It was early September, and Sen. Chuck Schumer was in upstate New York for a big announcement.

The giant multinational company Siemens was unveiling plans for a first-of-its-kind high-speed rail production plant in the United States, bringing hundreds of jobs to the rural New York town of Horseheads, just outside of Elmira.

“We are going to be the center of rail car and high-speed rail car manufacturing in the whole country,” Schumer said, kicking off a press event alongside representatives from Siemens and the Brightline railroad.

Siemens’ decision to invest in the area was aided by the bipartisan infrastructure law that Schumer had ushered through the Senate just a few years before.

Within a matter of hours, Schumer was on a plane, rushing back to Washington for the swearing in of a new senator from New Jersey. Also on the to-do list: funding the government before a fast-approaching deadline.

This is Schumer’s juggling act - balancing the business of his Senate Majority Leader role with the pedestrian rituals of a local politician.

This year marks 25 years since Schumer first entered the U.S. Senate.

He is now the longest-serving U.S. senator in New York history, and the only New Yorker to serve as majority leader. It’s a role he long sought but is poised to lose if Republicans flip enough Senate seats in November.

'It just never stops'

Relentlessness has been a hallmark of Schumer’s political career — and a major reason for its durability.

Jim Kessler, who worked for the New York Democrat in both the House and the Senate, said Schumer is “not a workaholic.”

“He works harder than most workaholics,” Kessler said. “He's indefatigable. It just never stops.”

Even as he has risen to the pinnacle of power, Schumer still visits each of New York’s 62 counties every year, continuing a tradition he began when first entering the Senate.

Speaking to Spectrum News in a rare one-on-one interview, Schumer said, “If anything, I've been persistent in just about everything I've done. And what I have found is, usually it pays off.”

