On Jan. 21, 2025, regardless of who wins the 2024 presidential election, one thing will be certain: For just the second time in more than 50 years, Joe Biden will no longer be an elected official.

Biden’s extraordinary decision on Sunday not to seek reelection — a choice he expanded upon in an Oval Office address to the nation on Wednesday — is the beginning of the end of a half-century career in politics marked by reaching extraordinary highs and experiencing almost unfathomable personal lows.

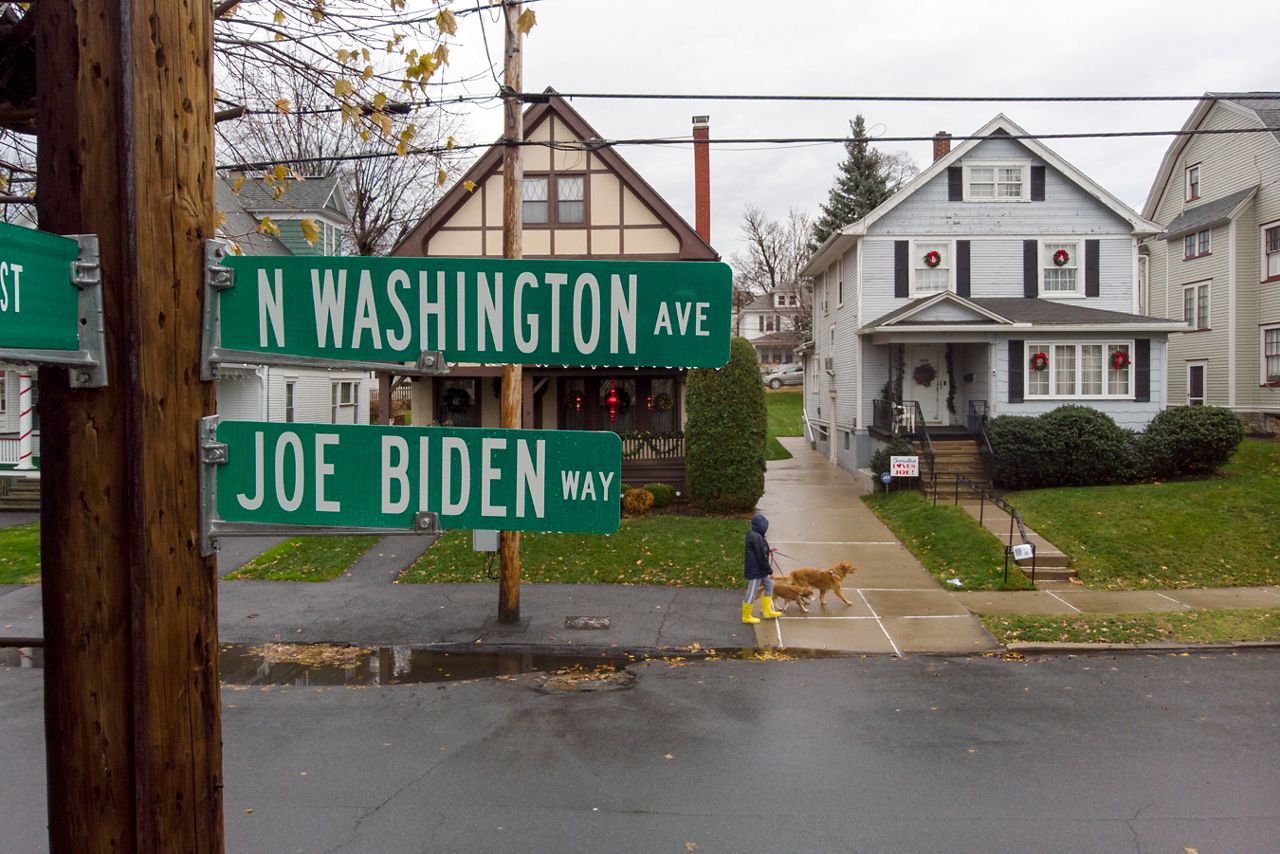

“It’s been the privilege of my life to serve this nation for over 50 years," Biden said. "Nowhere else on Earth could a kid with a stutter, from modest beginnings of Scranton, Pennsylvania, and Claymont, Delaware, one day sit behind the Resolute Desk."

"But here I am," he added.

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr., was born on November 20, 1942 to Catherine Eugenia "Jean" Biden (née Finnegan) and Joseph Robinette Biden Sr., in Scranton, Pennsylvania. His family started off wealthy, at one point owning a house in an affluent part of Long Island, New York, but Biden’s father suffered some financial setbacks and the family was forced to move back in with his maternal grandparents.

During Scranton’s economic downturn in the 1950s, Biden’s father struggled to find steady work, moving the family to Delaware, where he eventually found success as a used car salesman.

These formative experience helped shape Biden’s worldview and politics, often talking about his parents and grandparents in his stump speeches throughout his career.

