This story is the second installment of “The Voting Project” an ongoing series examining the ins and outs of the election process. For more click the link below:

Voting. It’s the cornerstone of our democracy, and in fewer than 90 days, ballots will be counted for a presidential election like no other.

It always promised to be a contentious election – based on who was on the ballot, with recent protests heightening political interest. Now, no matter who Americans want in the Oval Office – how they exercise that choice this year seems to be amplifying everything difficult and controversial about November 3rd.

It’s also throwing into doubt whether the winner will be known on or even near that date.

It all boils down to this question on voters’ minds: How can Americans vote safely during a global pandemic?

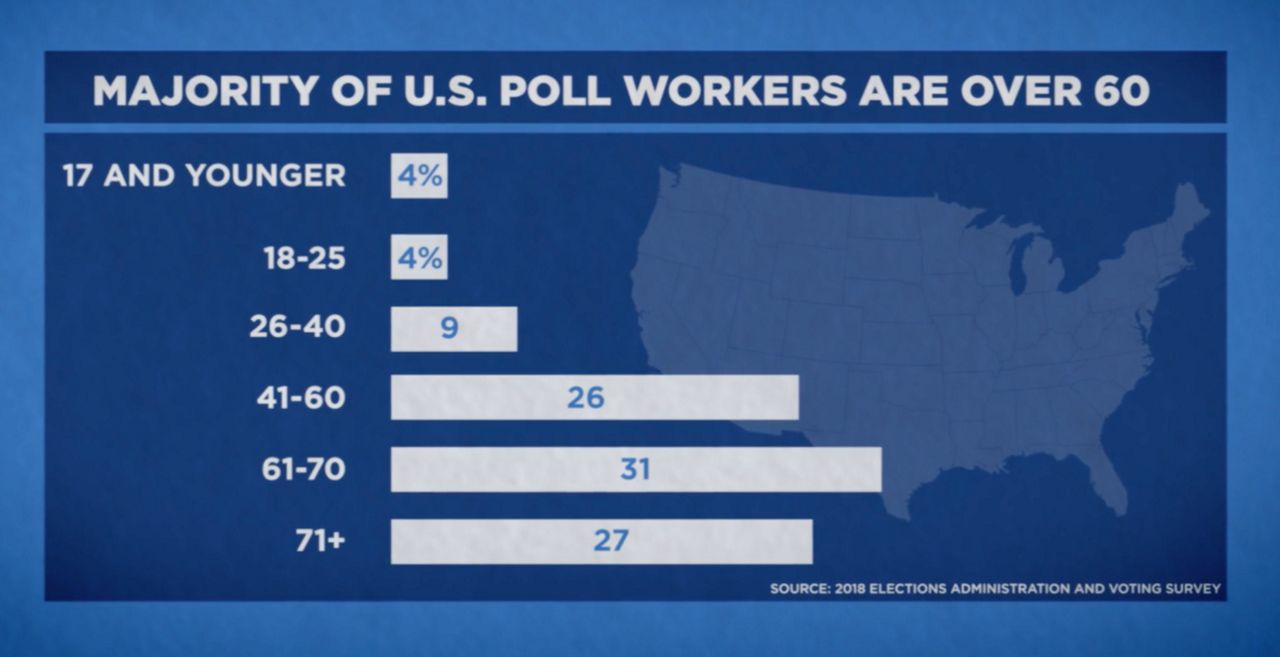

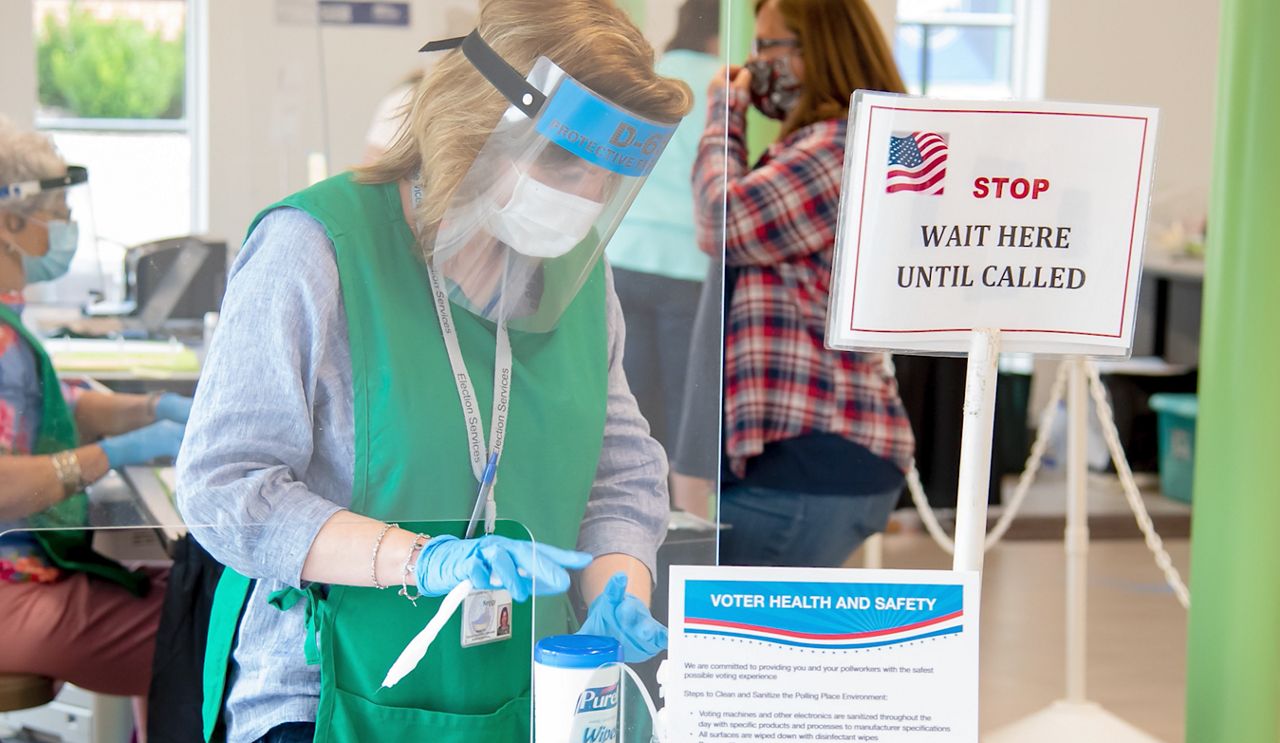

Voting procedures are changing everywhere. Election officials are spacing out polling spaces, buying sanitizer, handing out masks, and racing to find younger poll workers, with more typically older employees balking. A majority of them are over 60 years old.

That all comes not just during an era of a highly contagious virus, but during an era of economic distress, with unemployment decimating local budgets that have to pay for such things.

Still, spacious polling sites and extra hand sanitizer may be the easy lifts for local voting districts. It’s a simple desire from voters that is unleashing the greatest complications: that they never show up at a polling site at all.

“It's obviously safer to vote in the comfort of your own home,” said Lori Edwards, Supervisor of Elections in Polk County, Florida.

Votes through the mail accounted for about a fifth of all votes cast in the 2016 presidential election. Fear of contracting the deadly virus is turbocharging demand. It is highly likely that number will grow, even precipitously.

A recent poll found that more than half of Americans think voting should be done through the postal service. Sixteen states and the District of Columbia have now ramped up access to mail in voting or absentee voting.

Election supervisors and the U.S. postal service are struggling to keep up.

“The big question that we have outstanding is, are election officials going to be able to deliver a supply of ballots and meet the demand for voting that is undoubtedly going to happen come November?” said Michael McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida.

Now, something important and often overlooked: both terms – mail-in voting and absentee voting – are sometimes used interchangeably. Technically – there is a difference. Mail-in ballots are sent to all voters; absentee ballots have to be requested.