The path to the U.S. Senate

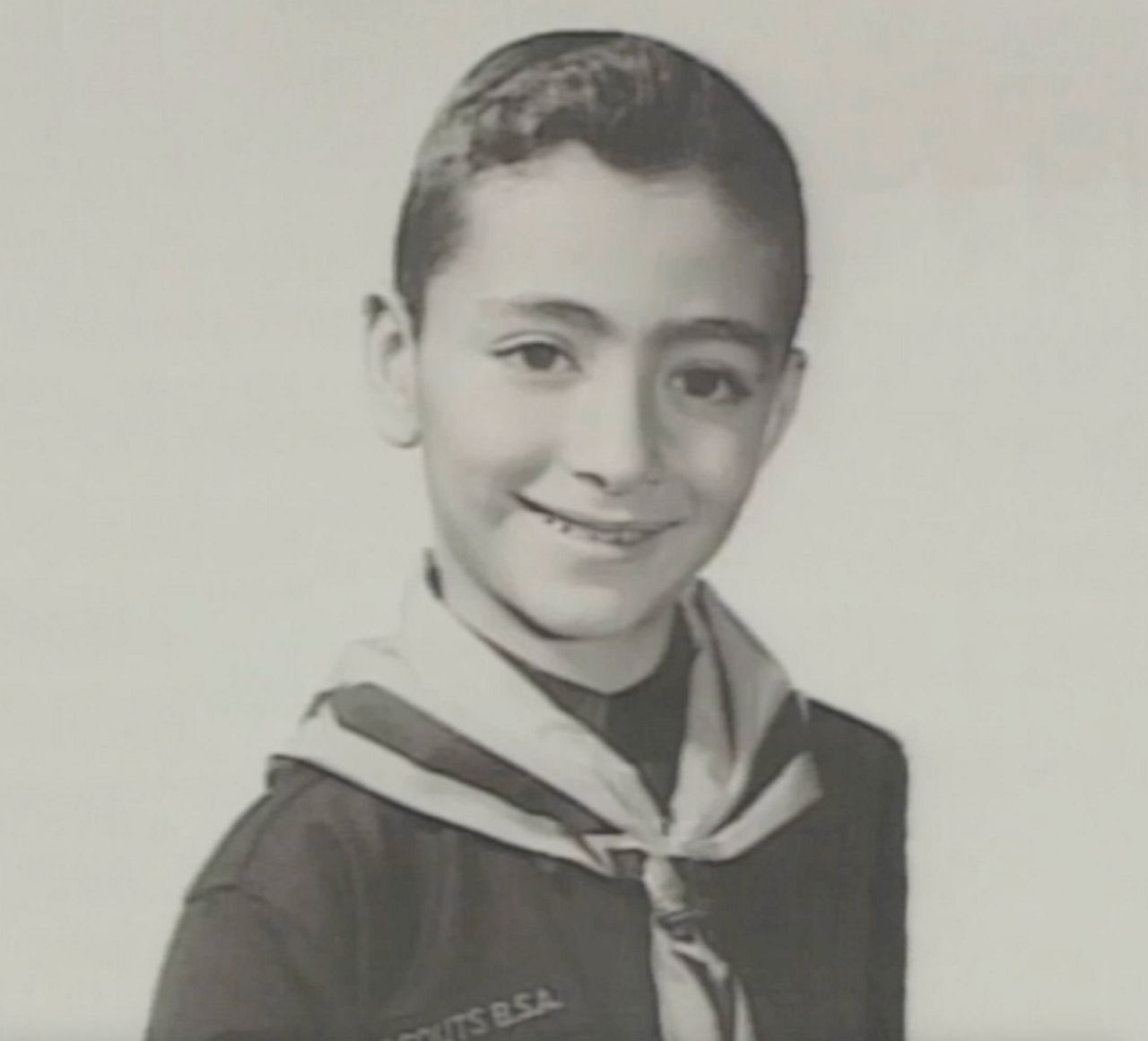

Schumer was born in Brooklyn, the son of an exterminator and a homemaker.

Fresh out of Harvard Law School, he was elected to the New York State Assembly at age 23 — the youngest person to do that since Teddy Roosevelt.

He moved on to Congress in 1981, representing Brooklyn in the U.S. House for 18 years. He gained notice for passing legislation like the Brady Bill, which required background checks for most gun purchases.

Speaking on the House floor at the time, he told his colleagues, “We’re all frightened for our children. We’re disgusted by this orgy of handgun slaughter.”

After Republicans took control of the House in 1995, sending Democrats into the minority, a frustrated Schumer set his sights higher.

“I have been: majority Senate, minority Senate, majority House, minority House. Only one really sucks. So I left the House to go to the Senate,” he said, reflecting back on his career.

