While we all know about the devastation a hurricane can unleash, there are several things about them that you might not know.

And in some cases, these key bits of information could help you better anticipate and prepare for a hurricane.

Let’s break down that wording for a quick second.

Take a hurricane that has, for example, maximum sustained winds of 100 mph. If that hurricane’s maximum winds have strengthened to 100 mph over the last day or two, that storm is likely going to have considerably sharper impacts than one that’s weakened to 100 mph over the previous 24 hours or so.

That’s because a storm that is strengthening is more likely to pull down stronger winds that may be just above the surface.

“The primary reason for that is that a strengthening system typically has very intense and volatile convection, which readily and easily will create and mix down the stronger winds that are a little above the ground in a hurricane,” said Spectrum News meteorologist Matthew East, who is based in North Carolina.

In the earlier example, a strengthening storm can often mean whether or not someone at the surface actually experiences those estimated wind speeds and the wide-ranging impacts associated with them.

Now, you might know that the ring of clouds around the eye of a hurricane, known as the eyewall, is the strongest part of a storm.

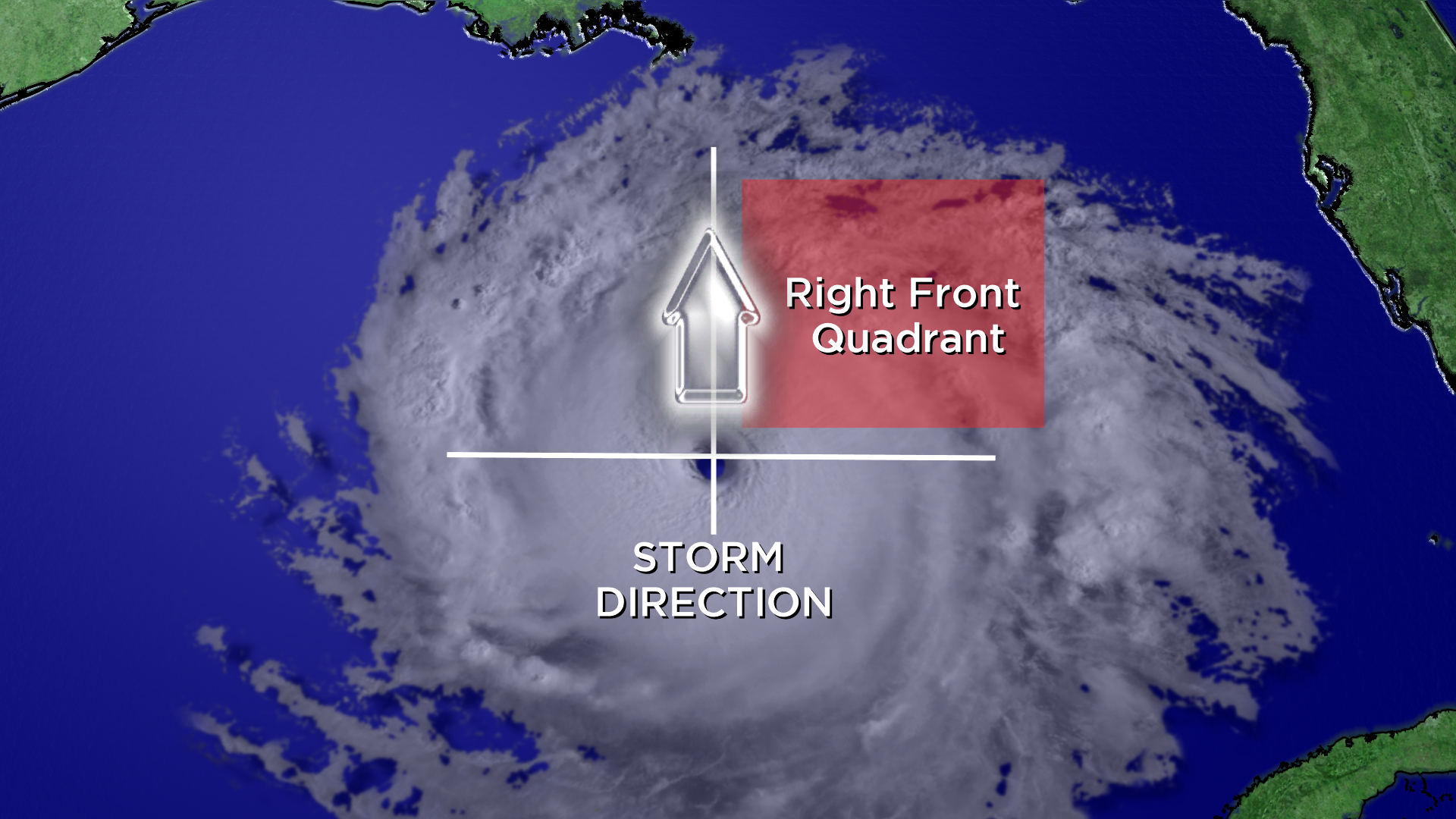

But, if you break down a hurricane into four quadrants, there’s one that’s considerably stronger than the rest of the storm.

The forward motion of a hurricane means that the so-called right front quadrant is usually the strongest quarter of a storm.

In the Northern Hemisphere, areas of low pressure, including hurricanes, move in a counter-clockwise direction. Because Atlantic hurricanes typically move from east to west, the storm’s forward motion creates an extra push on this part of a storm.

That means that the rotation and forward motion leads to the right front quadrant typically packing the strongest punch of any corner of a hurricane.

This is the part of the storm where tornadoes, the strongest winds, increased storm surge, and higher rainfall totals are the most likely.

