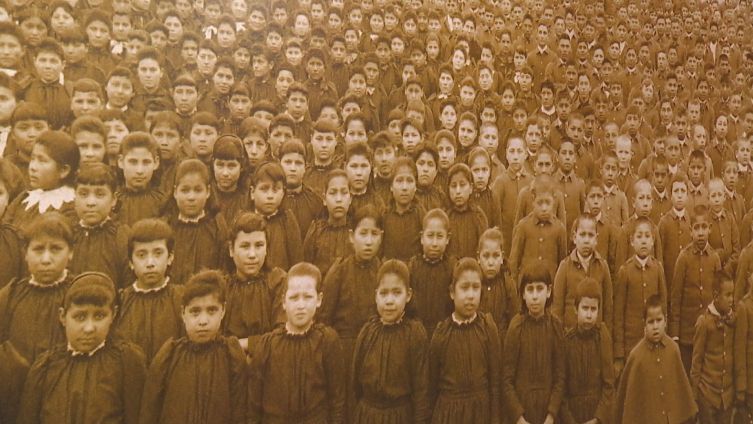

For more than a century, the federal government supported or operated hundreds of Native American boarding schools, fostering an educational system that attempted to assimilate indigenous people.

The school system used militarized and identity-alteration methods, including renaming American Indian children with English names, cutting off Native American students’ hair, and discouraging American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian languages, religions and cultural practices, according to a recent report from the Interior Department released earlier this year.

The schools used corporal punishment to enforce their rules, including placing children in solitary confinement, flogging, withholding food, whipping, slapping and cuffing, the report said. At times, the schools ordered older children to discipline younger ones.

An initial analysis found that 19 boarding schools accounted for the deaths of more than 500 children — a number the Interior Department expects to increase as it continues its probe.

The last of the boarding schools closed more than 50 years ago, but the federal government is just now beginning to own up to the legacy the institutions left behind.

For one group of families, that means receiving the remains of children buried at one school and returning them to their native home.

The headstones in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, give a glimpse into the town’s dark past. Row after row of gravestones, each one marking the death of a child that spent precious little time on Earth. Dates of death that came far too early.

More than 150 children lie in the Carlisle Barracks Post Cemetery; many of them were students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which closed in 1918.

Many of the children died from diseases like tuberculosis. The one thing they had in common is they never returned home.

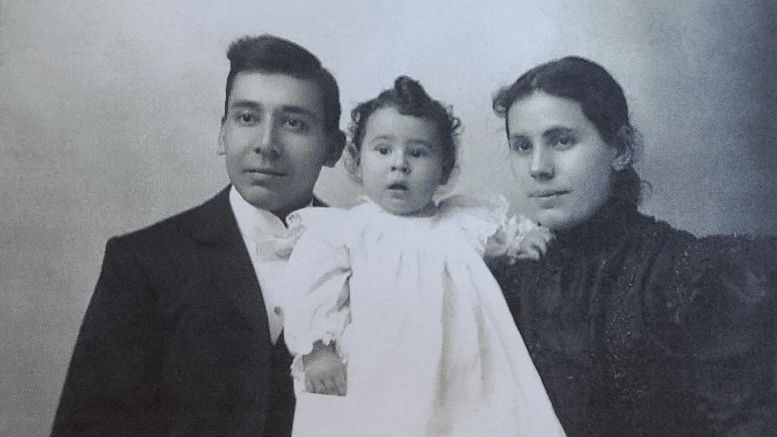

One such child was Paul Wheelock, who died in 1900 at just 10 months old.

“He is so beautiful," Loretta Webster, Paul's cousin, told Spectrum News. "Oh, God, it brings tears to my eyes."

At the time, the school said Paul "took a severe cold which settled in his throat and lungs, from which he slowly pined away.”

Cara Artman, another of Paul's cousins, described him as "a beloved child who was born here, by parents who got a lot out of Carlisle and found the benefits of Carlisle."

Paul, who was too young to be a student, was the son of Dennison Wheelock, a graduate of Carlisle who became the school’s bandleader. Dennison Wheelock was a highly accomplished community leader and lawyer who eventually argued cases on behalf of Indian nations before the Supreme Court and the U.S. Court of Claims.

While Paul Wheelock was believed to have had a positive experience during his short time at Carlisle, other children coming from tribes around the country did not.

When asked how scary it must have been for kids to be placed in Native American boarding schools, Cara Curtis, the Archives and Library Director at the Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, Historical Society, said it was "terrifying" to see children in this situation.

"To be put into kind of identical clothing, having their hair cut, just removing everything, would have been scary," she said.

The goal of Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which served as the model for Native American boarding schools was even scarier. The goal of Carlisle, Richard Pratt, described the mantra of the school as “kill the Indian, save the man," and made a convincing argument for families to send children to the school.

"If you want your children to do better than you did, they need to know English, they need to be able to fight back and to defend their cultures," Curtis told Spectrum News.