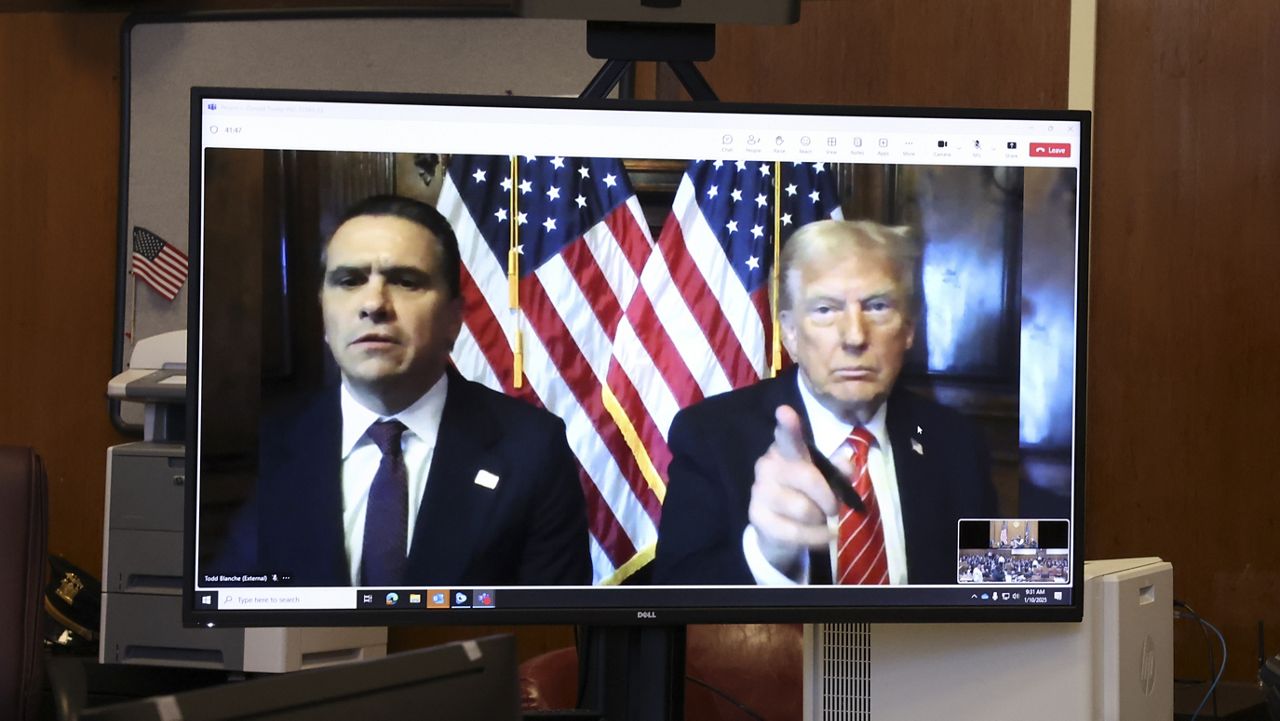

Mail-in ballots are drawing the most concern, and controversy – especially from President Donald Trump.

“You’ll have tremendous fraud if you do these mail-in ballots. Now, absentee ballots are okay,” he said recently.

Experts say absentee ballots and mail-in voting essentially serve the same function, but regardless, they say the President is greatly overstating the risk of fraud. According to multiple studies, instances of voting fraud are extremely rare -- so rare, in fact, to be dubbed “infinitesimal” in one report. And voting outside the polling place, absentee and mail-in, is championed by members of both parties.

“There's always going to be someone who tries to game the system,” McDonald said. “But from what we know, those are isolated incidents.”

Still, there are problems with mailed ballots. Voter errors lead to them being rejected. And in certain primary elections, like in Ohio and Wisconsin, crushing numbers of absentee ballot requests led to some votes not being counted. A recent study also found that in 2016, about 1.4 million votes — 4.0% of mail ballots cast and 1.0% of all ballots — were “lost votes” — “when a voter does all that is asked of her, and yet her vote is uncounted in the final tally.”

“Despite the clear public health imperative that mail balloting be increased in the 2020 primary season and general election, the expansion of mail balloting comes with risks,” wrote the author, Charles Stewart III of MIT, according to The New York Times.

“To be sure, these risks are small, and should not be sensationalized,” he noted.

Significant budget issues in the U.S. Postal Service also raise concerns. The Postal Service was struggling to deliver election mail in a timely manner even before the pandemic.