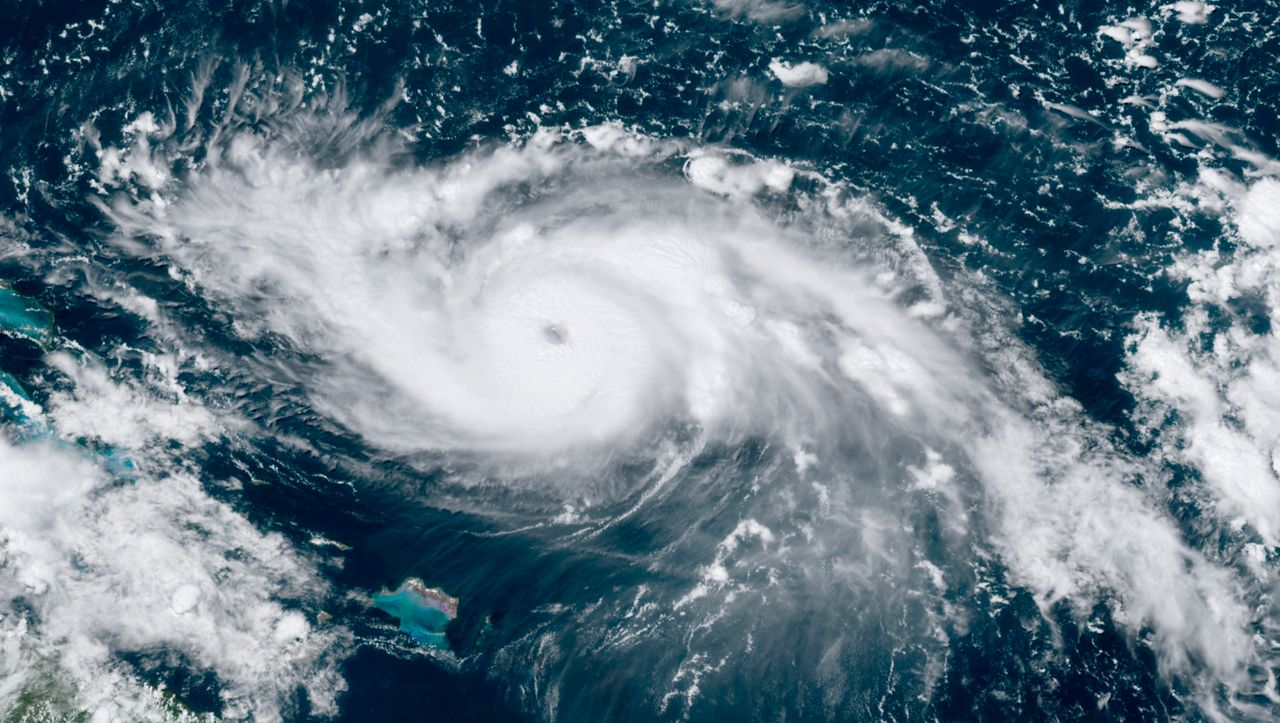

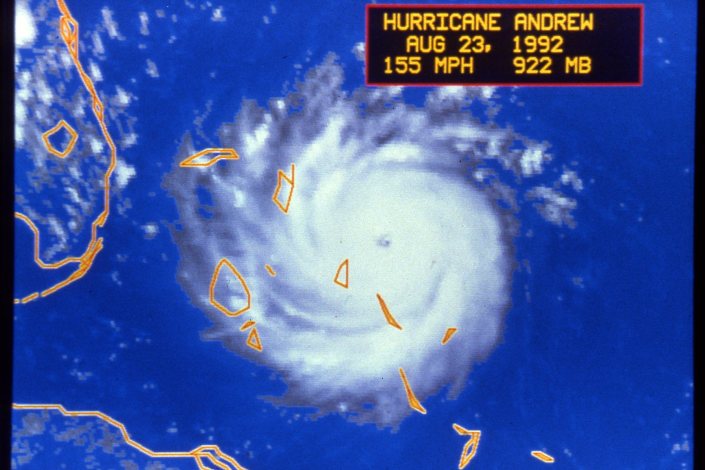

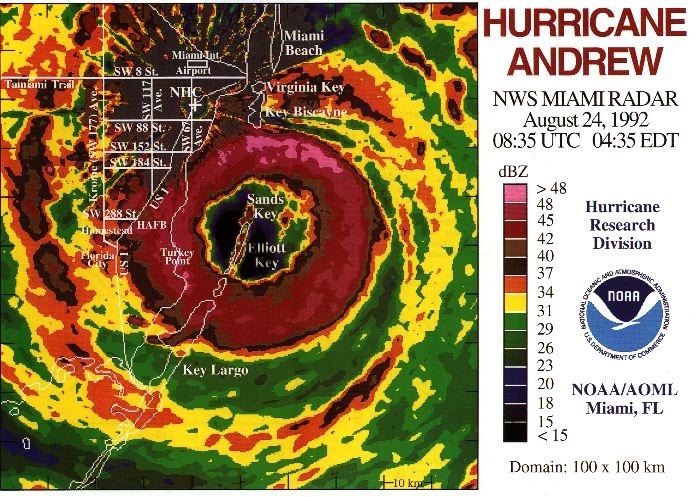

Normally, you might think that a bigger eyewall could mean a stronger storm. But with hurricanes, it’s the opposite.

If you’re looking at a hurricane on satellite and you see a tiny but clear eye, that’s typically an indicator of an extremely powerful storm. You’ll usually only see a so-called "pinhole eye" in a major hurricane (one of Category 3 or higher strength).

That can mean highly localized but devastating impacts for areas that feel the brunt of such an eyewall.

Take Hurricane Andrew in 1992, for example: that Category 5 storm’s small but intense eye meant the south side of Miami saw wind gusts up to 177 mph, while the north side of the city was mostly spared from Andrew’s worst effects.

Evacuation orders ahead of a hurricane are typically issued for areas right along the coast. That’s because the biggest concern for life and property during a hurricane is in association with storm surge.

While inland areas can also see strong winds and heavy rain during a hurricane–think Orlando in 2004 during Hurricane Charley–it’s water that’s usually the biggest killer in a hurricane.

That means if you head just a few miles inland from the coast, you’ve dramatically improved your odds of surviving the storm.

“Just get away from the surge,” said Spectrum News chief meteorologist Mike Clay.

This leads us to…

When you’re looking at how strong a hurricane might be, you’ll often take a look at a hurricane’s category on the Saffir-Simpson Scale or look at its maximum sustained winds.

But winds are far from the deadliest part of a hurricane–nor is it even close.

According to a 2014 National Hurricane Center study, only eight percent of U.S. hurricane fatalities between 1963 and 2012 was due to wind.

The largest proportion of hurricane deaths–by far–are due to storm surge. Storm surge accounted for about half (49 percent) of hurricane deaths over that study’s 50-year span. The next-closest cause of death, rain, and associated flooding caused an estimated 27 percent of U.S. hurricane deaths.

That means that water (flooding and storm surge combined) accounts for more than three-quarters of hurricane deaths, on average.

Of course, stronger winds fuel bigger ocean waves and increase storm surge, so maximum sustained winds and a storm’s Saffir-Simpson classification certainly matter.

But rather than the wind, it’s water that could prove deadly.