Millions of calls come through a 911 call center every year, and tens of thousands of them are for a mental health emergency.

A tiny fraction of them reach Isha Middleton.

What You Need To Know

- B-HEARD launched in 2021 in several police precincts in Manhattan

- It's now in 31 precincts across the city

- But some advocates and officials say it's failing to meet expectations

Middleton is on a B-HEARD team — a group of mental health professionals and EMTs who respond to nonviolent 911 mental health calls — a pilot program launched in 2021 aimed at reducing police responses to mental health emergencies.

“We had an opportunity to be, instead of hands-on, minds-on. There are more people that need help mentally than they do physically,” Middleton said.

They’re a small team. Tsering Wangmo is a social worker on it.

“Sometimes when you see a bunch of us in uniform with radio and ambulance, it scares people, and we tell them the whole purpose of why we’re there,” Wangmo said. “We tell them we’re here to help you, you’re not in trouble. And that helps a lot.”

After the shooting of Win Rozario in Queens, a 19-year-old shot and killed in March by police during an apparent mental health crisis, officials and advocates are examining how the city responds to mental health emergencies.

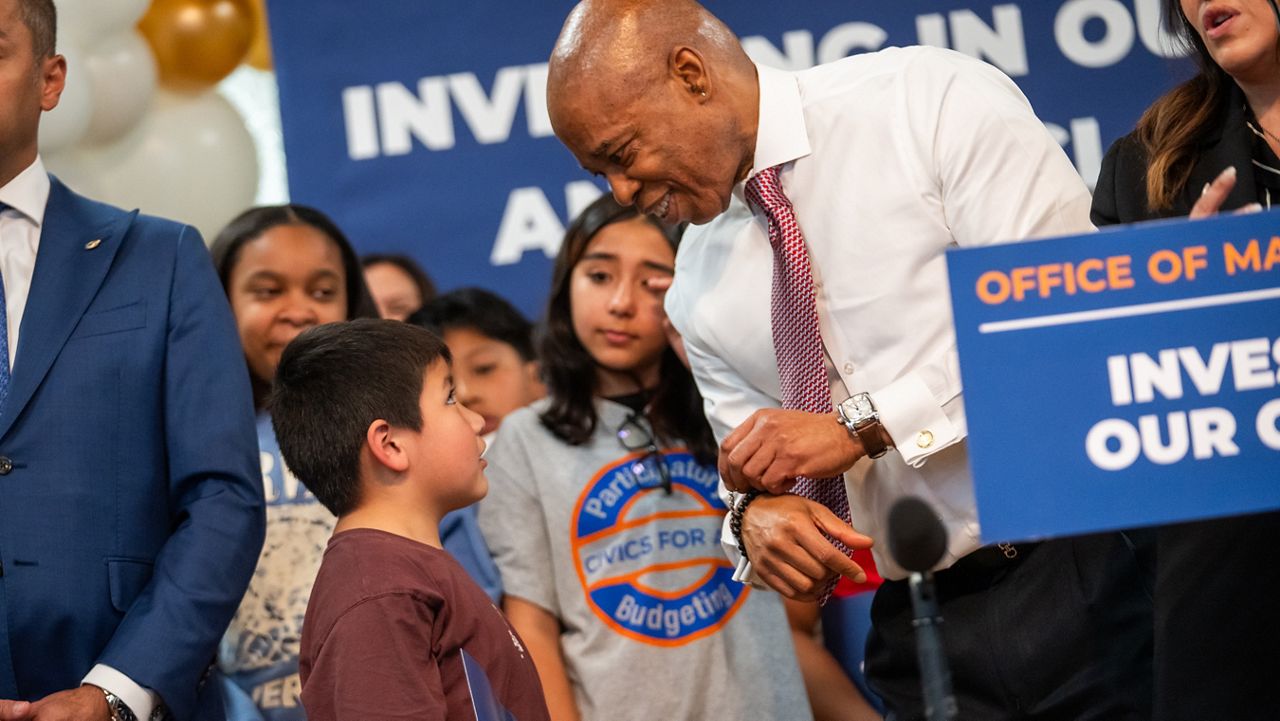

“Every single time a B-HEARD team responds to someone having a mental health crisis or a mental health emergency, we’re sending a mental health professional to that person for the first time in our city’s history,” Laquisha Grant, with the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health, said.

