We get it.

With a record-shattering, nonstop onslaught of an Atlantic hurricane season in 2020, the last thing you probably want to think about is more hurricanes.

So with that in mind, there's some good news and some not-so-good news about what 2020 could tell us about 2021.

First and foremost: It’s too far from the start of the 2021 season to really get a great sense for what might come.

“You really have to get a look at the patterns around May 1 to know what June through November might hold,” said Spectrum News Chief Meteorologist Mike Clay, based in Tampa. “There is no telling.”

Long-range tropical and seasonal forecasting is still very much in its infancy, and more than six months from the start of the next hurricane season, a lot can and will change. We’re still months away from accurately assessing or even dipping our toes into most key long-range meteorological metrics.

But even with that in mind, there's perhaps at least a little that we can look at with more than six months to go until June 2021, including the history of previous big hurricane seasons and what followed immediately afterward.

The main meteorological indicators about what the 2021 season could hold are too far into the future to accurately assess now. More on that in a minute.

The one definitive metric that we do have, though, is history. This is where, at least on the surface, there's at least a smidge of good news.

The 2020 season recently topped the 2005 season in terms of total named storms, so perhaps the 2006 season might be the first place to look for clues about what 2021 may hold.

The good news is that the 2006 hurricane season fell below average, producing only 10 named storms and five hurricanes, both below the long-term full-year averages of 12 named storms and six hurricanes in the Atlantic.

The relative bad news, though, is that the primary culprits for those low-end totals in 2006 were a developing El Niño event and a persistent layer of Saharan dust in the Atlantic Ocean. Again, it’s just way too far out to say if those things will be in play for next summer and fall.

And with a sample size of one, there’s simply no way we can attribute the low-end 2006 season to what might happen in 2021 with any kind of accuracy.

So with that 2006 micro-sample size in mind, let’s expand our view a bit to include some of the biggest hurricane seasons over the last 100-plus years.

