Winter break is over, which means politicos are starting to eye the April 1 New York state budget deadline. But don’t jump ahead too quickly. There are still a few items to check off the to-do list before any serious horse trading begins.

Tuesday is the scheduled “Economic & Revenue Consensus Forecasting Conference Meeting," which is a gathering of the Legislature’s financial leadership. Members of both majorities and the minorities of each house will attend, as well as the state budget director and the state comptroller. The assembled will hear from several economists, and before March, determine how much the state will have to spend over the next year.

Not that the parties come to any precise agreement.

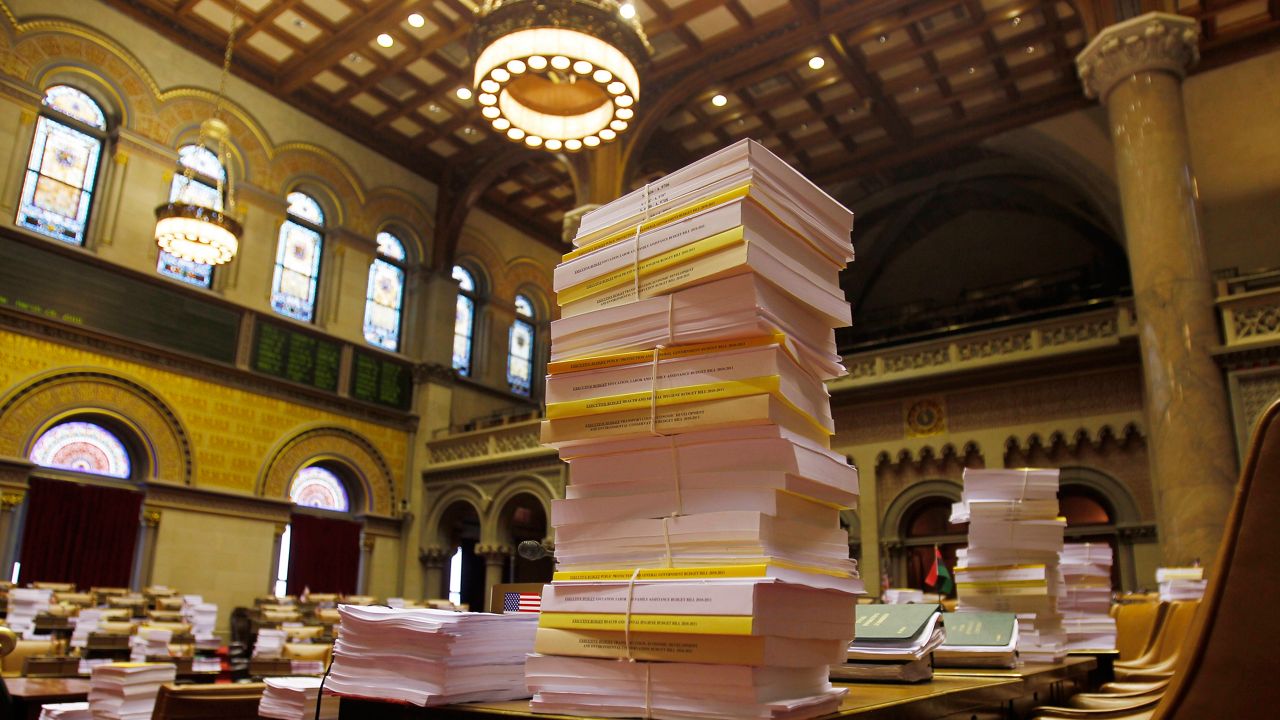

Once they have general spending guidelines in place, lawmakers will use the governor’s executive budget as a template from which to build their own budgets. These are called one-house budget bills because they reflect the priorities of each house. According to both the Assembly and Senate majorities, one-house budgets will be released the week of March 13.

It’s at this point that negotiations get down and dirty.

While there is much for the Legislature to like in Hochul’s proposal, including full funding of Foundation Aid for schools and the largest state contribution to the Medicaid budget ever, according to lobbyist Jack O’Donnell of O’Donnell & Associates, the governor’s budget sets up showdowns with the Assembly and Senate on:

- education (lifting the charter cap)

- housing (support for a new 421-a and a proposal to allow Albany to override local zoning)

- Medicaid (the pharmacy carve out)

- local governments (cutting enhanced Medicaid)

“The LOB and district offices are full of constituents advocating on these and other issues while Gov. Hochul comes into the budget process with the upper hand in negotiations and her own determination so don’t make any travel plans in April,” O’Donnell cautioned.