Invoking his father to talk about the importance of growing out the middle class, Biden would say that “a job is about a lot more than a paycheck, it’s about your dignity. It’s about your dignity. It’s about being able to look your kid in the eye and say everything is going to be OK, and mean it.”

From his mother, Biden learned about toughness and the importance of family. The president told iconic radio host Howard Stern in an interview earlier this year a story of a nun who taught at a school he attended who mocked his stutter, a speech impediment he struggled with all his life.

In the interview, Biden recalled his mother saying: “If you ever speak to my son like that, I’m going to come back and rip that damn bonnet off your head. Do you understand me?”

“It taught me a lot,” Biden later said. “No one in my family, no matter what a jerk somebody was, you could never say something about them that was true, that they couldn’t control.”

After attending Archmere Academy in Claymont, Delaware, where he was a standout football player and also played outfielder on the school’s baseball team, Biden attended the University of Delaware. And on one fateful spring break in the Bahamas, he met the first love of his life, Neilia Hunter.

Biden told Stern that he and two friends snuck into a hotel pool in the Bahamas, where he first spotted Neilia — and he and another friend flipped a coin for who would go talk to her. He won.

“To make a long story short, I’m sitting talking, I said, ‘Hi, my name’s Joe Biden, I’m from Delaware.’ She said, ‘My name is Neilia Hunter, I’m from Syracuse,’” he recalled in the interview.

Later, the two went to dinner, and Biden was short $20 on the bill.

“At this nice restaurant, I ordered a hamburger,” Biden told Stern. “And her family had money, but she ordered the same thing. She was very gracious. And bill comes, and I was 20 bucks short, and I could feel a tap under the table on my knee. And I put my hand down and she put 40 bucks in my hand.”

When asked if he fell in love with her right at that moment, Biden replied: “I did.”

He began commuting on weekends to visit her in Syracuse — her family came from a wealthy background in nearby Skaneateles, an affluent lakeside community — and eventually he joined her at Syracuse University, attending the storied institution’s law school.

The two were married while Biden was in law school in 1966 and he graduated from Syracuse in 1968 — though he failed one course after inadvertently plagiarizing a paper; he later retook it and the failure was stricken from his record — and he began clerking at a Wilmington law firm helmed by a prominent Republican figure in local politics.

“When I got a job, I got a job with one of the best, most prestigious plaintiff firms in the state,” Biden told Stern. “But [civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.] was killed that summer, that year, and we were the only city in America occupied by the National Guard for 10 months … so I quit and became a public defender."

He also got involved with the New Democratic Coalition, a group attempting to reform the Democratic Party, before running for a seat on the New Castle County Council in 1970, which he won, beginning his entry into politics.

Two years later, Biden mounted a challenge to incumbent Republican Sen. J. Caleb Boggs in his first bid for U.S. Senate. With limited campaign funds and a staff comprised of members of his family — including his father going door-to-door — Biden’s bid to oust Boggs was seen as a long shot.

