Step into Ian Martin’s home, and his love for New York City is evident. There’s even a ‘New Yorker’ poster hanging on the hall.

“I love the people, that’s why it was so awesome to work for them,” Martin said.

For three years, Martin worked for New Yorkers, serving as the deputy press secretary for the Department of Social Services.

“Everything from homelessness to supportive housing to food stamps and Medicaid,” said Martin.

But in February, six weeks after Mayor Eric Adams took office, he quit, and says his main reason for doing do was the city’s return-to-office mandate.

“On the campaign trail, Adams had actually said he was going to think about doing some sort of hybrid schedule, but within the first few weeks of him on the job, it was pretty apparent that that was not the case,” said Martin.

Martin is just one of thousands of municipal workers who have left since the in-person mandate took effect Sept. 13, 2021.

Numbers from the NYC Independent Budget Office, or IBO, show the city’s vacancy rate this June climbed to 7.9%.

In January 2020 it was 1.6%.

The vacancy rate is determined by comparing the city’s budgeted headcount with the actual headcount.

While the budgeted headcount has rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, the actual number of city workers continues to drop.

There was an especially sharp decline in October 2021, right after the five-day in-person mandate — and the vaccine mandate — took effect.

The IBO says the agencies with the largest holes right now are the Department of Health and Department of Social Services, each with a vacancy rate of 19%, and the Department of Buildings, 24%.

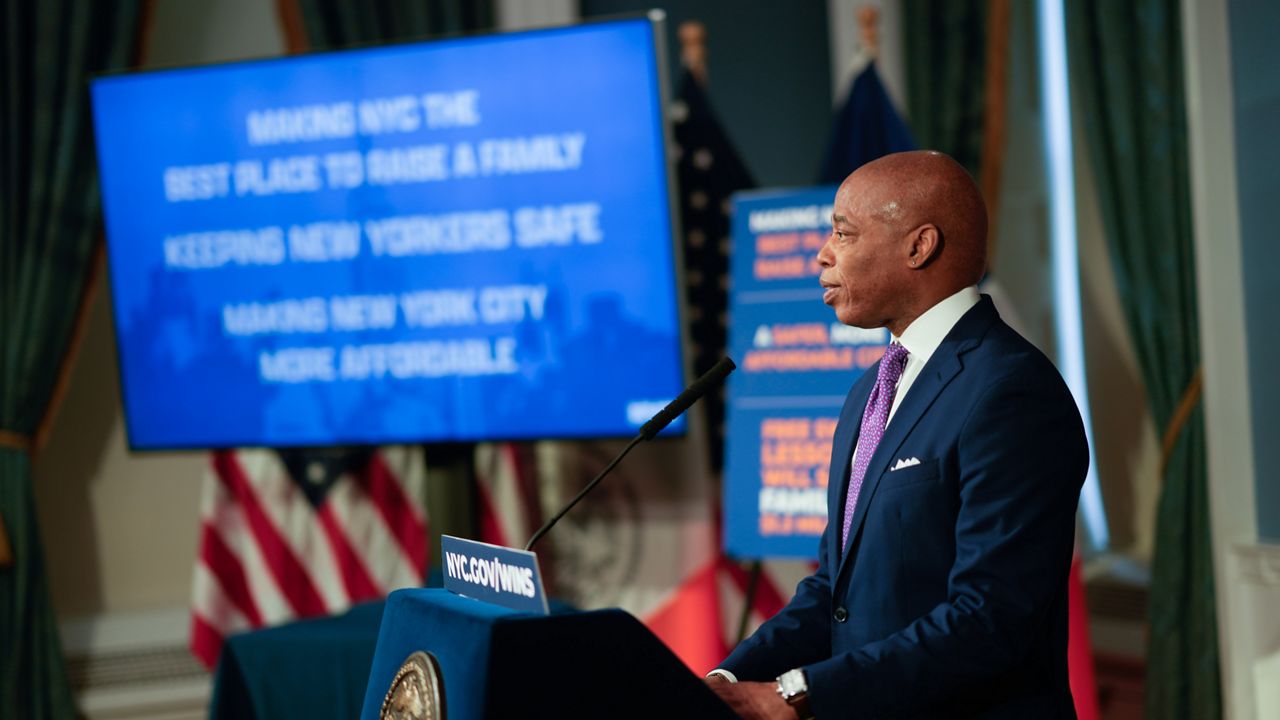

The Mayor’s office points out this is not a NYC-specific issue, rather these trends are being felt in cities across the nation and industries across the board, and sent NY1 the following statement:

“In the early months of his administration, Mayor Adams has built a diverse and highly-talented team that is laser-focused on delivering results and getting stuff done for New Yorkers. And over these first eight months we have done just that despite a labor shortage that has affected almost every sector nationwide, including government.”

“The city has faced no operational impact to services with the vacancies that exist, but we are recruiting aggressively for every vacant position," the statement continued. “Additionally, returning to in-person work has been shown to improve employee productivity, allow for a greater cross-pollination of ideas, and boost mental health — and the city is leading by example, while encouraging private sector employers to bring their workers back to the office as well.”

“Just because the number is going down, that alone isn’t an indicator of a problem,” said George Sweeting, the acting director of the NYC IBO. “Question is, ‘Why is it going down, and what effect does it have on the performance of city agencies?’”

That’s what Sweeting is now working to figure out.

“We don’t know enough about what it actually means on the street in order to know how big of an effect that’s having,” Sweeting said.

Whether people are leaving for the private sector or leaving the workforce altogether, Sweeting says one thing’s for sure.

“The fact of the matter is, in the current labor market, there are many positions that do not require people to be in five days a week,” said Sweeting.

That includes Martin’s new job at a PR firm, doing similar work as he did for the city that he says is just as fulfilling, and way more flexible.

Martin says he chooses to go into the office two or three days a week, and is making nearly double what he was making with the city.

“I thought to myself, it’s kind of doing me a disservice, both from a personal and career standpoint not to explore my options here,” Martin said.

Martin believes COVID provided an opportunity to reimagine how the city works.

“Millennials and Gen Zers, I feel like we’re a very idealistic generation and we want to make change and working in government is the best way to do that,” Martin said. “But sometimes government makes it so hard to do that.”

For Martin, the unwillingness to adapt proved to be a deal breaker.

“When you don’t have that, it’s hard to see how things can change to make things better for all New Yorkers,” said Martin.