It’s the attempted secession of Staten Island, the sequel.

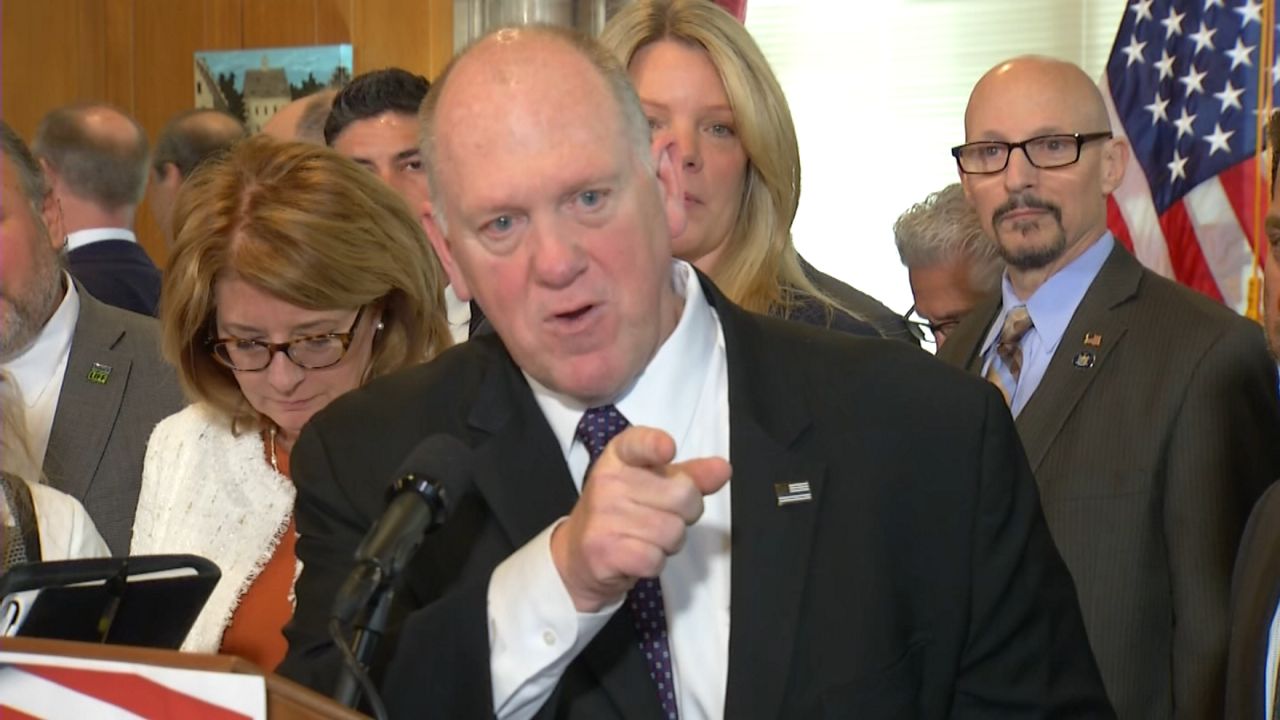

“If we could be our own city, we could control our own destiny in terms of education,” said City Council Minority Leader Joe Borelli.

“We could control our own destiny in terms of law enforcement, we could control our own destiny in terms of how big the government is, how much money we’re going to spend.”

On Thursday, the Staten Island Republican again introduced legislation to create a task force that would study and report on the “feasibility of an independent city of Staten Island.”

But could the so-called “forgotten borough” truly break away this time?

“Secession talk has been on the table since consolidation in 1898,” said Richard Flanagan, a professor of political science at the College of Staten Island. “Probably the biggest obstacle is just the enormous administrative lift.”

Staten Island differs from the rest of the city in that it’s a more politically conservative bedroom community with no subway system.

It came closest to secession in 1993, when a non-binding referendum found two-thirds of borough residents backed the bid, championed by Republican state Senator John Marchi, who had the ear of Democratic Gov. Mario Cuomo.

“That was a particular moment in time when everything came together,” Flanagan said, adding that there hasn’t been a moment like that since.

But the prospect in the 1990s ended without State Legislature approval.

Borelli, with help from fellow Republican Staten Island Council Member David Carr, hopes to recreate the groundswell of support.

“We want to govern it as a suburban community,” Borelli said, “and not necessarily just see it as some appendage of a city, who only wants to dump the bad stuff on us and never seems to want to bring in subway lines or bring in bus rapid transit or finance infrastructure projects.”

With a population of about 493,000, Staten Island would be one of the largest cities in the nation.

The borough has just three City Council representatives in a legislative body of 51, but it also benefits from Manhattan’s tax revenues.

“The price of that freedom would likely be higher taxes,” Flanagan said. “I suspect that’s something that a majority of Staten Islanders would be willing to pay.”

Council Speaker Adrienne Adams of Queens acknowledged the possibility of a Staten Island-less New York this way: “I love Staten Island. I would hate to see them leave us.”

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the year that the five boroughs were consolidated.