This story is part of Spectrum News NY1's special reporting on the coronavirus pandemic in New York City. Join us at 8 p.m. on Saturday, March 13 to watch "Coronavirus Remembrance: Stories from the Epicenter" on Spectrum News NY1 or the Spectrum News app.

It seemed that everyone in East New York knew Winchester Key.

After nearly two decades as a top legislative assistant in the New York State Assembly, he served as board chairman of the community development group the East New York Urban Youth Corps, and led the local police precinct council, school board and Lions Club.

Even after losing his eyesight to diabetes, he continued to organize marches and lead church groups, said Nikki Lucas, an East New York activist and candidate for City Council.

But he died alone in an East New York hospital in April, four days before his 73rd birthday, according to his son.

“We didn’t get to give him a proper sendoff,” Lucas said. “Not being able to celebrate the impact he had on this community, it affects you deeply.”

“There’s no closure,” she said.

Key is one of the 112 people who died from coronavirus in a pocket of high-rise towers and senior living centers at the far edge of Brooklyn, the 11239 ZIP code. It’s a peninsula built on a former landfill in Jamaica Bay, sandwiched between the wide thoroughfare of Flatlands Avenue and the Belt Parkway that runs along the bottom half of the borough.

The area includes the Spring Creek Towers, referred to most commonly by its original name, Starrett City, the country’s largest federally subsidized housing complex, as well as a New York City Housing Authority development and an assisted living facility.

Other neighborhoods saw a higher total number of deaths, but 11239 holds a tragic mark of distinction: Its 112 deaths represent the city’s highest rate of COVID-19 mortalities per capita, according to city estimates.

A city Health Department spokesperson said they could not specify in which housing complex the area’s residents who died from COVID-19 lived, citing privacy rules. A spokesperson for Twin Pines Management, the company that runs the Starrett City towers, says they are aware of 28 known or presumed COVID-19 deaths among their tenants. Families of deceased residents are not required to disclose a cause of death.

Twin Pines also disputes the city’s population estimate for 11239, noting that its count of its own tenants -- 18,000 people -- lowers the per capita rate of COVID-19 deaths. Yet even accounting for a larger population, the ZIP code’s death rate remains among the city’s highest.

The 11239 ZIP code shares many characteristics with other epicenters of the virus in New York City: It is home to a majority nonwhite population, with high rates of poverty and diminished access to health care resources.

What makes this area different is its elderly community, with twice the proportion of people over 65 years old than the city as a whole. That’s due in part to the senior homes, but also to the number of decades-long residents of Starrett City, built in the 1970s to be an isolated town unto itself.

Now, residents say the isolation of their peninsula played a significant role in their fate during the pandemic.

For much of last year, the community had little access to coronavirus testing. And despite the governor and the mayor’s stated focus on getting vaccines to the communities hardest hit by the virus, it was not until this past weekend that the area got a vaccine site with slots reserved exclusively for residents of 11239.

Interviews with more than 20 residents, community figures and elected officials revealed a portrait of a diverse community still making sense of their losses and working to make their voices heard.

“Not only in the pandemic, but in general, we’ve been left alone, and we’ve been left behind,” said Ana Santiago, a resident of 30 years and the president of a new tenant group in Starrett City focused on advocacy and education. “It’s almost like the world is moving on, and we’re still stuck in this bubble, in this community, and we’re not moving along with the world.”

"A Neighborhood Unto Itself"

The goal of Starrett City was to create a self contained “nucleus,” said Robert Rosenberg, Starrett’s manager for its first two decades and the former housing commissioner of New York City.

The hope was that suburban amenities -- playgrounds, a fitness center with an Olympic-size pool, two public schools and the development’s own energy generation plant -- could attract families that might have taken the path of “white flight” out of the city during a period of economic downturn.

“It was a neighborhood unto itself,” said Carol Lamberg, the former executive director of the Settlement Housing Fund. “It was naturally contained and also big enough to be its own little town.”

In the 1980s, a lawsuit brought by the NAACP and challenges from federal prosecutors ended the development’s initial quota of 70% white families, leading to an influx of Black and Latino families. A few years later, the fall of the Soviet Union brought hundreds of Russian and Bukharian families.

Prizing their diverse community, generous apartment layouts and ample green space, many residents have stayed for decades. Today, about a third of the ZIP code is at least 65 years old, according to census estimates.

State Sen. Roxanne Persaud, who represents the area, says tenants appreciate the isolation.