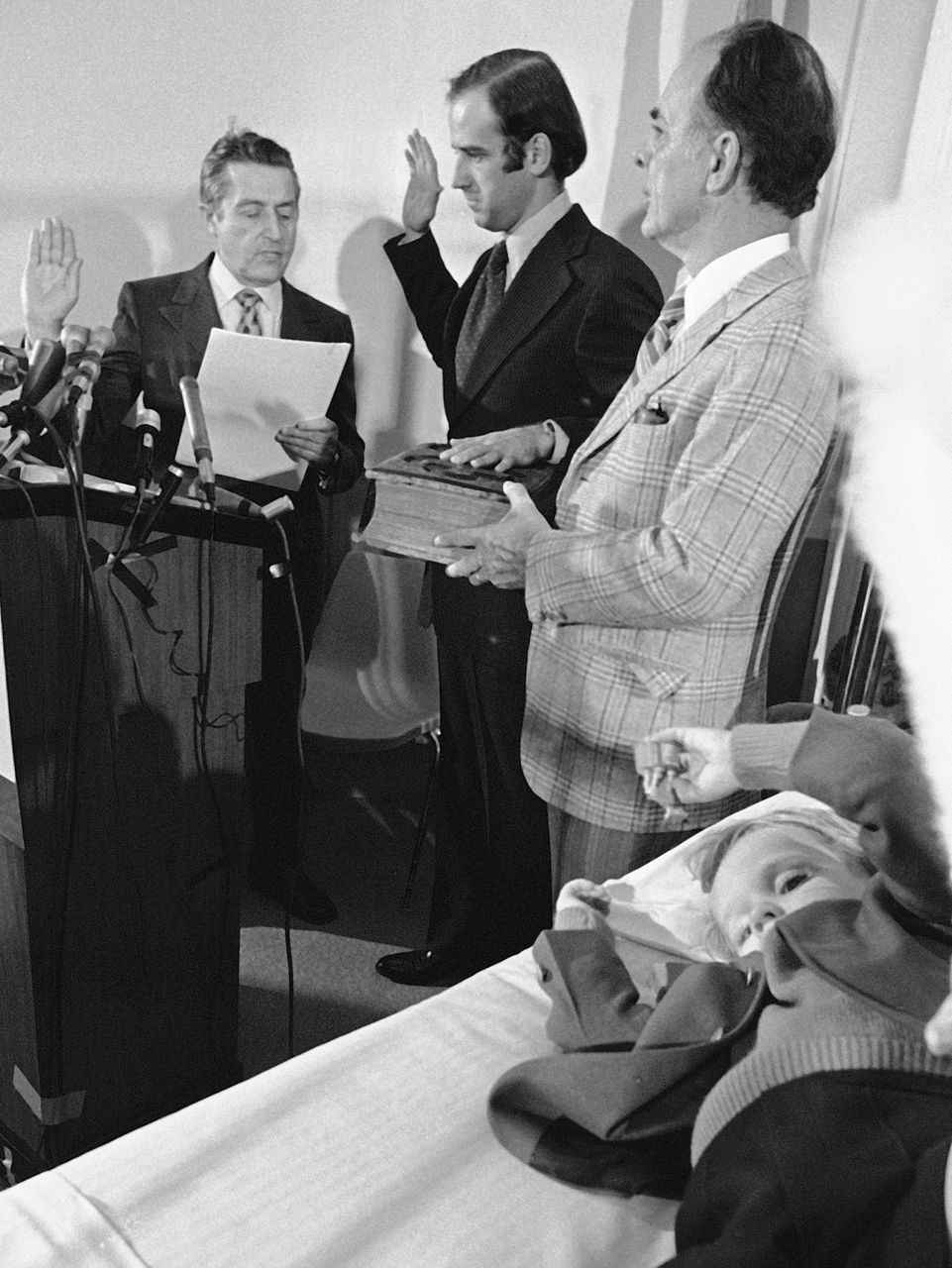

Despite headwinds, including Democrat George McGovern’s loss to President Richard Nixon in the state by more than 20 points, Biden eked out a win, becoming the youngest person at 29 years of age to be elected to the U.S. Senate in nearly 40 years.

He would go on to be reelected seven times to represent Delaware in the U.S. Senate before he became vice president in 2009.

But before he could take office for the first time, an unimaginable tragedy struck.

A few weeks after Biden was elected, his wife Neilia and their children were involved in a car accident while Christmas shopping in December of 1972. Neilia and their infant daughter Naomi were killed, and their sons, Beau (then 3) and Hunter (then 2), were seriously injured.

“The underpinnings of my life had been kicked out from under me,” he wrote in his book, “Promises to Keep,” published in 2007. “No words, no prayer, no sermon gave me ease. I felt God had played a horrible trick on me, and I was angry. I found no comfort in the Church.”

Biden considered resigning from the Senate, but he was convinced to stay.

"I didn't want to stay in the U.S. Senate, and I let everybody know," Biden told Howard Stern earlier this year. "We had a Democratic governor, and he'd appoint a successor, another Democrat.”

He met resistance from some of the powerhouses of the U.S. Senate at the time — namely then-Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, Massachusetts Sen. Ted Kennedy and a handful of others — who convinced him to stay.

"Sen. Mansfield, 'Iron Mike' from Montana, a man with more integrity in his little finger that most people have in their whole body, and Teddy Kennedy and [South Carolina Sen.] Fritz Hollings ... and a few others, they all came to me and said 'look, just stay six months, help us organize,'" he recalled. "Like a damn fool, I said, I said 'OK, but I'm not going to stay.' And I started commuting back and forth to the train and two or 300 miles round trip a day."

Biden’s travel on commuter rails earned him the nickname “Amtrak Joe,” which stuck with him throughout his career in Washington.

He leaned on his parents and his siblings during that time, expressing that he could not afford child care — he’d drop his children off at his mom’s before taking the train to Washington, his brother James moved into his garage, his sister Valerie helped look after the boys.

Biden, in his interview with Stern, expressed that he had thoughts of suicide after suffering that great loss.

"I don't drink," Biden replied. "That's not a virtue, I never drank. And I used to sit there and think to myself, 'I'm just gonna pick out a bottle of scotch ... and I was going to just drink it and get drunk, and I could never bring myself to do it."

"And I actually thought about — you know, glioblastoma — you don't have to be crazy to commit suicide," he continued. "If you've been at the top of the mountain, you think it's never gonna be there. And there was a brief moment, I thought maybe I just go to the Delaware Memorial Bridge and jump. But I had two kids. Don't get me wrong. I wasn't like, 'I've got to commit — It was like, you've been to the top of the mountain, and it's never gonna happen again. You're never gonna be OK. But I had my boys."

When asked if he considered therapy, Biden said he didn't, emphasizing the support of his family — but encouraged others to seek mental help.

