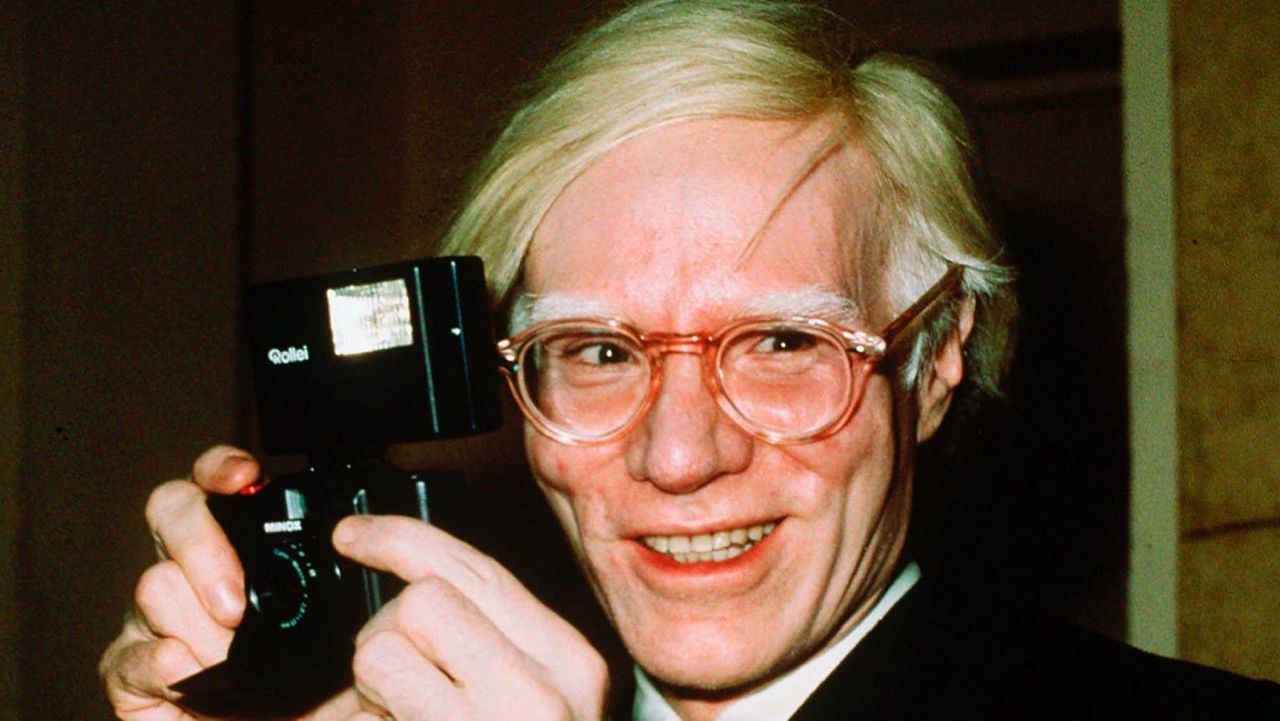

The Supreme Court will hear a petition between the foundation of late artist Andy Warhol and photographer Lynn Goldsmith, seeking to determine the nature of transformative works and copyright.

The lawsuit concerns art from 1984, when Warhol was commissioned by Vanity Fair magazine to create an image based on Prince, the iconic musician whose profile had exploded by the mid ’80s. But Warhol’s Prince artwork was based on a cropped photo by Goldsmith, which was taken three years earlier and to which she held the copyright.

According to the Warhol Foundation, Warhol — who died in 1987 — was seeking to “comment on the manner in which society encounters and consumes celebrity.” But, according to Goldstein, the photo was only to be used as a reference one time, and could not be used for anything other than that 1984 issue.

After Prince’s 2016 death, Vanity Fair published Warhol’s work — which had expanded from the one image to a series of Prince prints — in a tribute issue. Goldstein was surprised to see the Warhol image, finding it identical to her own work.

“I went and looked at my digital archive and went, those are the eyes,” Goldstein said in a brief her counsel submitted to the high court. “Not just the outline of his face, his face, his hair, his features, where the neck is. It’s the photograph.”

Goldstein's discovery soon led to a run of lawsuit threats, actual lawsuits, and counter-suits. At the heart of those lawsuits stood the nature of copyright infringement, transformation of artwork, and fair use. Goldstein, in her counsel's brief to the Supreme Court, said a district court decision ruled in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation, based on a “fair use” defense, finding Warhol’s work to have changed the mood and meaning of the original photo.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision, holding that a court is “forbidden from trying to ‘ascertain the intent behind or meaning of works at issue.’” Instead, the court wrote, a judge must determine if a secondary work uses its source material in a “fundamentally different and new” way — that it must “at bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work.”

So the question before the Supreme Court is to determine whether a work of art is considered transformative when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material, or if a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of an accused work.

The Warhol Foundation’s attorneys argue that the Second District’s decision “hollowed out” fair use defenses, and argues that the opinion will have a chilling effect on artistic transformation of existing works. “Even if the Second Circuit’s decision is narrowly cabined to commercial reproductions—and there’s no reason to think it will be—the ability to reproduce works is of central importance to artists, galleries, and museums,” wrote the foundation’s attorneys.

Goldsmith’s attorneys argue that the Warhol Foundation’s attorneys are taking a “Chicken-Little” approach, noting that the Second District opinion “repeatedly endorsed other examples of artworks that directly copied from an original yet were nonetheless transformative.”