“When you go to Starrett City, people still want to be left alone,” Persaud said in a phone interview. “They want that isolation, they want to be away from everything, they want to be a self-contained community.”

But many residents we spoke with disagree.

“We’re a forgotten community,” said Maria Morello, who was raised in Starrett City and returned 12 years ago.

In the decades since the development opened, Brooklyn’s East New York area has seen broad disinvestment, stagnating incomes and declining access to health care. A study published in April 2020 led by the top city Health Department researcher found that East New York and Starrett City had the second-highest number of health disparities of any community district, and was at high risk of being overlooked for public health interventions.

The medical offices in Starrett City closed, leaving only a dentist in its shopping center. The closest hospital, Brookdale University Medical Center, two miles away, is consistently rated among the worst hospitals in the nation, while a nearby Brookdale clinic is many residents’ last choice for care.

“This is a disenfranchised population,” said Jerry Ramos, a senior vice president at the Institute for Community Living, a nonprofit health services provider. “It’s not because of people not wanting to get better, it’s because they don't put the resources here.”

"You Lost A Friend"

During the early days of the shutdown, an eerie silence overtook Starrett City, punctuated only by the sound of sirens.

Residents say the only vehicles they saw drive through Pennsylvania Avenue, the busy street that runs through the center of Starrett City, were ambulances. By mid-April, one resident notes, the ambulances began simply parking in rows in the shopping center’s lot, waiting for emergency calls that were sure to come.

The initial days of quarantine were chaotic. Multiple residents reported being price gouged for eggs, water, milk and other basic food items at the shopping center’s City Fresh Market grocery store. (The store did not respond to an emailed request for comment.) After a citywide drought of cleaning supplies, a crowd of people gathered at the nearby CVS in response to rumors of a new shipment of Lysol wipes -- which turned out to be false.

As the Twin Pines management went remote, building janitors worked longer hours, increasing their overtime costs 200% compared to April 2019, according to a spokesperson for the company. The staff of the development’s power plant prepared to quarantine within the plant to keep the power on, the spokesperson said.

Inside the buildings, most residents isolated, while some didn’t. When she didn’t see signs from management about social distancing and mask-wearing, Theresa Davila, a retired nurse, put up her own: “Choose your mask,” it read, over pictures of people in face masks and a man intubated in a hospital bed. (A spokesperson for Twin Pines said they sent 10 notices about COVID-19 to residents in the first month-and-a-half of the pandemic.)

The centers of elderly living around Starrett City saw early and dramatic numbers of deaths from COVID-19. Boulevard, a 184-bed assisted living facility across from the towers, had 19 deaths, according to a revised tally of nursing home deaths released by the state Health Department in February. (A representative for Boulevard did not respond to emailed requests for comment.)

Simone Dundas, the director of the Vandalia Senior Center in the peninsula’s NYCHA development, said that 11 of about 290 senior residents died from the virus, adding grief to their isolation in the days before they were able to set up classes by Zoom, when her staff had time to call each household once per day.

“It’s hard for them hearing, you lost a friend, a person you may have been sitting next to for the past 20-plus years, or a neighbor on the same floor as you,” she said.

In late April, Raymond Daniels, a 30-year resident, learned that a longtime neighbor had died, the mother of four adult sons. She had lived next to Daniels on the first floor of their building, sharing food from local food pantries with him. She was known for passing her sons’ old clothes onto other neighbors.

One day, he saw the sons in the lobby, dressed in black. When he sees them now, he says he doesn’t ask too many questions, to not invade their privacy.

“No one wants to get into anyone else’s business,” he said. “We always say, God bless, and stay safe.”

"The Epicenter of the Epicenter"

In late May, the city released data for cases and deaths by ZIP code. For many 11239 residents, it was the first they knew of just how badly the area had been hit.

Keturah Smith, a Starrett resident of five years, checked city data sources multiple times a day through the first two months of the pandemic, noting that the available metrics had shown Starrett City in a safe pale color.

“It went from that, to literally purple, and the highest deaths per capita in the city,” she said.

“From the outset, we knew that based on circumstances and history and data and the conditions, the health conditions that have very alarming touch points in terms of our district, that we would be hard hit,” said City Council member Inez Barron, who represents the area. “Until we forced the issue and made sure that that data was forthcoming, we could only speculate.”

Politicians descended on the community, speaking to residents and reporters and distributing masks, but, residents said, they haven’t been seen much since.