"I strongly, strongly, strongly encourage people to go to therapy," Biden said. "I strongly urge people to deal with mental illness. It's just like you breaking a bone in your body, but I guess because I had such an internal support ... I never considered it, but I wish I had. I remember when the boys were hospitalized, Hunter had a fractured skull from the accident and Beau broke literally every bone in his body, he was in a body cast both arms, both legs for a long time."

Biden recalled that Ted Kennedy sent a child therapist from University of Massachusetts to help his children recover from the accident, which he said was "wonderful."

"I encourage people to get therapy, I hope they don't read from this and they shouldn't get a therapist," Biden said. "I think it's really important. Mental illnesses should not be viewed as anything different than a physical illness, and it should be just treated. And there's real serious people and experts who can help."

Biden served in the U.S. Senate under seven presidents — Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. He started his career in the upper chamber of Congress alongside the likes of Bob Dole, George McGovern, Walter Mondale, Adlai Stevenson and Strom Thurmond, and ended it with Hillary Clinton, Harry Reid, Chuck Schumer, Mitch McConnell and a young upstart from Illinois by the name of Barack Obama. (Remember that last name, it may come up again.)

Biden took office at 30, the sixth-youngest U.S. senator in the country’s history. He described having a great difficulty focusing during his early Senate career.

“I had a great deal of trouble focusing. I had three children and the two that survived … were badly injured,” Biden said in an interview with NPR in 2007. “I did my job, I didn't miss the votes, I showed up. But I just could hardly wait to get home.”

But he worked on matters of campaign finance reform, of consumer protection and issues related to the environment during his first term.

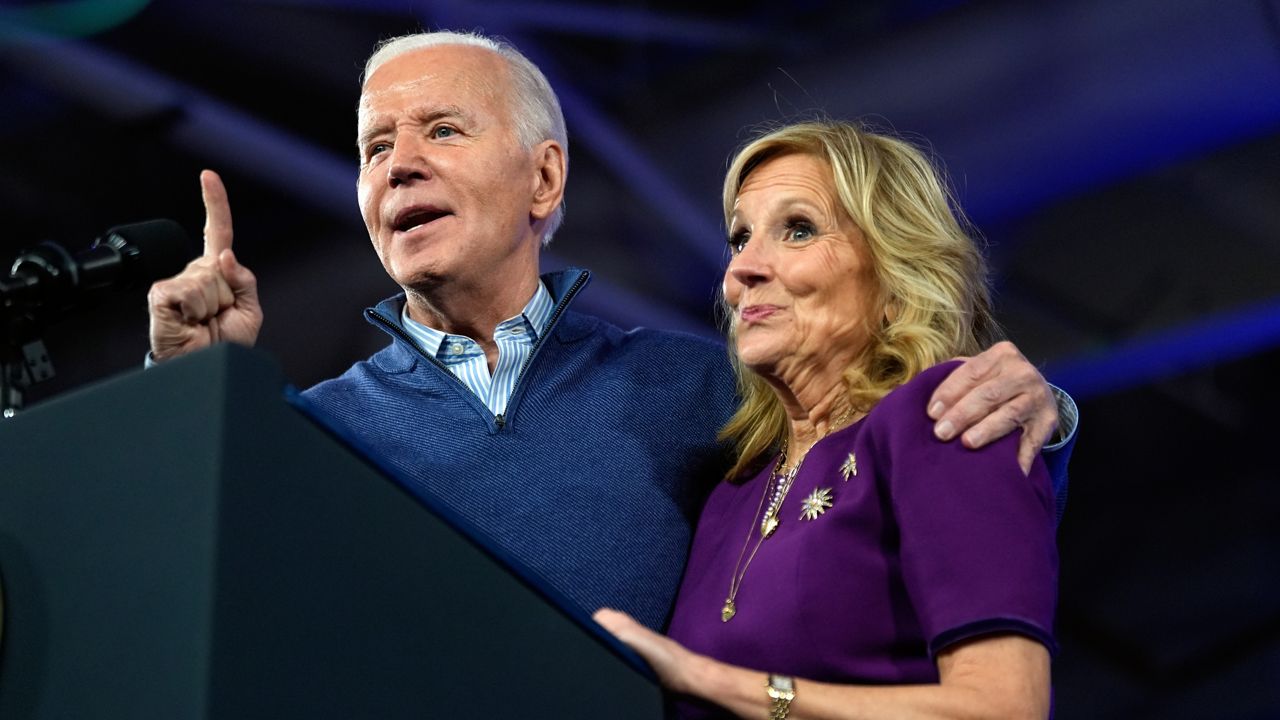

And during his first term in office, he met the second love of his life: Jill Tracy Jacobs, the future first lady of the United States.

The two were set up on a blind date by Biden’s brother, Frank, who met her in college. Biden told Howard Stern it was love at first sight.

“For me it really was,” he said. “I mean, I just liked her. We have the same family values.”