Here are 4 things that you should watch for:

Will the budget raise taxes on the wealthiest New Yorkers?

It’s a perpetual question in Albany. This year, Gov. Hochul has, on one hand, said she would not increase personal income taxes on the state’s wealthiest New Yorkers. On the other, she has proposed hiking the cigarette tax. She’s also pushing for an MTA Payroll tax which is viewed by many as an additional cost on small business and workers.

An argument can be made that the state doesn’t need to raise taxes – and it was made by E.J. McMahon, founding senior fellow of the Empire Center for Public Policy, during testimony before the Joint Legislative Fiscal Committee.

“New York’s revenues quickly recovered from the pandemic because the state government does, in fact, ‘tax the rich’ to a far greater extent than almost any other state. However, there are clear signs that the state’s heavy reliance on its highest earners, already at record levels before 2020, is both unstable and unsustainable,” McMahon stated.

Indeed, the governor is so comfortable with the state’s finances that she has proposed socking away about $8 billion into a rainy-day fund, while predicting a three-year-long recession.

It’s a position that a coalition of groups and some lawmakers take issue with.

“There are no budget gaps on the horizon,” said Michael Kink of Strong Economy for All Coalition, which is a part of the Invest in Our NY Coalition. “The only budget gaps in her financial plan are created by her assumption that we are going to have a three-year long recession.”

The companion “Invest In Our New York Act” includes several pieces of legislation that would raise $40 billion in new public funds by hiking taxes exclusively on the wealthiest people and corporations. The bills include a progressive corporate tax as well as a proposed state capital gains tax.

“I think the Legislature will take some of those reserves that she’s proposing, to spend on things like building affordable housing…a more robust transition on climate and affordable clean energy. And, potentially, to support the public cost of things like Medicaid and things like the minimum wage,” Kink told Capital Tonight.

How will the minimum wage be hiked?

This is an area where there is substantial agreement, and not just among lawmakers.

The latest Siena College poll shows that by 70% to 26%, voters, including 59% of Republican voters, support the governor’s idea of tying minimum-wage hike to inflation.

But there are details in the governor’s proposal that progressives want to do away with.

“She has this quote-unquote indexing proposal that’s not in any way meeting cost of living needs. It locks in a poverty-level wage. A $15 wage with bad inflation has been eroded to about $12.50,” Kink said.

Hochul’s minimum wage proposal also comes with a 3% cap, and off-ramps in case of an economic downturn.

“My conception of indexing for inflation is indexing for inflation. Like, if there’s 5% inflation, you get a 5% increase in wages,” Kink said.

According to Blair Horner, executive director of the New York Public Interest Group (NYPIRG), the only question seems to be the flavor of minimum wage hike the legislature prefers.

“I think on the minimum wage, there seems to be a growing consensus to increase it,” said Horner. “Whether or not they follow the governor’s proposal, or the Legislature raises the floor first, I think that’s the only relevant question.”

One key legislative proposal is a “Raise the Wage” bill sponsored by Sen. Jessica Ramos and Assemblymember Latoya Joyner. It would increase the state’s minimum wage and index it to inflation and worker productivity within five years, according to Russell Weaver of Cornell.

If the Legislature decides to link the wage to inflation the way that Ramos and Joyner are proposing, there will be some additional public costs in areas including Medicaid and home care.

There are other arguments as well against a minimum wage hike coming so soon after the state’s other, recent increases. As the New York Post states, “New York’s already facing an exodus of residents and businesses, and progressives only want to speed up the departures.”

Will localities catch a break?

If there are any real losers in Hochul’s otherwise generous spending plan, it’s got to be the state’s localities.

There are three issues confronting them: Cities, towns and villages will, for the 14th year in a row, see flat AIM (Aid & Incentives for Municipalities) Aid. Hochul is proposing to override local zoning to accomplish her vision of building 800,000 new housing units over 10 years. And the final insult, according to counties, is her proposal to shift millions of new Medicaid costs to counties.

“It is difficult to fathom that an executive budget with a $7 billion increase in spending, proposed by a governor with an oft-stated strong belief in local governments, fails to invest one additional dime in our cities, villages, counties and towns,” Peter Baynes, executive director of the New York Conference of Mayors wrote in a statement dated Feb. 7.