In a May 29 issue of the Spring Creek Sun, the development’s community newsletter, Twin Pines included a letter to residents addressing the newly released data, saying that the COVID-19 deaths known to the management represented only 30% of the city’s total for the ZIP code. The issue featured a traditionally lighthearted, seasonal cover, with a picture of a butterfly landing on a blooming red aster and the words, “First Sign of Summer.”

“Based on self-reported information from members of our community, we do not believe that the majority of the reported COVID-related fatalities within the entire 11239 ZIP code stem from Spring Creek Towers,” the letter read. “We will continue to monitor the situation carefully.”

For some residents, learning of the extent of the area’s deaths, combined with a sudden and brief influx of media and political attention, only deepened their sense of isolation.

“We were the epicenter of the epicenter, and people did a few campaigns where they handed out two or three masks, and maybe some hand sanitizer, and that was it,” Theresa Davila said. “We were a big story at first, and now nothing.”

So in August, when management decided to phase out assigned parking in the development’s garages in favor of first come, first serve, it gave residents something to fight for.

“That upset the residents here very much,” Santiago said, adding that tenants with disabilities like herself were concerned they would lose cherished spots with easy access to elevators.

A petition against the measure gained 1,200 signatures on the app Nextdoor, Smith said. Management later dropped the plan.

Santiago, Smith and several others decided to form a new resident group, the Spring Creek Towers Resident Alliance.

Santiago said she wanted to address what she sees as a long-term breakdown in communication between management and residents that worsened during the pandemic, and to fill the hole of tenant connection that had been left when Starrett City’s longstanding Tenant Association stopped holding meetings last March. (The Association recently resumed meetings remotely.)

“We had a failure here,” Santiago said. “This landlord here provided no information to the residents. It was almost like the pandemic wasn't existing.”

A spokesperson for Twin Pines said each time they learned about a resident receiving a positive COVID-19 diagnosis, they put a letter in the lobby of the resident’s building to notify the other tenants. The spokesperson said that residents are not obligated to inform them of COVID-19 diagnoses or of causes of death, though they encourage them to do so.

The Alliance now holds meetings once a month. Their email list has grown to include 180 residents, Smith said.

“It turned from, ‘Hey, are you okay, let us know what’s going on,’” she said, “to, here’s a workshop on know-your-rights, tenant organizing, recertification workshops, eviction moratorium and COVID hardship relief.”

"We Need to Do Better"

