It has become a familiar sight on Staten Island: police barricades lining the streets, marking sites of protests. Protests against the city’s plan on how to handle the influx of migrants arriving in New York from the southern border.

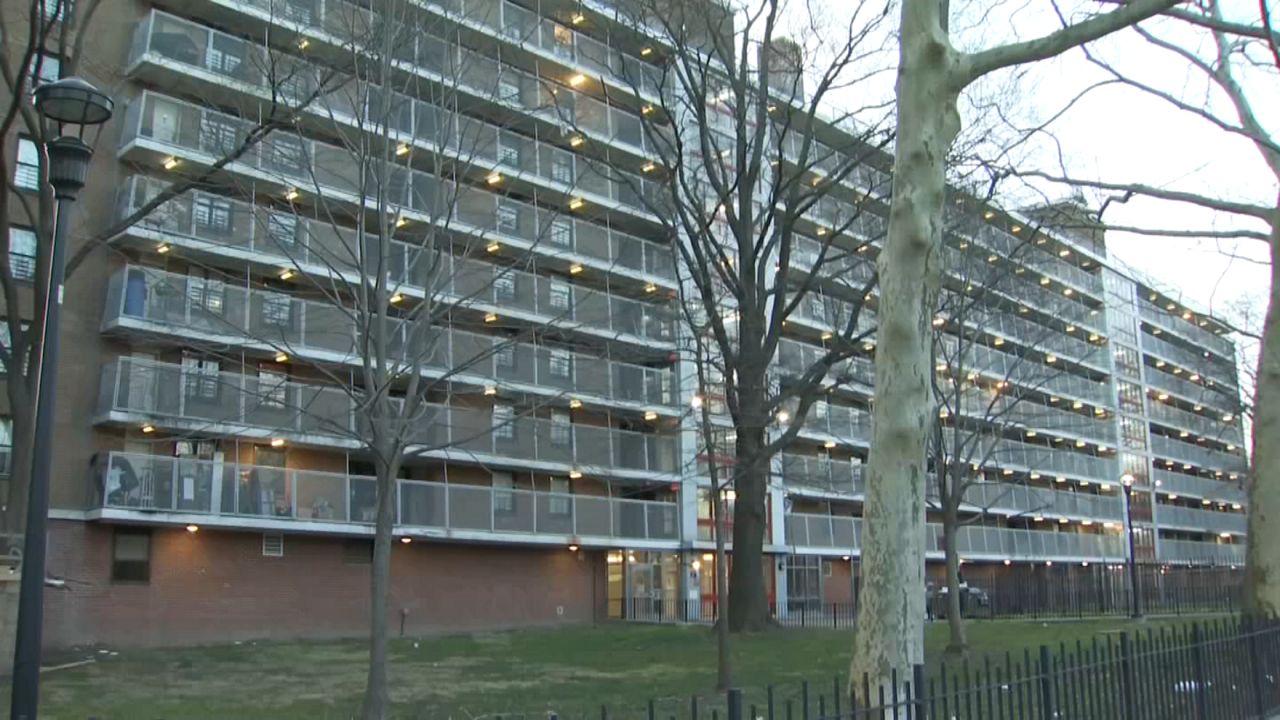

Island Shores in Midland Beach is a former senior living facility. The latest numbers from the city show it's now home to 185 migrants.

That includes Rosa Velasco and her family.

What You Need To Know

- Protests against the city’s handling of the migrant influx have become a familiar sight on Staten Island

- According to City Hall, less than 2% of the newly arrived migrants are housed on Staten Island

- Island Shores in Midland Beach is a former senior living facility. The latest numbers from the city show it's now home to 185 migrants

- A former hotel-turned-shelter on Wild Avenue in Travis has been open since October of last year

“Americans yell at us, they insult us, they say bad things to us. They speak poorly about all of us, that we are all killers, murderers. That they don't want us here because we are killers, murderers, and all that stuff” Velasco said through a translator.

Velasco, her husband and their two children are from Ecuador.

"The journey was very dangerous. Very hard for me and my kids, because we also crossed forests, we made many stops along the way, and we came in a train called the 'Beast,' through rivers,” she said.

Just a block away from Island Shores is Lada Doggy’s Day Spa. Inna Elin is the owner.

“It’s not comfortable to me or my customers. I’d love the shelter to be somewhere else,” Elin said. "This is a woman-run business. I am mostly here by myself, and I don’t know who is in the shelter and how they are going to act."

Elin emigrated from Moldova 33 years ago.

“Moldova was in a war, so we were running. It was Russia against Moldova. It wasn't easy there. I was 19, my parents decided to keep me away from that war, and they sent me here” Elin said.

She says she relates to the struggles many migrants face, but doesn’t think a residential neighborhood with small businesses is the right place for a shelter.

“I feel for them. They need help. You can't take from one people and give it to another people. I didn't get no help. I didn’t get no shelter. I didn’t get nothing. I did everything by myself," Elin said.

Elin says she’s lost business because of protests, that barricades make it difficult for some dog owners to park close to her shop. Still, she believes residents should continue to demonstrate.

“It worked for Villa, protests” she said.

She’s referring to the former St. John Villa Academy in Arrochar: an empty school which the city turned into a migrant shelter. For months, thousands from the community showed up night after night calling on the city to shut it down.

In October, the fire department issued a full vacate order, saying the building had no sprinkler system or working fire alarms. Staten Island Borough President Vito Fossella said 170 migrants occupied the site.