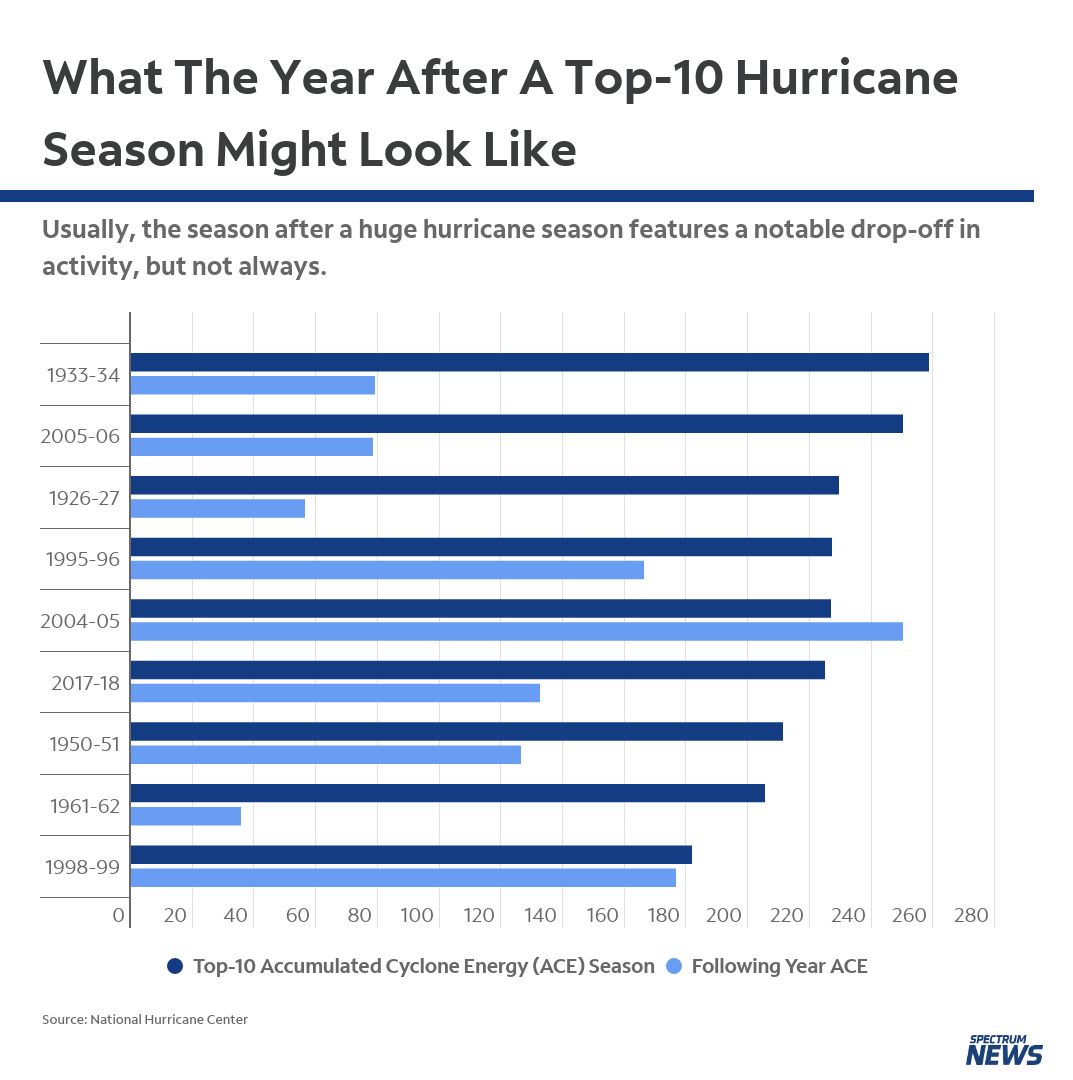

If you average the top-10 seasons since 1900 in terms of Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), the most widely used metric for assessing a hurricane season’s overall intensity, you’d get an average ACE of 219.5. An exactly average Atlantic season features an ACE of 100, so 219.5 signals a hurricane season with more than double the average of tropical systems.

If you average the nine years that followed a top-nine season in terms of ACE since 1900 (2020 is number 10), you’d get an average ACE of 122.38, a notable drop-off but an indicator that, on average, an above-average-but-not-off-the-charts hurricane season could be in the cards.

Then again, the record-smashing 2005 season followed an almost-as-big season in 2004. Simply put, history offers a scattered, at best, view of what the year after a huge hurricane season might look like.

But, at the very least, there is some historical precedent for at least a slight reprieve after a big season like 2020.

It's arguably the single-most-important determining factor in a long-range forecast, or for at least a top-level view about how a tropical season could play out.

The ENSO cycle is the measure of sea-surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean. THe cycle states that warmer-than-average temperatures in the central Pacific is an El Niño, while cooler-than-average readings are a La Niña.

Generally speaking (though with notable exceptions), El Niño events can lead to below-average seasons, and La Niñas produce above-average seasons.

In short, an El Niño creates a meteorological domino effect of global weather that often ends up boosting wind shear across the Caribbean and the Atlantic, tearing apart storms before they fully develop.

A La Niña, meanwhile, reduces wind shear and can create a more favorable environment for the formation of tropical systems in the Atlantic.

A moderate-to-strong La Niña is in place, and it’s widely cited as one of the key puzzle pieces for the record-breaking 2020 season.

Currently, the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) confidently predicts the current La Niña to persist into the spring of 2021. Beyond that, though, uncertainty grows about what the ENSO cycle could look like in the summer and fall of 2021.

“La Niña is likely to continue through the northern hemisphere winter 2020-21 (~95% chance during January-March) and into spring 2021 (~65% chance during March-May),” the CPC wrote in its late November memo.

Watch this closely, though: Some computer models are hinting at moderating sea-surface temperatures in the central Pacific, perhaps an indicator that the current La Niña may start to relax next year.

If you’re a weather buff, you probably know that sea-surface temperatures are also one of the main indicators of what the upcoming tropical season could look like.

Warmer sea-surface temperatures act as fuel for tropical cyclones. The warmer it is in the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic Ocean, typically, the more favorable the environment there is for tropical cyclone formation.

Dust from the Saharan Desert can also limit tropical development in the Atlantic, especially earlier on in the season.

These two metrics are where it’s basically impossible to get any sort of pulse. At this point, we simply don’t know what sea-surface temperatures, the Saharan dust layer (SAL), and other critical and shorter-range factors like the Madden-Julian Oscillation, Atlantic high pressure and Rossby waves will look like across the Atlantic in six months.

We certainly don’t want to leave you with a cliffhanger, but we also don’t want to mislead you.

While there are a few hints about 2021, the reality is there’s just not much we can gather from the current data about what the 2021 hurricane season might look like. Hopefully, though, we won’t have to deal with 30 named storms in a single season again anytime soon.