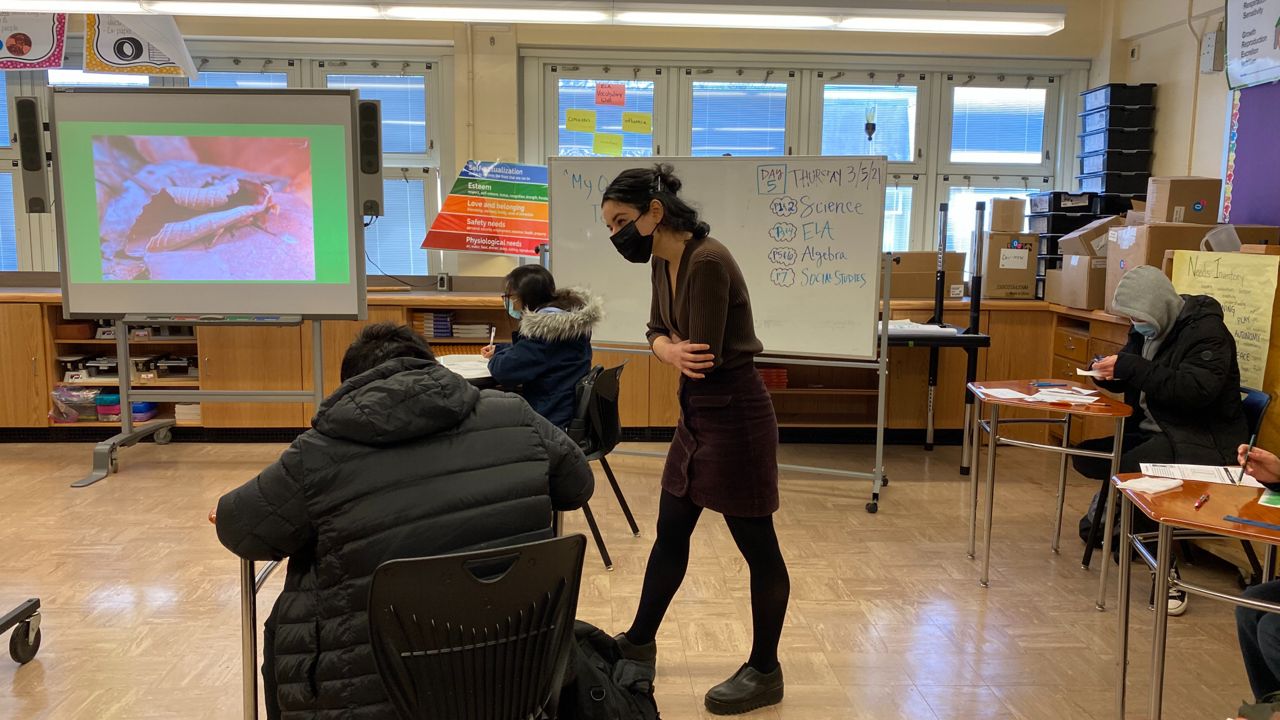

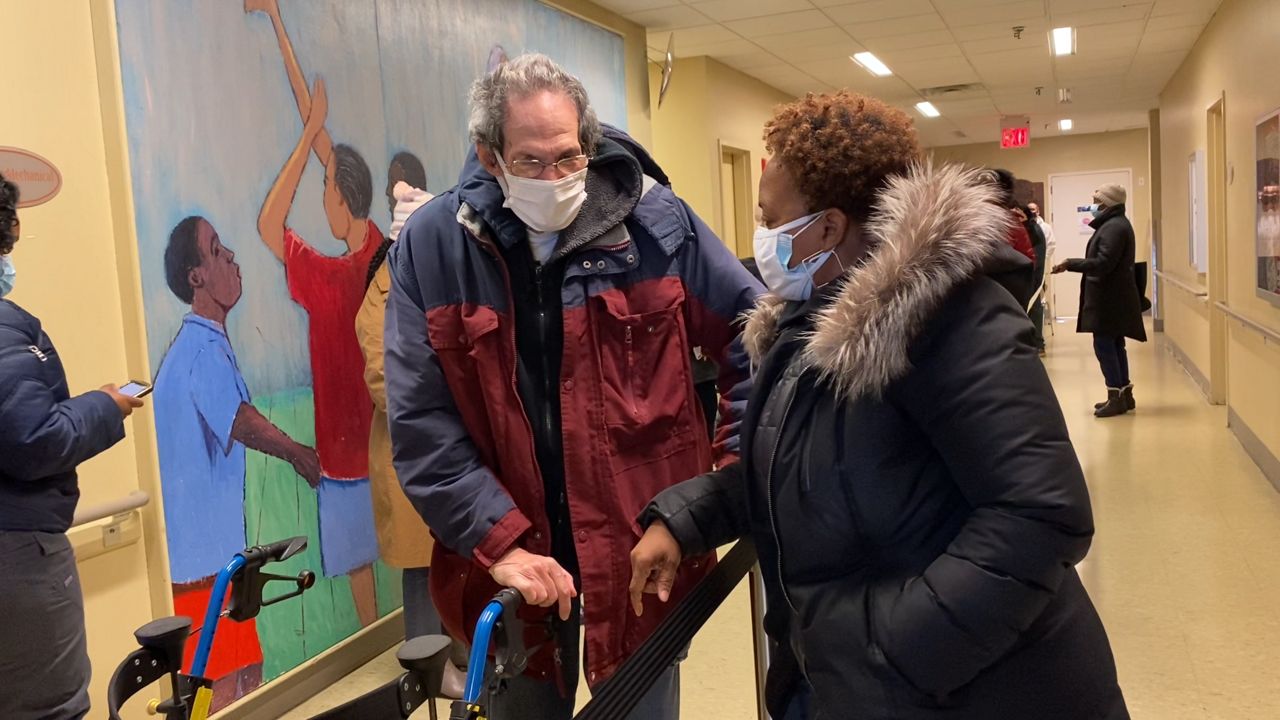

This past Saturday, residents of 11239 shuffled into the senior and teen programming area under Starrett City’s athletics complex, lining up alongside painted murals of children playing in the fields between the towers to finally receive vaccines meant just for their community.

Many felt it was a long time coming. Starrett City had only received a permanent testing site in October; a spokesperson for Twin Pines said they first offered space to the city for a testing site last March. Nearby vaccine pop-ups, like at the Christian Cultural Center within the ZIP code, had drawn some residents, while others arranged for vaccines elsewhere in the borough.