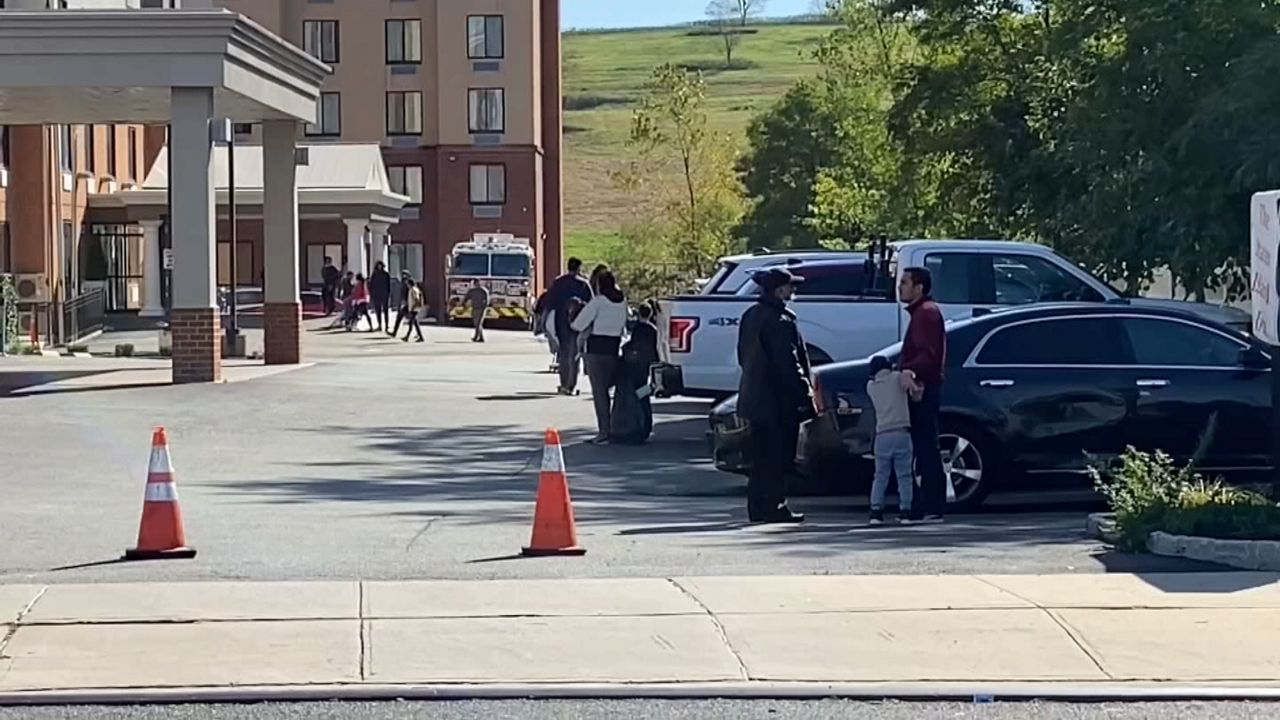

According to City Hall, less than 2% of the newly arrived migrants are housed on Staten Island. A former hotel-turned-shelter on Wild Avenue in Travis has been open since October of last year.

Gabriel Castelo and his family have been staying at the site for more than a month. "I don’t know if I could stay a year, six months, or two or three months," Castelo said.

Castelo, his wife and their 3-year-old son made a 15-day journey from Ecuador to Arizona before getting on a bus to New York.

“The entire journey, since I left Ecuador, the entire journey was hard. And it’s also very hard to be here, it’s not easy, it’s really hard. Because of the lack of a job, the fact that I can’t speak to someone in English, it’s a lot of things. When I left my country, I thought, 'When I get to the U.S., I’ll look for a job, without a problem.' But in reality, that’s not how it is here," Castelo said through a translator.

Castelo, too, says migrants staying at the Wild Avenue site are welcomed by protests.

“I don’t remember the exact day or the date, but yes, right out here they had a protest with a lot of people chanting that we should leave,” he said.

John Aspinall, who lives in Travis, says protestors there are shedding light on quality-of-life issues they say have been caused by shelter residents.

“By no means is it anti-migrant or pro-migrant or whatever it may be. It's all about accountability” Aspinall said.

“The issues at hand are going to be driving with no license plates, driving with no licenses, driving, and now crashing into vehicles in our community” Aspinall added.

Aspinall says residents have noticed unlicensed vehicles or vehicles with fake plates parked in the shelter’s lot.

NY1 was not allowed to walk onto the property, but while there, saw a number of cars in the lot with no license plates, only one plate or with paper plates.

"Literally, as I was dropping my kids off at school, I circled back around. Someone came out of the shelter with no plates on their car. I followed them all the way to Forest Avenue, me taking a video all the way back, no registration, no plates, no nothing," Aspinall said.

He says that’s just part of the problem.

“What happens is the migrants come outside and they want to go into the parking lot and barbecue with propane tanks on the street,” he said. “If you're going to be here, you have to follow the rules and protocol that every New York City citizen has to follow."

Asked if he sees anyone breaking the rules at the shelter, Castelo, through a translator, said: "No, honestly, no."

"I haven’t seen or had a problem with anyone, because we just spend time in our rooms and don’t really go out," he said. "We haven’t seen any of that, really."

In a statement, a spokesperson for the city's Department of Social Services said in part, “In order to maintain a safe and secure environment, on-site security is present at all [Department of Homeless Services] shelter facilities and provider-partner staff will meet with clients, as necessary, to discuss the importance of aligning with relevant laws, shelter rules, and good neighbor policies both in and around the facility.”

Despite all of the backlash, both Velasco and Castelo still have dreams of making a life here in America with their families.

“Now I'm getting help with my son’s studies, but the work, I don’t see that. No, no, I mean I don't know if they're waiting for help, but we do have to wait with patience and ease to get a little more help," Velasco said.

“We came for a better future. A future for my son," Castelo said.