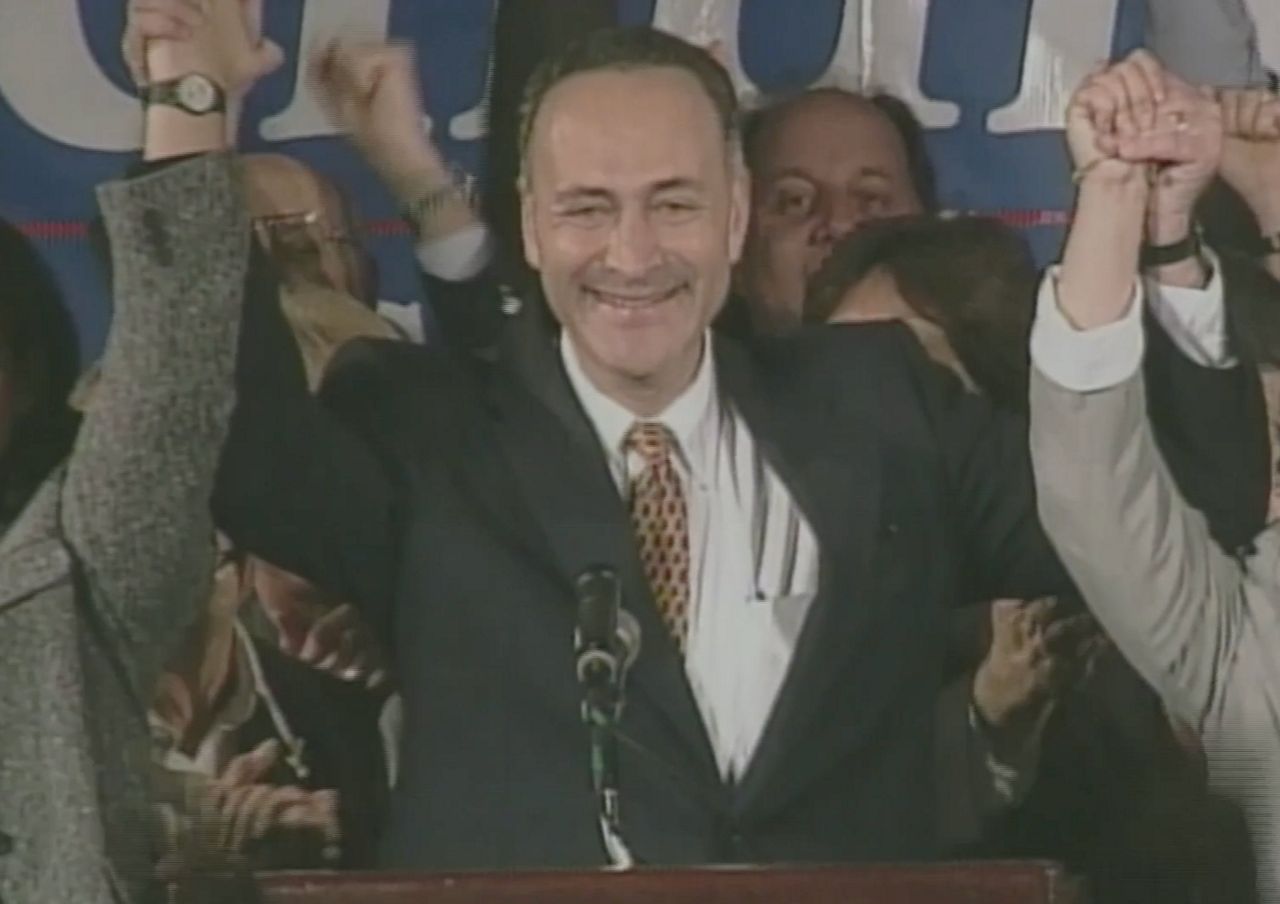

But to get to the U.S. Senate, he had to defeat two New York institutions in the 1998 election.

First up was former Rep. Geraldine Ferraro, who was also vying for the Democratic nomination.

It was a three-way race. All three candidates, including Schumer, had ties to downstate. To win, Kessler said, Schumer looked north.

“Schumer said, ‘I'm going to spend so much time and I'm going to spend a lot of money upstate, that I will win in the other parts of the state that have far fewer Democratic votes in a Democratic primary, but it will be enough for me to win,’” Kessler said.

The strategy worked.

Next up was incumbent Sen. Alfonse D’Amato, who was wrapping up his third term in the upper chamber. He had gained the nickname “Sen. Pothole” because of his work constituent services.

“[It] would have been easier to run against anybody,” D’Amato told Spectrum News. “Schumer works as hard, if not harder, than anybody. He's bright. He's articulate.”

To counter D’Amato, Schumer deployed what would become a staple of his politics: Talking kitchen-table and consumer issues in hopes of appealing to a hypothetical middle-class family he dubbed the “Baileys.”

“They want to be taken seriously. They are not that partisan. They want to make sure you care about what they care about,” Schumer said, explaining the Baileys as much as his own electoral philosophy. “Show them some respect and realize that they just want a better life for themselves and their kids.”

Schumer campaigned as a centrist Democrat and relentlessly stumped upstate, betting he could narrow the Republican advantage in their traditional stronghold.

Schumer defeated D’Amato with nearly 55 percent of the vote, redefining how a Democrat could win in the state.

Rising through the ranks

Once Schumer arrived in the upper chamber, Sen. Harry Reid of Nevada, who became Democratic Leader in 2005, took him under his wing.

Ahead of the 2006 election, Reid named Schumer chair of the Senate Democrats’ campaign arm. He stayed on in the role for the 2008 election, too. Democrats picked up seats both cycles.

“Harry Reid recognized Chuck's skill and Chuck's uncanny ability to communicate otherwise arcane policy into sort of common-sense, meat-and-potatoes messaging that people understood and could connect with,” said Mike Morey, a former Schumer aide.

That uncanny ability to communicate, coupled with a driving ambition, played out in different ways.

As he worked his way up the political ladder in New York, Schumer routinely scheduled news conferences, often focused on consumer issues, for every Sunday - sensing, correctly, that media outlets were starved for stories on a normally slow news day.

On Capitol Hill, Sen. Bob Dole first uttered what would become a cliche: The most dangerous place in Washington is between Schumer and a camera.

'It’s Raining Men'

Former aides say Schumer could be demanding and hard-charging, but also willing to hear their ideas. Funny. Even quirky.

One of his songs of choice, a former aide said, is "It's Raining Men." Asked to explain why, Schumer said, “I just love the song.”

“We have a little party every year. We call it ‘Christmas in Schumer-land.’ And I have led the staff dancing around with turning the umbrellas upside down — that’s the lyrics to the song,” he said. “It’s a tradition.”

Retired California Sen. Barbara Boxer worked alongside Schumer in the Senate for nearly two decades.