After proposing multiple times — she was hesitant about being in the public eye, wary about her own career as a teacher and sensitive to the prospect of raising Biden’s two sons — she said yes, and the two were married in June 1977. Together they have one daughter, Ashley, and Biden’s two sons called her mom.

Biden told Howard Stern that Beau and Hunter, his sons, gave him “permission” to marry Jill.

“They came in one morning, I’m brushing my teeth, and Beau looked at Hunter and he said, ‘You tell him,’ Hunter said, ‘No, you tell him,’” Biden recalled. “I finally said, ‘Boys, what are you going to tell me?’ And Beau said, ‘you know, dad, Hunt and I think we should marry Jill.”

And when they got married at the U.N. Chapel in New York, when the priest asked “who takes this woman,” both boys stood by his side, he recalled.

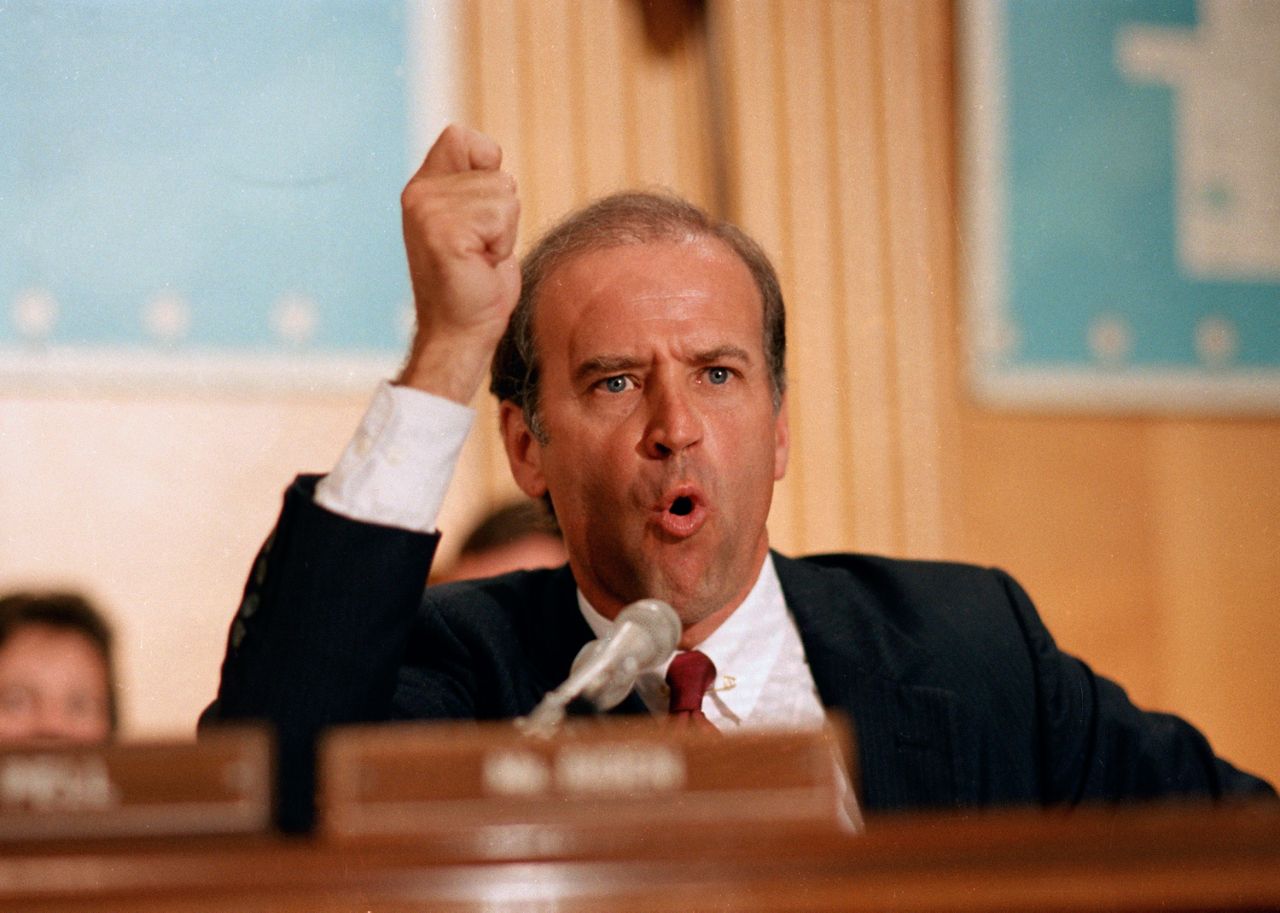

Biden’s lengthy career in the Senate includes his helping to pass the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which included the Violence Against Women Act and a ban on assault weapons, both of which he champions to this day as president, but called the bill “a big mistake” in 2019 for the bill’s toughening of sentences for crack cocaine possession, saying it “trapped an entire generation.”

