President Joe Biden, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, and other members of congressional leadership are set to sit down Tuesday at the White House to discuss the debt limit, also known as the debt ceiling, an important aspect of the economy that can be difficult to grasp.

If the United States defaults on its debts, the results could be catastrophic for the country and the global economy, experts say. With Republicans and Democrats standing their ground on how they want to approach the issue, the risk of defaulting for the first time in U.S. history is all too real.

But what is the debt limit? What would it mean if the country defaults on its debts? What does each side want? Here’s a few things you need to know about the debt limit:

What is the debt limit?

For decades, the United States has been spending more than it collects in taxes, effectively using its credit card to buy things and pay its bills to the tune of $31.46 trillion, as of May 8.

“The debt limit is the total amount of money that the United States government is authorized to borrow to meet its existing legal obligations, including Social Security and Medicare benefits, military salaries, interest on the national debt, tax refunds, and other payments,” according to the U.S. Department of Treasury.

Meaning, there’s only a certain amount of money the government can borrow before a limit, set by Congress, kicks in and the country can’t take on anymore debt. In order to keep taking on debt, Congress will have to raise the limit.

Why do we have a debt limit?

The U.S. Constitution gives the power to borrow money to Congress, which in turn gave permission to the executive branch to borrow money in certain circumstances throughout the country’s history, including for the construction of the Panama Canal and to fund foreign wars, according to the Congressional Research Service.

While limits on certain debts were implemented throughout World War I and the Great Depression, Congress set the first overall debt limit at $45 billion in 1939, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a think tank.

The goal was to allow the U.S. government to fund itself, particularly in times of great need, without having to repeatedly go back to Congress for permission. But as the debt has risen in all but a few years since World War II, Congress has had to approve a debt limit increase 102 times.

When will the country run out of money?

The debt ceiling is technically about $31.38 trillion, which the U.S. surpassed in January, but Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen took what she’s called “extraordinary measures” to prevent a default. These measures essentially shift money around by, for example, temporarily suspending investments in government workers’ savings plans and health plans for retired postal workers, among other accounting tricks. The plans will then be made whole once the debt limit is increased, Yellen said.

The measures are a stopgap, however. In order to avoid a default on the debt, Congress will have to raise the limit or suspend it entirely in the coming months and possibly as soon as June 1, Yellen said last week. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated the country would run out of time in “early June,” while earlier estimates from financial institutions like Goldman Sachs placed the doomsday date at some point this summer.

Has the United States ever defaulted on its debts?

Technically, yes, but by accident and only once in 1979, which was blamed on an unintentional error.

Otherwise, no, the country has never intentionally defaulted on its debts. Since 1960, the debt ceiling has been raised, temporarily extended or revised 78 times, including 49 times under Republican presidents and 29 times under Democratic presidents, according to the Treasury Department.

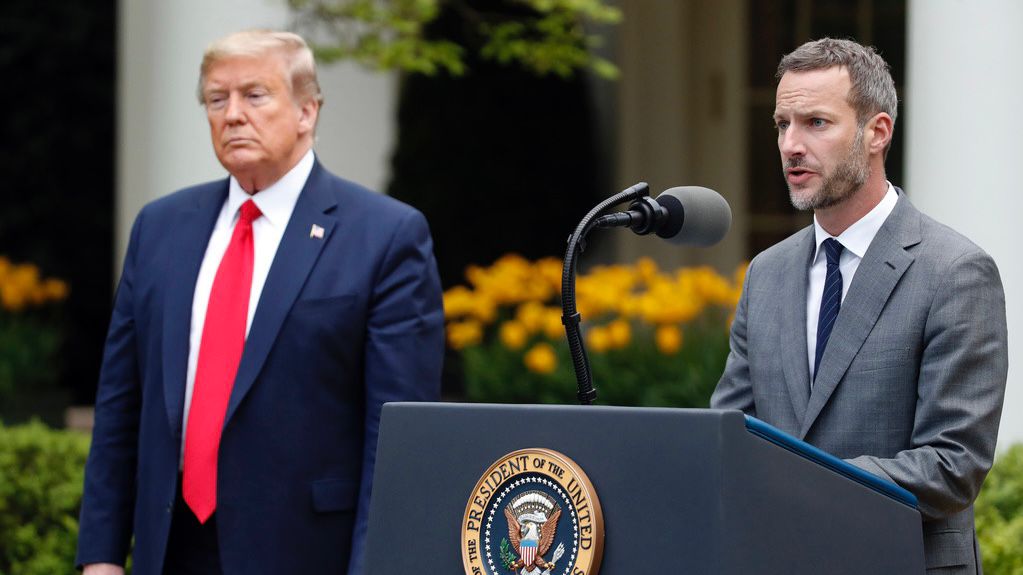

The White House has noted the debt ceiling was increased three times under President Donald Trump without conditions, something Biden and the Democrats want again. Congressional Republicans are now calling for spending cuts in exchange for a debt ceiling increase.

What happens if the United States defaults on its debts?

The short answer is: no one knows specifically, but experts warn it would be catastrophic.

“Say you qualify for Social Security, you want to go to the Social Security office and get your Social Security benefits, it’s not clear to me that they will be open and there will be anyone there to man them,” Bill Hoagland, a senior vice president for the Bipartisan Policy Center, told Spectrum News last week.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget said a default “would roil global financial markets and create chaos, since both domestic and international markets depend on the relative economic and political stability of U.S. debt.”