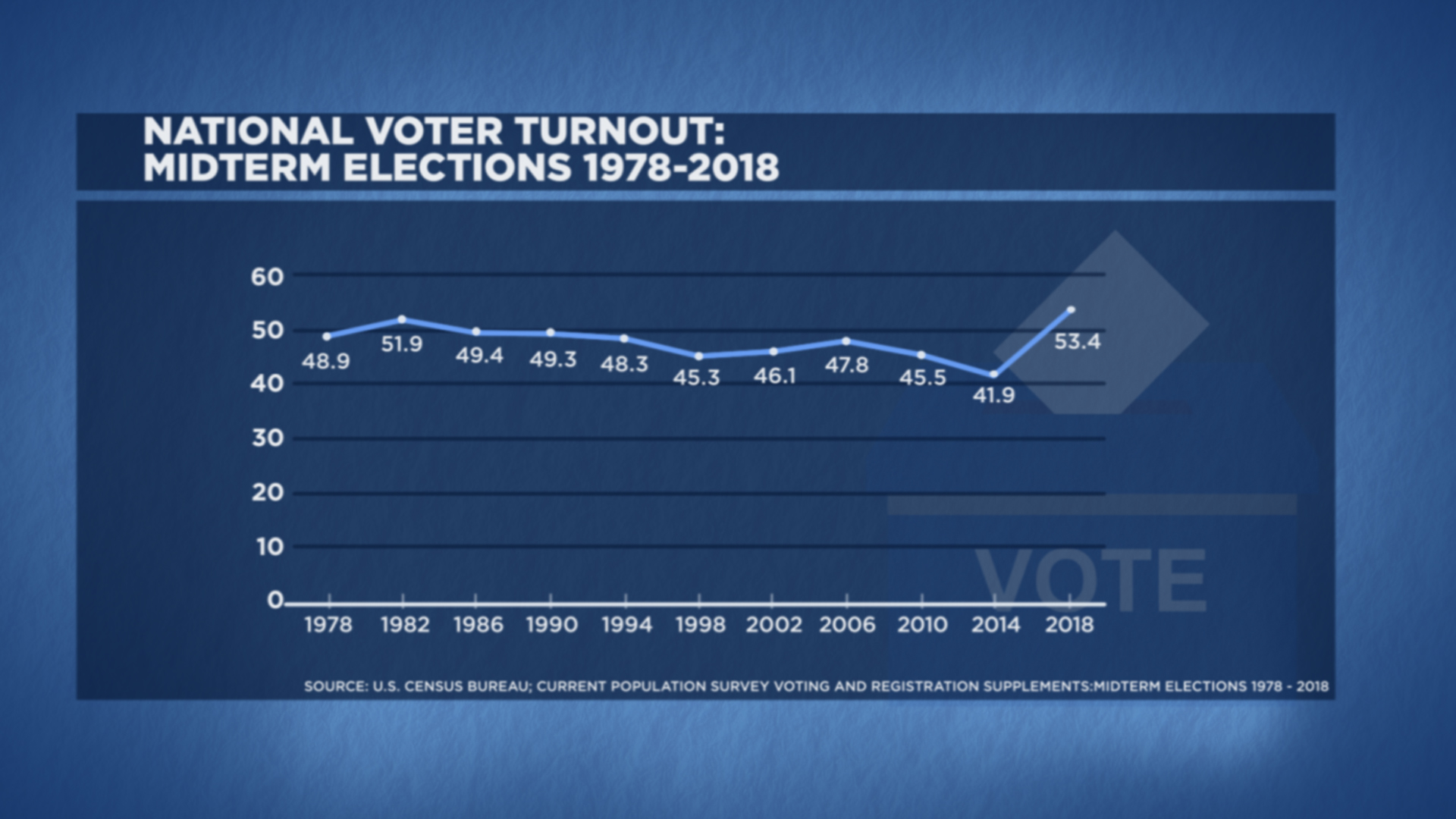

During the 2018 election, which had the highest midterm turnout in more than a century, the seven lowest-performing mail processing centers – in swing states like Ohio, Florida, and Wisconsin – only delivered an average of 84.2% of election mail on time, per an internal report.

Results of a primary in New York on June 23 are still being challenged - due to concerns over mailed ballots. That has many asking If that’s the case locally, what will happen nationally?

“You know, you could have a case where this election won’t be decided on the evening of November 3rd,” President Trump said in a recent interview with Axios. “This election could be decided two months later.”

It’s unclear whether it will be many months; yet with a large number of absentee or mailed ballots uncounted on Election Day, it seems quite possible that the results will not be known the night of November 3, as has generally been the modern custom.

But November 3 will still be Election Day, as it has since 1845. Late last month, President Trump floated delaying the contest. That would take an act of Congress, which has shown no indication it will follow that idea.

There are bright spots – fears of a botched primary in Kentucky failed to materialize after a bipartisan agreement. And election workers everywhere say they’ve learned from their experiences in the 2020 primaries.

“We had to scramble, scramble, scramble,” said Edwards, the election supervisor from Florida.

“Now, at least going into August and November, we know what we're dealing with.”

“The phrase that we've been using is that those are our heroes of democracy,” added Karen Brinson Bell, Executive Director of the North Carolina Board of Elections, said of election workers.

“And while we often hear right now that heroes don't always wear capes, that's going to be very true. Our heroes will be wearing precinct official gear and face masks come November.”