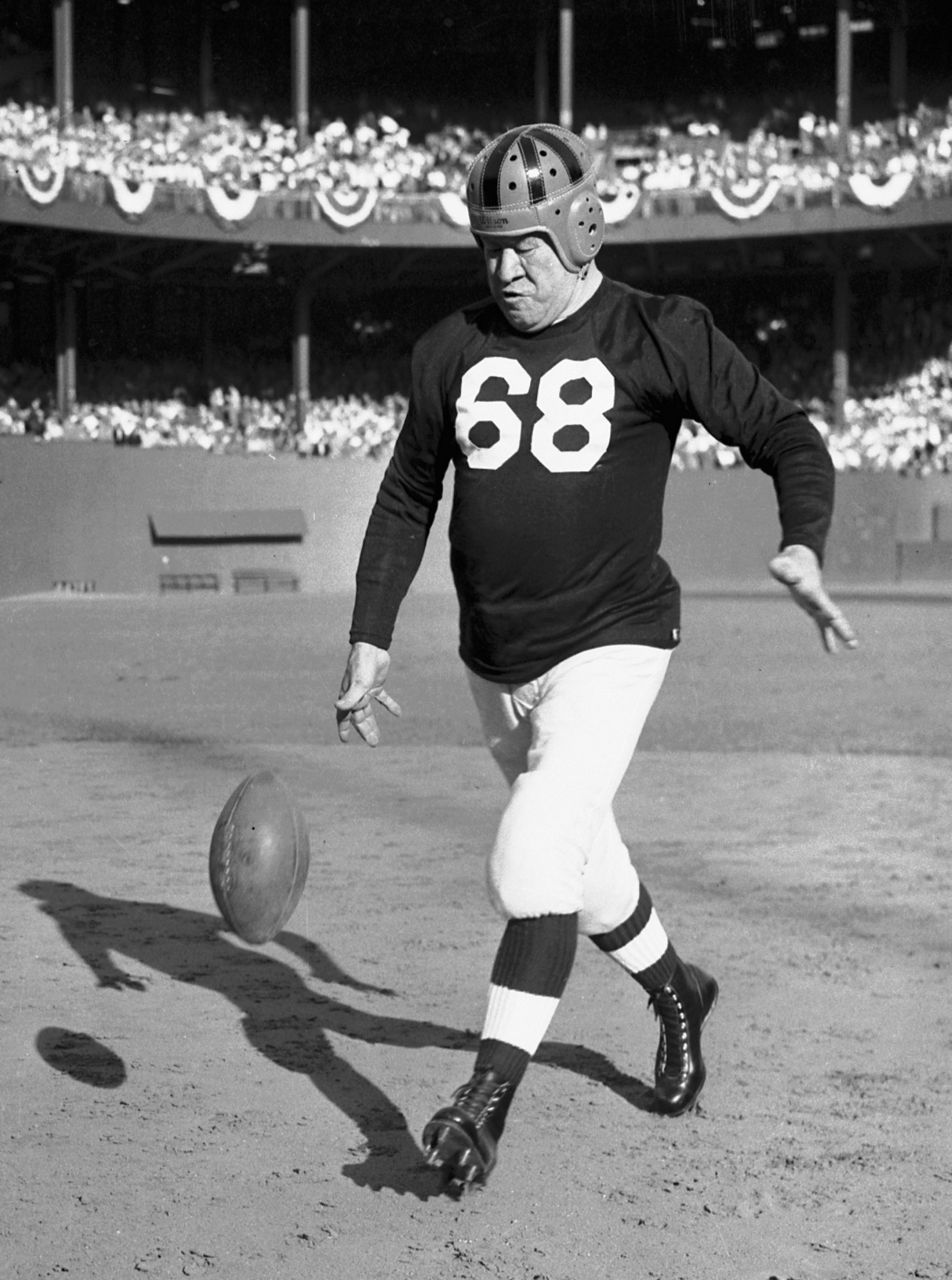

Curtis said the school did see a number of successes, including a nationally recognized athletics program, which included Jim Thorpe, the first Native American to win an Olympic Gold Medal for the United States, among its notable graduates.

“He’s an insanely good athlete," she said. "Modern football was basically created at the Carlisle Indian School."

But while there was triumph, there was also much pain; Curtis said children were forced to do manual labor, were physically abused and were prohibited from speaking their native language.

While some students were sent there by their families, others were forced to attend by the federal government. Some students didn't see their families for years.

When asked how Carlisle should be remembered for, Curtis said it "helped develop a policy for cultural genocide and harm to students."

"We have to come to terms with the history locally, as a nation and world as well," she said, adding: "A reckoning, for sure."

And a reckoning is indeed underway: This is the fifth summer the Office of Army Cemeteries has exhumed the remains of children and returned them to their tribes. Families from around the country have flocked to Pennsylvania to take part in a ceremony before returning with their family members' remains.

More than a century after his death, Paul Wheelock's body is with the Oneida tribe in Wisconsin, buried on land where his family lives – family that did not know he existed until just a few years ago.

Paul's family says that "it's not too late."

"Not for us, not for our family," said Cara Artman. "It's not too late at all. It's never too late to return a child home to their homeland."

Read more: 'I won't let them take my dignity': Survivors of Native American boarding schools speak out