomberg — who will likely argue his centrist positions make him best suited to defeat Trump in the general election campaign, for which candidates historically have moved closer to the center — reportedly may skip the first four Democratic nominating contests:

- Iowa caucuses (February 3)

- New Hampshire primary (February 11)

- Nevada caucuses (February 22)

- South Carolina primary (February 29)

Instead, he could aim for Super Tuesday (March 3), the name for the large number of state contests that day.

There is no filing requirement for a candidate to run in the Iowa caucuses, which are a series of Democratic Party meetings, not state-run elections. It means a candidate can enter the race for the February 3 leadoff contest at any time.

But Bloomberg now needs to swiftly make up ground to compete with candidates like Biden, Warren, and others, who have spent months traveling the country meeting voters. In addition, he's not made much traction among voters, polling in the single-digits with a net favorability rating of 6 percent, according to a November 10 Morning Consult poll; his opponents have had much of 2019 to build out extensive teams of staffers on the ground; and no candidate has ever won a modern primary after entering the race so late. According to FiveThirtyEight, since 1976, no eventual president nominee (excluding incumbent presidents) has ever launched their campaign with less than a year to go before the general election. Bloomberg's hoping to smash that streak.

RECORD IN NEW YORK CITY

Bloomberg was elected to three terms as New York City mayor — twice as a Republican in 2001 and 2005, and as an independent for his third term in 2009.

His record during that time will almost certainly be a frequent point of discussion. He earned praise for the city's crime rate continuing to fall under his watch, and some Democrats have supported his focus on public health, such as banning smoking in bars, restaurants, parks, and other public spaces.

But his record in New York has also drawn the ire of his party. For years, until this November, Bloomberg defended his support of stop-and-frisk while mayor:

The NYPD's stop-and-frisk policy involves police temporarily detaining someone and checking them for weapons or anything else illegal. Critics of the policy charge it often amounts to racial profiling, with a disproportionate number of minorities stopped for the searches.

As soon as Bloomberg took office in 2002, the number of stops by the NYPD skyrocketed, climbing to its highest point in 2011: 685,724.

Stop-and-frisk incidents began to decrease as a class action lawsuit against the practice made its way through court. In 2013, a judge ruled the practices were unconstitutional and discriminatory.

Bloomberg's reversal, six years after the ruling, made headlines for a man not known for admitting errors. In fact, he defended the policy just this past January. Critics panned his apology as conveniently timed given that he was expected to launch a presidential bid as Democrat, a party increasingly rejecting more aggressive policing tactics.

While his successor has been hammered for the city's homeless shelter population soaring to a record-high of over 60,000 in January 2019, Bloomberg was not able to escape reproach for the count during his 12 years in City Hall, either. According to the Coalition for the Homeless, over 48,000 people were in city shelters by the time Bloomberg left office, an increase over 15,000 compared to January 2002, when he began his first term.

Bloomberg compounded advocates' fury with him in February 2013, when he said "nobody is sleeping on the streets." In fact, by the city's own count, more than 3,200 homeless people were on the streets in January 2012.

The then-mayor's comment came at a time of intense scrutiny over the city's homeless policies. A week earlier, a state appellate court sided with the City Council in its challenge to a Bloomberg administration policy that required single adults to prove they had no other alternative when seeking access to a homeless shelter. City Hall also faced criticism for turning families away from shelters on cold winter nights.

"We're trying to do what we're supposed to do: make sure that people who need services get those services, and that people who don't need them don't get them," Bloomberg said.

MONTHS OF SPECULATION

In some ways, Bloomberg's run was a long time coming. He had teased a White House bid every four years. First, there was the 2008 cycle, when then-Mayor Bloomberg left the Republican Party, fueling speculation he would run for president as an independent. He ultimately took a pass.

"I've thought long and hard, it's been very flattering," he said at the time.

A similar sequence played out in 2012 and 2016, when Bloomberg determined he had no path to victory and could in fact throw the race to Trump.

But the billionaire had been fueling speculation for a 2020 run. In October 2018, he seemingly decided his best shot at winning was as a Democrat, re-registering with the party, arguing Democrats "provide the checks and balance our nation so badly needs." He also poured $110 million into U.S. House of Representatives races on behalf of Democrats.

Bloomberg was also barnstorming the country, including a December trip to Iowa, home to the first-in-the-nation nominating contest. Ostensibly, he was there to promote a new climate change documentary he helped fund. But he also attended events focused on renewable energy that had the feel of campaign stops, and had private meetings with top Iowa Democrats.

In interviews, he seemed to be rehearsing his pitch to voters: "I have a lot of experience which would be useful if I was president of the United States. That doesn't mean I'm going to run."

But there was no secret he was seriously considering it. Bloomberg, who premiered the documentary in Manhattan, was even thinking ahead to what might become of his business, Bloomberg L.P., telling an interviewer he'd likely sell or put the business into a blind trust if he won the White House.

Bloomberg said he would decide by February, but his team had been looking at possible campaign office spaces in Manhattan, according to a source. The source told NY1 in late-February that Bloomberg's advisers were considering the former New York Times building on West 43rd Street and 7 World Trade Center as possible options.

It's unclear if those plans are back on now that he's finally running.

------

Looking for an easy way to learn about the issues affecting New York City?

Listen to our "Off Topic/On Politics" podcast: Apple Podcasts | Google Play | Spotify | iHeartRadio | Stitcher | RSS