“Chuck is one of the smartest people I know. He's very, very bright. It's disarming because he's also very funny, and he's self-deprecating,” she said. “It takes a while to get him because of all that.”

The alumni network of former Schumer aides is large, stretching to many corners of Washington and beyond.

“He's the only man that crashed my bridal shower. In Brooklyn. He rode his bike over,” said Polly Trottenberg, who once worked as Schumer’s legislative director. She now serves as deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

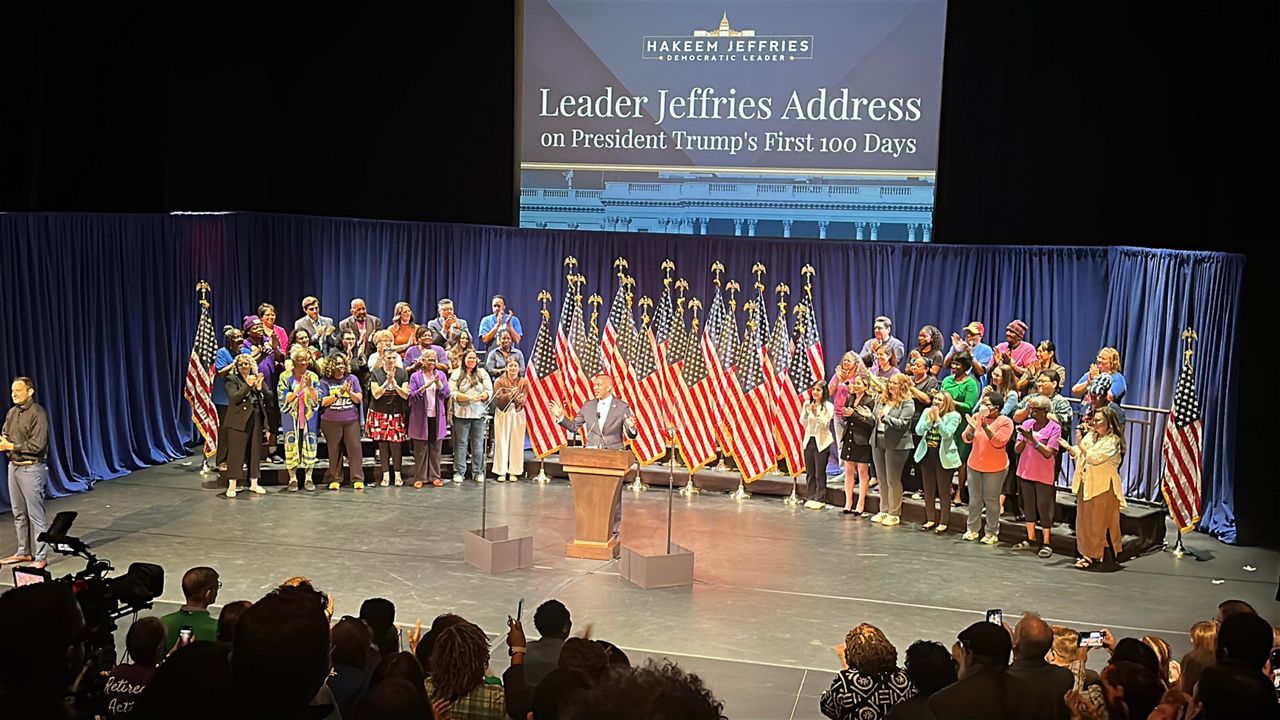

Becoming majority leader

In 2016, ahead of Reid’s approaching retirement, Schumer’s Democratic colleagues elected him as their new leader.

And in 2021, after Democrats picked up a few more Senate seats, he ascended to the job he long sought: majority leader.

In addition to becoming the first New Yorker to hold the position, he also was the first Jewish person to do so.

“If you were to ask someone about Chuck Schumer in 1998, they would probably describe to you: ambitious, sharp-elbowed New Yorker really working his way to be noticed, be seen, centered on himself,” Morey said.

“If you asked anyone about who Chuck Schumer is today, they would tell you that he is the same level of energy around accomplishment, but with a much more sophisticated and accomplished worldview around the way you get that done,” he continued.

With the new job came new power - power Schumer would wield to pass big national legislation that would touch communities back home.

This is the first part of a three-part series profiling Sen. Chuck Schumer as he marks 25 years in the U.S. Senate. Part two, examining what he’s gotten done for New York, can be found here. Part three, evaluating his leadership style as Senate majority leader, can be found here.

)