He was also a key member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, serving as both its chairman and ranking member over the years, experience which gave him keen insight as he nominated his own justice to the high court in 2022. He oversaw the failed nomination of Reagan’s pick Robert Bork and the contentious hearings over Clarence Thomas, which involved Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment. (Biden later apologized for his treatment of Hill, which she said left her unsatisfied, per The New York Times.)

Biden also served in the top roles on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. On matters of foreign affairs, Biden voted against authorization of the 1991 Gulf War, but was supportive of intervention in the Balkans. He recounted that he once called Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević “a damn war criminal” who “should be tried as one.”

Biden, who proudly touts his Irish roots, pushed the Clinton administration to help broker the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended the sectarian violence in Northern Ireland also known as “The Troubles.” Along with longtime friend Sen. John McCain, Biden sponsored a bill pushing President Clinton to “use all necessary force” to confront Serbian forces in Yugoslavia. And while he supported both the war in Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, he eventually became a staunch critic of the latter — and, much later, oversaw the withdrawal of U.S. forces from the former as president.

And twice during his U.S. Senate career, he briefly flirted with the idea of becoming president of the United States.

Biden first tried for the White House in 1987 for the 1988 presidential election, touting strong fundraising, his age — he would have been the youngest president since John F. Kennedy — and his popularity as a U.S. Senator.

But his first campaign was short-lived, dogged by a plagiarism scandal — he was accused of lifting a speech from British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock, then the Syracuse plagiarism story was discovered — and he withdrew before the primaries.

Biden’s second try came in 2007, declaring for the 2008 election, but he failed to gain much traction against the two highly popular candidates in the Democratic race: Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama.

He was, however, praised for his record, his grasp of issues, particularly on the foreign policy side, and a one-liner directed at one-time Republican candidate Rudy Giuliani: “There's only three things he mentions in a sentence: a noun, and a verb and 9/11.”

After Biden left the race, he and Obama developed a strong relationship, with the two discussing a place for him in his administration.

They eventually found it: Obama named Biden to be his running mate in August 2008.

Biden told Howard Stern he initially didn’t want to be vice president, believing he could be much more helpful to Obama’s agenda in the U.S. Senate, but Obama persisted, urging him to mull it over with family.

Biden called a family meeting, and Jill Biden said he should take it, adding, per his recollection: “‘Otherwise, you’ll be asked to be Secretary of State and you’ll be away all the time.’” (The role eventually went to Hillary Clinton.)

And Biden’s mother, who was still alive at the time, also tried to set him straight on the matter, saying: “‘When I called you and asked you about Barack when he defeated you back in the spring, you said he was bright, he was honest. He was really a capable guy.’”

“I said, Yeah, mom, what’s your point?’” Biden recalled to Stern. And she replied, per Biden: “‘Joey, the first Black man in history has a chance to be president, and you told him no?’"