Over the winter, virus fears had returned full tilt to the area. The case rate for 11239 through the city’s second wave frequently peaked at much higher than the rest of the borough. Vandalia Senior Center lost another member in January, Dundas said, a man known for handing out sweets on every holiday.

When Valentine’s Day came, Dundas said, there were two candy hearts missing from her office desk.

“We all said it – if he was here, he would be giving out chocolate,” she said. “Simple things, simple things.”

As the state’s vaccine rollout began in December, the management had asked local politicians to help them lobby Cuomo to place a permanent vaccine site in the gymnasium of Starrett City’s athletic center. Barron, the City Council member, sent a letter of support for the site to Cuomo; Persaud said she spoke personally to Cuomo about it, who she said told her he would “work on that.”

Yet no permanent site materialized. When the state opened a mass vaccination site at Medgar Evers College in February, for its first week, it did not include the 11239 ZIP code in its area of eligibility.

Barron called Cuomo’s response to the pandemic “seemingly racist.”

“I would have thought that Starrett City would be the number one location” for a permanent vaccine site, Barron said. “They should’ve been called to the table right away.”

“Governor Cuomo has made equitable distribution the centerpiece of the state’s COVID-19 vaccination program,” said Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the state Department of Health. “While the limited supply of doses remains a factor, we continue to expand our efforts and are doing all we can to make vaccines available in every hard-hit community in the state.”

Plans for the vaccine site were first shared with elected officials and Starrett City management on the Tuesday ahead of its opening; management sent emails and text messages with a sign-up link to Starrett City residents the next morning. On Friday, Persaud said that its slots would be reserved exclusively for 11239 residents, and that her goal was to get 30% of the area vaccinated by the end of the weekend.

By Saturday morning, some of the protocol had changed. Due to low sign-up numbers from 11239, residents from three other East New York ZIP codes were now eligible to get vaccinated, and the site would take walk-ins. Health workers administered more than 900 doses through Sunday evening, Bruno said.

By Wednesday of this week, city data showed that percentage of adults partially vaccinated in 11239 had more than doubled, to 18.6%, with 9% fully vaccinated. Citywide, 19% of adults have received at least one dose of vaccine.

“We are scaling up sites every day and the single greatest barrier to vaccinating more New Yorkers is the supply,” a spokesperson for the city’s Health Department said in an emailed response to questions about the vaccination effort in 11239.

Persaud got her vaccine in the morning, posting pictures of the shot to her Facebook page, to combat ongoing hesitancy to take the vaccine in the area. After waiting two months for a vaccine site here, she said, she wasn’t focused on the past.

“We’ve passed the stage of whether they should have had it there earlier,” she said. “It’s, now that we have a site, we have to ensure that the people are getting the vaccine.”

Lucas, the City Council candidate and a 30-year resident of Starrett City, got on Facebook Live shortly after arriving to tell her supporters and neighbors they were eligible to get their vaccine there. But she said the state should have put the information about the site much sooner, so elderly residents could arrange transportation.

“We need to do better,” she said.

While some residents came for shots, others came just to see friends and check out the operation. Rebecca Caraballo, president of the Tenant Association, kibitzed with one of the security guards, greeting people on their way down the handicap-accessible ramp.

Fran, a 21-year resident who asked to be referred to by her first name to protect her privacy, stopped by ahead of a doctor’s appointment, but said she wouldn’t get the vaccine -- she feared it hadn’t been properly researched and tested, and that it may worsen her chronic inflammation.

But a few hours later, she was back. Seeing her neighbors and friends line up was a “reality check,” she said.

“I’m looking at people fighting for their lives to get the vaccine, so they won't pass, or they won't get sick,” she said. “It actually shows me that this is something we all have to do.”

Finally accepting the vaccine, she said, made her miss the people the community had lost even more. She thought of her neighbor Elmer, a resident since before she got to Starrett, who cared for stray animals and would call her at night to have long talks and tell her Bible stories from Genesis and Revelations.

He died in October after contracting COVID-19 while in the hospital for other health issues.

“He came with the pavement,” Fran said. “Not a lot of people knew him. They looked at him and judged him by the way he looked, but let me tell you, he had a heart.”

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story said that Inez Barron is a resident of Starrett City. She is not. She represents the area in the City Council.