Much of the advancements made in mental health care treatments, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder, have been accomplished through the demand for better care for the nation’s military veterans.

That legacy has continued through the push for FDA approval of the psychedelic drug MDMA.

National Health Reporter Erin Billups takes a look at the call for greater access in this second installment of our Exploring Your Health series on PTSD.

What You Need To Know

- Psychedelic drugs show promise in treatment for PTSD

- Some veterans are pushing for expanded access to psychedelic drug treatments

- Mental health advocates fight to decriminalize, or even legalize, psychedelics

After serving for four years, with three combat deployments in Afghanistan, Army Ranger Jesse Gould said re-entering the workforce was harder than he imagined.

“I was excited for the next chapter, that I was going to hit the ground running,” said Gould. “I had this finance degree and everything that Ranger Regiment had taught me and the confidence involved with it.”

He thought he’d hit the ground running because he hadn’t thought his service was traumatic.

“There was never this case where somebody died in my arms, or everything just just went to hell,” said Gould.

But he said he wasn’t ok. Shortly after returning stateside, Gould started noticing symptoms he couldn’t shake.

“I was fortunate enough to see the red flags,” said Gould “Just being so depressed, having to miss work because of anxiety, panic attacks, medicating with alcohol because I didn't know any other way to just move on to the next day without just struggling and suffering.”

Gould believes his body was in shock. “Your brain is at this heightened cortisol, heightened stress because you're always on alert, you're always hyper vigilant,” said Gould. “You're always ready to react at a moment's notice.”

Gould was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He believes his symptoms are also evidence of traumatic brain injury from operating mortar systems and the effects of no longer being surrounded by the brotherhood of the military.

“Just constantly having these explosions near my head caused inflammation, caused damage and I had to figure this out myself,” said Gould.

He sought help at the Department of Veterans Affairs. They offered therapy if he took selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), medication typically used to treat the symptoms of depression and anxiety. But Gould wanted something that could get at the root of his trauma. He saw an opportunity with psychedelic drugs.

“At first I was looking into it casually, then it just became okay, let me try this, I need something,” said Gould.

Gould quit his finance job and bought a one-way ticket to Peru. He says he found healing through shamanic sessions with the hallucinogenic drug ayahuasca.

“It did feel like my brain was reset. It felt like before - a misfiring engine and it actually felt like it was working as it should for the first time in quite a while,” said Gould.

Now he is on a mission to help other veterans find relief. In April 2017, he started the Heroic Hearts project, which connects veterans with PTSD to psychedelic programs in other parts of the world.

“It was just this question in my mind of, ‘hey, did you stumble onto something that could potentially help a lot of people?’ And that was a yes,” said Gould.

Meanwhile, The Department of Veterans Affairs has finally turned its attention to the potential of psychedelic medicine.

“I think that we have a moral obligation to do what we can to advance any treatment that will help this group,” said Dr. Rachel Yehuda. A professor of psychiatry and neuroscience of trauma at the Mount Sinai Icahn School of Medicine.

Yehuda has been treating patients with PTSD for approximately 35 years. She is currently leading a study at the VA, exploring whether MDMA-assisted therapy offers healing to veterans with the disorder. Her team uses imaging to look for signs or biomarkers in the brain.

“It would be wonderful, and I think possible, if we could develop a profile at baseline,” said Yehuda, “that would help us understand who is likely to be a responder or a non-responder.”

Yehuda said the push to find healing for mental conditions has often been fueled by veterans.