Baynes is proposing a completely new funding stream for localities tentatively called “Municipal Operation Aid” (MOA), which is tied to the services they provide and the number of residents they serve. NYCOM is asking for $100 million for the new funding.

On local zoning, Onondaga County Executive Ryan McMahon argues that while larger communities may not have problems meeting Hochul’s housing targets, rural areas likely will.

“For many of my towns, especially in my rural communities, to meet any goal with this, you’re going to have to expand services, which the county controls, right? We control all the sewers and the wastewater system,” McMahon said. “I have questions regarding who is going to pay for that sewer expansion.”

Members of the New York State Association of Counties (NYSAC), which is holding its legislative conference this week, were not shy in expressing how they feel about Hochul’s decision to cost-shift Medicaid costs onto counties.

“The governor is looking to intercept almost $300 million in federal funds earmarked for local taxpayers,” said Stephen Acquario, NYSAC’s executive director.

According to NYPIRG’s Blair Horner, localities are easier to target than “political King Kongs” like unions.

“The power of politics is not the same with local governments as it is with, say, unions, or businesses or other advocacy groups,” said Horner. “They are creatures of the state.”

How will New York fund the climate transition?

Ever since Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA) in July 2019, lawmakers have been aware that the time would eventually come when the state’s commitment to lowering greenhouse gas emissions would need to be supported by a hefty public investment.

That time has come.

“There’s definitely a big need to fund the transition,” Conor Brambrick, director of policy at Environmental Advocates NY, told Capital Tonight. “NYSERDA and the Climate Action Council, when they did their analysis, identified a need of an additional $10 billion of spending year over year if we’re going to meet the mandates of the climate law.”

While that’s not necessarily all state money, a hefty portion of it is.

“Thinking of how we’re going to pay for all these things. I think it’s really going to be a combination of what is the government doing directly, and where are they providing incentives and carrots and sticks for private sector dollars to be directed,” said Julie Tighe, president of the New York League of Conservation Voters. “The governor certainly started off with a lightly detailed but strong concept of a Cap & Invest program.”

Gov. Hochul adopted Cap & Invest directly from the Climate Action Council’s scoping plan, and incorporated it into her executive budget.

“That, for what it’s worth, is the vehicle that everyone is looking at, in terms of generating funds,” EANY’s Brambrick explained.

Cap & Invest has the potential to raise billions of dollars, but after seeing how it has played out in other states, including California, EANY is advocating for guardrails that would ensure disadvantaged communities would be protected.

“We would have preferred a…fee or tax on polluters. Cap & Invest will function that way, but it doesn’t offer the price stability. Under a tax or fee option, the state can decide exactly how much money it’s raising. Under Cap & Invest, the prices will fluctuate based on the market,” Bambrick said. “But we are supportive of the concept.”

Tighe is supportive of Cap & Invest, but like Bambrick, is looking for more detail.

“I think it’s a really strong start, having this conceptually out there. It’s clear we need a lot more details on how they would implement that program,” Tighe said.

Under Hochul’s plan, 33% of the funds raised by Cap & Invest would go to households and businesses to offset a potential increase in energy costs. The other 66% is open-ended.

Bambrick and Tighe are also watching a selection of other bills that will support Cap & Invest.

For example, EANY is backing a bill called the “Climate and Community Protection Fund” (CCPF). While it has yet to be introduced, it will likely be sponsored by Sen. Pete Harkham. It is modeled on the Environmental Protection Fund. The CCPF would create a dedicated revenue stream for a variety of programs including large scale transmission distribution projects or smaller programs like heat pump assistance.

Tighe is closely watching a bill being carried by Sen. Liz Krueger called the New York Heat Bill that would eliminate some of the obligations that bind utilities to provide certain fuels. She is also advocating for a statewide clean fuel standard.

“We need a clean fuel standard that sets specific reductions for the transportation sector,” Tighe said.

On the other end of the political spectrum are some Republicans who think the governor is simply spending too much.

“How much more are the majorities going to add when it’s all said and done? New Yorkers came out of COVID shutdowns straight into record-high inflation. Common sense says that this year’s budget can’t impose more costs on residents, localities and businesses,” Assembly Minority Leader Will Barclay said to Capital Tonight. “But that’s where things seem to be headed.”