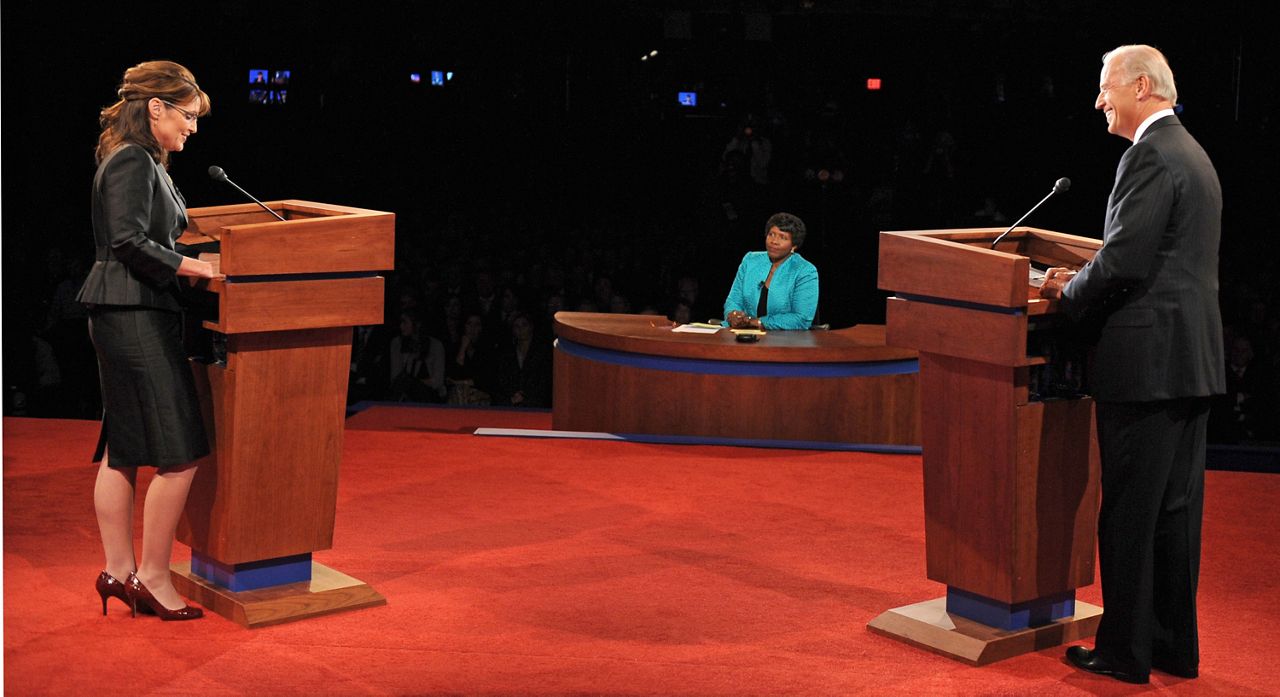

Biden loaned Obama, then a relatively new figure in Washington, crucial experience in foreign policy and national security, and despite being overshadowed by McCain’s choice of Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, he campaigned in swing states, sought to win over blue-collar voters and those who preferred Clinton in the primary.

The two would go on to win a landslide victory over McCain and Palin. At the same time, he was reelected to the U.S. Senate for a seventh term, calling his service to the people of Delaware “the greatest honor bestowed upon me.”

Biden, as vice president, oversaw the disbursement of infrastructure spending from the 2009 Obama stimulus package. He made numerous visits to Iraq, becoming the administration’s point person on the war until the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2011. When Democrats lost a chunk of their majority in the 2010 midterms, his relationships with Republican senators proved useful in a number of negotiations over legislation, including the New START nuclear treaty and the 2010 Tax Relief Act.

He was also no stranger to gaffes and hot mic moments, including an infamous 2010 moment when Obama was signing into law the Affordable Care Act — Biden called it “a big f****** deal.”

With Obama’s second term coming to an end, Biden was reportedly mulling mounting a third White House bid in 2016 — but he decided against it when tragedy struck his family once again.

On May 30, 2015, Joseph Robinette “Beau” Biden III, Biden’s eldest son, died after a battle with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer at the age of 46.

Beau Biden followed his father into public service. After attending the University of Pennsylvania and graduating from his dad’s law school alma mater, Syracuse University, he clerked for a federal judge and worked in the U.S. Attorney's Office as a prosecutor. He also served in the Delaware Army National Guard, joining in 2003 as a member of the Judge Advocate General Corps, serving as an interim legal advisor for the Justice Department in post-war Kosovo and later deployed to Iraq, rising to the rank of Major.

In 2006, he was elected as the Attorney General of Delaware, serving two terms. Considered to be a rising star in politics, Beau Biden introduced his father at the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver. In his speech, he talked about losing his mother and the toll it took on his family, and asked Americans to “be there for my dad like he was for me.”

Beau had intended to run for governor of Delaware in 2016 before his death. (Biden has said in interviews that Beau "should be standing here instead of me.")

Biden took Beau’s death particularly hard, citing it as one of the reasons why he decided not to run for president in 2016, despite the urging of family members, friends and allies.

“Nobody has a right, in my view, to seek that office unless they're willing to give it 110% of who they are,” Biden told late night host Stephen Colbert in an interview in 2015. “I'm optimistic, I'm positive about where we're going, but I find myself, you understand it, sometimes it just overwhelms you.”

In October 2015, he made it official, saying that as he and his family have “worked through the grieving process, I've said all along what I've said time and again to others: that it may very well be that that process, by the time we get through it, closes the window on mounting a realistic campaign for president.”

“I've concluded it has closed,” he said, later adding: “I intend to speak out clearly and forcefully, to influence as much as I can where we stand as a party and where we need to go as a nation.”

“I believe that President Obama has led this nation from crisis to recovery, and we're now on the cusp of resurgence,” he added. “I’m proud to have played a part in that. This party, our nation, will be making a tragic mistake if we walk away or attempt to undo the Obama legacy. The American people have worked too hard, and we have have come too far for that.”

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton would go on to win the Democratic nomination before losing to Donald Trump in November 2016.

After leaving public life for the first time since 1973, Biden joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania as an honorary professor, establishing the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement, published a book, “Promise Me, Dad,” reflecting on losing Beau, and became an outspoken critic of Trump’s policies before formally challenging him in the 2020 election.

Third time’s the charm

Joe Biden kicked off his presidential campaign in 2019, becoming part of a crowded field of Democrats that included established figures like Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who challenged Hillary Clinton for the 2016 nomination, and newcomers like South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg.

Despite polling showing him as competitive with Trump, Biden performed poorly in the early Democratic primary contests of 2020 — he finished in fourth in the Iowa caucuses, a distant fifth in New Hampshire and second in Nevada. With his campaign reeling, he headed into South Carolina to mount a last-ditch effort to salvage his White House bid.

It paid off. After receiving the key endorsement of South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn, an influential figure in Democratic politics, Biden trounced the competition in the state en route to big wins in the Super Tuesday. As his competitors left the race, they coalesced around his candidacy, leading him to victory in April 2020.