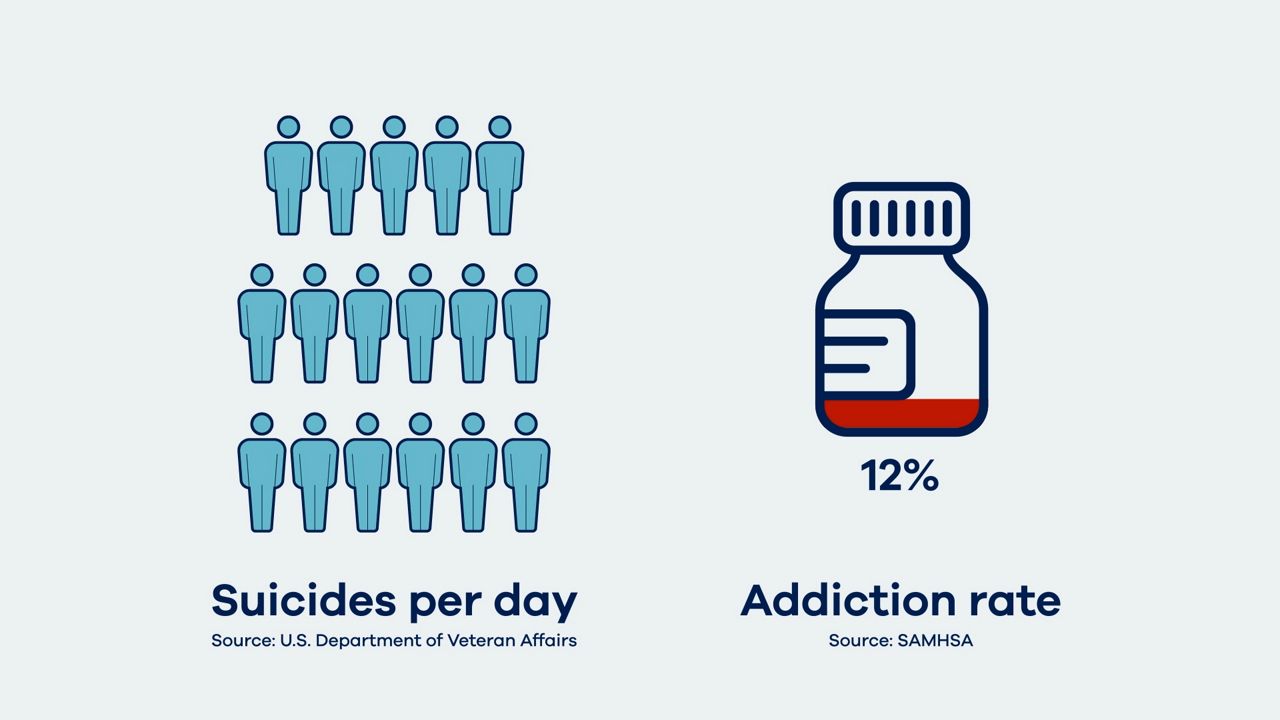

“It's been very difficult to offer combat veterans treatments that really stick. Veterans also have a very high rate of suicide,” said Yehuda. “They often have a lot of other problems and complications as well.”

Some doctors were treating patients with MDMA in the 1970s, recognized then for its ability to reduce anxiety, lower defensiveness and feel closer to others. By then it was already a popular party drug and the war on drugs had begun which led to heavy restrictions on the use of psychedelics.

“Once you designate a compound as schedule one, which means that there's risk of harm and no potential therapeutic benefit,” said Yehuda, “It becomes difficult to make the argument that no, no, no, we still think that there could be therapeutic benefit.”

Yehuda’s research at the VA is funded in part by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies known as MAPS. The nonprofit has crowdsourced funding for over 20 years of psychedelic research.

“There was stigma, and the research did slow down and it's taken a long time to undo and educate and produce the data that was necessary to help start to change people's minds and have them see these as potential helpful tools,” said Yehuda.

Amy Emerson is CEO of MAPS, Public Benefit Corporation, a spinoff from the main organization.

Her team is focusing solely on ushering MDMA-assisted therapy through the clinical trials and regulatory process. She says so far the findings are consistent, durable and promising.

“Three treatments with MDMA-assisted therapy, about one month apart. Measuring that two months later,” said Emerson. “On their social, family, work life, all three of those functional areas, they were better able to engage, and it was measurable.”

With clinical trial publishing complete, MAPS PBC is applying for FDA approval.

If it is approved, that decision would come in 2024. The team has successfully worked with the American Medical Association to create a coding system which builds a framework for billing through insurance.

“More people are likely to seek treatment. If there's a treatment that is working and available and paid for,” said Emerson.

So far Gould’s Heroic Hearts Project has helped shuttle more than 500 veterans and over 100 military spouses overseas for psychedelic experiences, which he says has led to real healing in the community.

But Gould says much more needs to be done, with nearly 17 suicides a day and more than 12% of veterans entangled in addiction.

“It's ridiculous for veterans to have to go to other countries to get lifesaving mental health care,” said Gould.

Heroic Hearts is advocating for wider access to psychedelic substances in the U.S. both within the medical system and through decriminalization, particularly for vets.

Gould said as things stand now, only those with the right doctors or connections have access to psychedelics.

“This sort of, I think, monopolization of how you can heal,” said Gould. “It's not about actually thriving and doing well in life.”

Still, scientists like Yehuda and Emerson find comfort in the clinical approach, citing its safety.

They all agree on one point, that once access to psychedelic drugs is granted, there is a potential for greater societal healing.

“Trauma doesn't in fact affect just an individual person. It's like it goes up from there, it affects them and then it affects their family and then it affects their community and then it affects the way they engage in the workforce,” said Emerson. “So starting to heal an individual's trauma is also going to have that ripple effect.”

If FDA approval is granted, MDMA must be rescheduled to be legally accessible for patients. There's also simultaneous work underway seeking compassionate use access to psychedelics. The world, though, is not waiting for governments to grant access. As use of the drugs grows, public education and harm reduction support is desperately needed.