“If they have a 401(k) retirement plan, or something of that nature, they'll feel it immediately,” Hoagland added.

The White House’s Council of Economic Advisers projects a protracted default could lead to the loss of 8.3 million jobs and a 5% increase in unemployment. Even if the debt ceiling negotiations were to go down to the wire, hundreds of thousands of jobs could be lost, Biden administration economists predict.

Internationally, American debt, long seen as a safe bet, would become a less desirable investment due to the country’s political dysfunction and financial mismanagement.

“Even if resolved quickly, Americans would likely pay for this default for generations, as global investors would rightly believe that the federal government’s finances have been politicized and that a time may come when they would not be paid what they are owed when owed it,” wrote Mark Zandi, the chief economist for financial services giant Moody’s Analytics, in testimony to the Senate in March.

What's the difference between a debt default and a government shutdown?

A debt default would mean the U.S. government would no longer be able to take on debt and would be stuck using what little funding it has available to pay down its bills for past spending, while others would go unpaid. Everything from Social Security payments to food stamps to federal civilian and military employee paychecks could be delayed.

A government shutdown is when Congress doesn’t authorize new future spending and nonessential government services are paused until a new budget is passed.

What do Democrats want?

Democrats, who control the White House and the Senate, want a “clean” debt ceiling increase — an increase without conditions, like spending cuts the Republicans are asking for. They see the issue as too risky to debate over and would rather negotiate over spending when they hash out the next budget later this year.

What do Republicans want?

House Republicans narrowly passed a bill last month that would raise the debt ceiling by $1.5 trillion in exchange for spending cuts to 2022 budget levels and a cap on future spending increases at 1% over the next decade. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the bill would reduce the budget deficit by $4.8 trillion in 10 years.

The bill includes more work requirements for recipients of food stamps and government aid, an end to renewable energy tax breaks signed into law last year, and halt Biden’s student debt forgiveness plan.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., has called the bill “dead on arrival” in the Senate, but don’t expect him to get any help from his Republican colleagues: 43 of them, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., signed onto a letter over the weekend saying they will oppose raising the debt ceiling without spending cuts.

Where do negotiations stand?

There has been little public optimism for a quick resolution even with Biden and McCarthy set to sit down with Schumer, McConnell, and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y., on Tuesday.

“We should not be holding the U.S. economy hostage to next year's budget process. We should make sure that the United States is not a deadbeat nation, as the president says, do a clean increase in the debt ceiling, and then have those conversations about future spending,” White House economist Heather Boushey told Spectrum News on Monday.

Both sides have been at odds for months now and have stood firm on their positions, with the White House continuing to insist they won’t negotiate over the debt ceiling. But it’s possible Biden informally concedes to some spending cuts in the budget later in exchange for a clean increase first, a deal both parties could sell as a win.

What do alternative solutions look like?

If neither side gets their way or a deal can’t be reached, other options have been considered by policymakers, though none are particularly likely.

One option is just to ignore the debt limit and continue borrowing. Advocates see a path forward thanks to the 14th Amendment, which states, in part “the validity of the public debt of the United States… shall not be questioned.” Biden said last week he wasn’t considering it yet and Yellen said Sunday the idea could cause a “constitutional crisis.”

Another possible, though still unlikely, option is a plan House Democrats quietly began developing back in January. A bill that would increase the debt ceiling without conditions was introduced then by a low-profile member of the House. Through legislative maneuvering, Democrats in the minority could bring it to the floor for a vote without approval by McCarthy.

If Democrats could get 218 members of Congress to sign what is known as a “discharge petition,” the bill would come up for a vote, but they would need at least five House Republicans to sign on. Even more moderate Republicans have shown little sign of budging.

What is the trillion dollar coin?

Technically the U.S. Treasury has the authority to mint platinum coins of any denomination. Proponents of the idea argue the U.S. Mint could simply create a $1 trillion coin and deposit it with the Federal Reserve, which functions as the government’s banker. Then, the nation’s bills could keep getting paid.

Yellen is not a fan of the trillion dollar coin. She called it a “gimmick” and said the Federal Reserve was not obligated to accept the coin as a deposit.

Who does the United States owe money to?

According to the Pew Research Center, U.S. debt might be the most widely held financial security on the planet. As of Sept. 2022, nearly 60% of the U.S. debt was held by public investors, meaning individuals, investment funds and foreign governments, Pew determined. At any given time, roughly a third of the public investment is held by foreign entities, including governments, according to a May 2022 report from the Congressional Research Service, which named the governments of Japan, China, and the United Kingdom as the top holders of U.S. debt at the time.

The other 40% is money the U.S. government owes itself in one form or the other, according to Pew. About 20% of the total debt is held by the Federal Reserve, just over 9% is owed to Social Security, roughly 4% is owed to the military’s retirement fund and another 3% is owed to the civil service’s retirement and disability fund.

Annually, the U.S. spends about 12% of its budget, or $384 billion as of March 2023, paying the interest on these loans, according to the Treasury Department.

Spectrum News’ Cassie Semyon and Kevin Frey contributed to this report.

_crop)