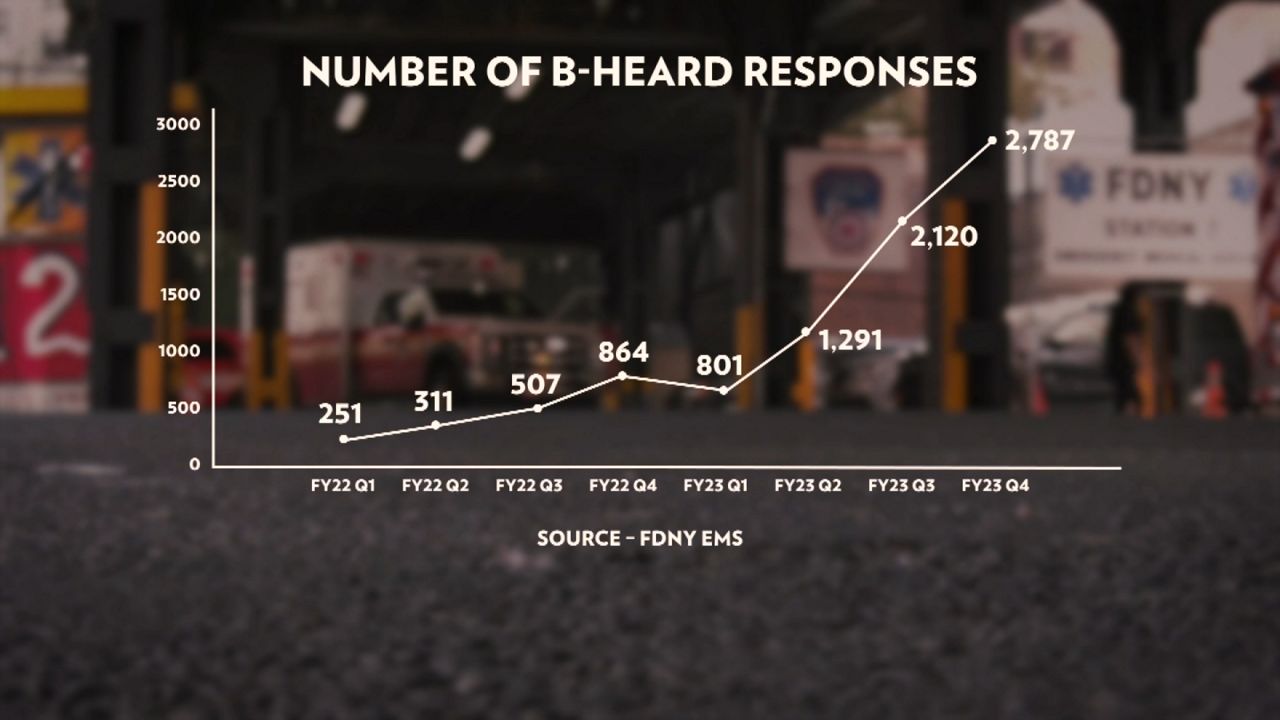

Almost three years into the pilot program, NY1 has found B-HEARD has not reached its original goals, and a planned expansion is on pause.

When first announced, the goal was to cover half of the city’s mental health calls in the pilot area.

The number of calls it responds to every quarter is still quite small, and, according to the latest data from the program, which is from last summer, it only responded to 23% of calls in its coverage area.

“The goal was, yeah, a bit premature,” Grant said in an exclusive interview with NY1. “And we just learned so much operating the program.”

NY1 asked if there was a goal now.

“The goal is to reduce unnecessary police responses,” she said. “It’s to reduce unnecessary transports and to route as many calls as possible to the teams.”

At one point, city officials put more promise in the program.

In early 2023, Mayor Eric Adams said he’d bring it to every police precinct in the city. But eight months later, the city paused the expansion. It’s unclear when or if that will change.

“As of right now we have paused expansion partially due to budget cuts, but this has allowed us an opportunity to really figure out what citywide expansion will look like, and given us an opportunity to really make improvements to the program,” Grant said.

For now, B-HEARD operates in just 31 of the 77 police precincts, covering the Bronx and parts of Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens.

It does not operate in the precinct where Rozario was killed. Officials said his call was not eligible for the program because the operator classified it as a drug call.

For years, families, like Peggy Herrera’s, have called for an alternative response to mental health — other than police. She called 911 in 2019 for her son, who she said had mental health issues.

“He started to break stuff in his room,” she said. “So I just walked out quietly and called the ambulance. And calling the ambulance, I spent the night in jail.”

When police came, they tried to coax her son, Justin Baerga, out of the apartment. Body camera footage shows Herrera would not let police break the door to get her son.

A fight ensued, and she was arrested. Police brought her son to the ground.

“Uniforms only escalate someone in a crisis,” Herrera said. “And they come with a stigma. We need compassion. We don’t need uniforms.”

Baerga died in 2022 in a shooting in Queens. Prior to that, he had been the lead plaintiff in a class action lawsuit to get police out of mental health calls.

Ruth Lowenkron is one of the lawyers leading that case.

“I want to be clear, it’s that the wrong people are being sent,” Ruth Lowenkron, with New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, said. “So, the city has to have a system in place whereby they send people who are the appropriate responders to mental health crises.”

Lowenkron says B-HEARD is a start, but it’s not nearly enough. Police are still responding to mental health emergencies.

“We go there and [if] there is a patient we can help, we can tell PD we are OK,” EMT Dannalee Chambers said. “Cause a lot of people are uncomfortable with the cops around, and they’re more open to us when it’s just us, and they don’t feel like they’re in trouble.”

So for now, Chambers’ EMT team will handle about three to five calls a day. The rest may be police.