In August, he selected California Sen. Kamala Harris, a former primary challenger, to be his running mate, making her the first Black and South Asian vice presidential nominee in U.S. history. After a contentious and fraught campaign amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Biden defeated Trump, thwarting his bid for a second term.

But Trump didn’t go quietly into a presidential transition, instead making numerous false claims of fraud in the election which culminated in a mob of his supporters attacking the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, to disrupt the certification of Biden’s victory.

The insurrection at the Capitol — not unlike the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville that Biden cited as one of the reasons why he wanted to run in 2020 — became a central focus of his presidency, with defending democracy being a recurring theme over the next few years of his term. Trump would end up being impeached for the attack one week later. (He was acquitted by the U.S. Senate.)

On Jan. 20, 2021, Biden took the Oath of Office, and was sworn in as the 46th president of the United States. At 78, he was the oldest person to assume the presidency. His first acts as president included executive orders rejoin the Paris Climate Agreement, reverse Trump’s decision to withdraw from the World Health Organization and enact face mask requirements on federal property to combat the pandemic.

Biden’s administration was marked by a number of legislative successes, enjoying Democratic control of both the House and Senate, including passing the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, a $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill, and the CHIPS and Science Act, which aims to boost domestic semiconductor production.

But he also faced challenges in the form of razor-thin congressional majorities, particularly in the Senate, where any one lawmaker could object to his proposals. His sweeping Build Back Better Act, a $3.5 trillion social spending and climate change measure, was pared back significantly after objections from West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin and eventually passed as a much slimmer deficit reduction, tax reform and climate bill known as the Inflation Reduction Act.

He appointed more than 200 federal judges to the bench, seeking to reverse Trump’s shaping of the judiciary, including Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black woman to serve on the Supreme Court.

On the topic of inflation, rising costs plagued perceptions of Biden’s handling of the economy, leading to sour poll numbers despite record low unemployment and signs that the U.S. is ahead of the rest of the world in terms of economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Biden administration was also roundly criticized for its handling of the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the country’s longest war, which led to the swift collapse of the Afghan government and rise of the Taliban.

On the international front, Biden also marshaled a global response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, particularly in bolstering support for NATO. Under Biden’s presidency, the alliance added two new members, Finland and Sweden, spurred in large part by Russia’s invasion.

He also worked to broker numerous cease-fire agreements between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, despite some souring sentiment at home among his own supporters for backing Israel.

Throughout his presidency, he was dogged with questions about his age and fitness for office, particularly in recent weeks following a debate with Trump that sparked calls from within his own party to step aside for a younger candidate.

Speculation about whether or not Biden would step aside came to an end on Sunday when he bowed out of the race, endorsing Vice President Harris to take his place — and bringing a half-century in politics almost to a close.

’What lies ahead’

In his address to the nation from the Oval Office, just the fourth of his term in the White House, Biden explained his decision about stepping aside. Biden, the second Catholic president to occupy the White House, vowed to continue working for the American people while expressing that the best way forward was to -- perhaps paraphrasing the first Catholic president, John F. Kennedy -- pass the torch to a new generation.

"I revere this office, but I love the country more," Biden said, adding: "The defense of democracy is more important than any title."

"Nothing can come in the way of saving our democracy. That includes personal ambition. So I have decided the best way forward is to pass the torch to a new generation, he continued. "That is the best way to unite our nation."

In recent days, Biden’s Democratic allies have extolled his virtues, with many saying that his decision to step down cementing his place in the history books.

“In one term, he has already surpassed the legacy of most presidents who have served two terms in office,” Harris said Monday.

“By willingly passing the torch, Joe Biden is precisely the kind of leader George Washington would have hoped for,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said on Tuesday. “In his farewell address, our first president affirmed that elected office belongs to no man or woman alone, but to the people above all. Two hundred thirty years later, President Biden honors George Washington’s example in a way few presidents ever have.”

The days, weeks and months ahead will be largely unprecedented — no surprise, given how much that word is bandied around in current events — but what’s certain is that Biden has pledged to be “fully engaged” in Harris’ campaign to deny Trump a second term in the White House.

“The name has changed on the top of the ticket, but the mission hasn't changed at all," Biden said at an event on Monday launching her campaign. "And by the way, I'm not going anywhere, I'm gonna be out there in the campaign with her, with Kamala, I'm going to be working like hell, both as a sitting president getting legislation passed as well as in the campaign.”

While Biden’s legacy will no doubt be debated in the years to come, his half-century in American politics — from the highest highs to the lowest lows — can probably be summed up by one of his oft-invoked favorite lines from his favorite Irish poets, Seamus Heaney.

“History says, don’t hope / On this side of the grave. / But then, once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up, / And hope and history rhyme.”

And as Biden so often adds after reciting that line: “This is our moment to make hope and history rhyme.”