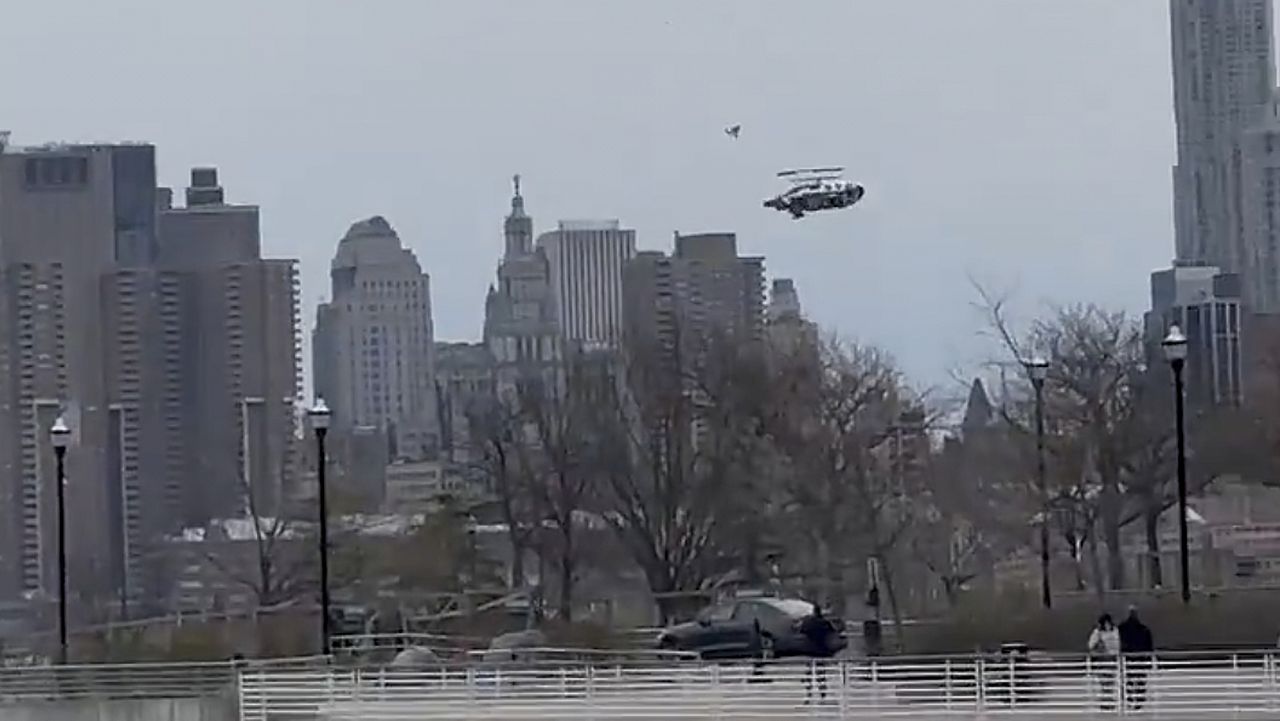

Nearly 23 years after the terror attack on the World Trade Center, people are still getting sick and dying from the toxins that enveloped Lower Manhattan.

But what remains unclear is what the city knew about air quality and the results of air quality testing in the aftermath. There’s an effort to get those documents, but the city so far has claimed it has nothing.

A spokesperson from City Hall had a different message.

An extensive public documents request filed in September asked for 28 separate items from seven different city agencies — each request having to do with the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center either in 1993 or 2001.

The inquiry asked for documents related to testing done in the early days after the attack, decision-making into reopening evacuated areas of Lower Manhattan, the correspondences and testing to reopen schools near the World Trade Center, materials for then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani's daily press briefings, and conversations about liability risk for the city.

Additionally, the request was for documents about testing of materials in the World Trade Center after the 1993 bombing and contingency plans set up in case of another terrorist attack.

So far, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection and New York City Emergency Management have responded. Both claimed they have no documents. NYCEM even called it a "diligent search."

However, a spokeswoman from City Hall confirmed otherwise to NY1.

"We are aware of requests to produce city documents on the aftermath of the attacks, which would require extensive legal review to identify privileged material and liability risk,” a statement attributed to the spokesperson read, in part.

“I mean it was disbelief. It didn’t make sense,” said Ben Chevat, when asked for his initial reaction when his request was denied.

Chevat was the longtime chief of staff for former Rep. Carolyn Maloney, who represented parts of Manhattan. He now runs a nonprofit, 9/11 Health Watch, which examines and checks to ensure legislation intended to help the victims of the 9/11 attacks aftermath are doing just that.

He has been one of the driving forces behind the Freedom of Information Law inquiry to get the documents from the city. The question he said he wants to get to the bottom of: What did the city know and when did they know it?

In total, 2,977 people died on Sept. 11 in the rubble of the World Trade Center.

Even more have died since because of illnesses from the chemicals they inhaled in the months after.

There are dozens of illnesses linked to what people inhaled in Lower Manhattan. Anyone who spent time below Houston Street from Sept. 11, 2001 to mid-2002 could be eligible for at least one 9/11 federal health program.

“I want to know who knew when how dangerous it was,” said Andy Ansbro, the president of the Uniformed Firefighters Association of Greater Manhattan.

The terrorist attack on Sept. 11 was his first fire he responded to. His dad, Michael Ansbro, also responded.

The elder Ansbro died of a 9/11-related illness. Andy has had skin cancer three times, another cancer linked to the aftermath.

NY1 found plenty of evidence the city should have air quality documents from the aftermath of Sept. 11.

A 2003 federal inspector general report said the DEP "conducted extensive ambient air monitoring for asbestos around Ground Zero and Lower Manhattan." The report even includes a letter from the DEP to downtown residents talking about all the testing they had done.

And in 2002, testifying before a U.S. Senate committee, the head of the DEP at the time, Joel Miele, told senators in his opening statement they had analyzed more than 3,000 outdoor samples and another 500 from the four schools near the World Trade Center.

At one point, he even encouraged people to go to the DEP's website to see the testing for themselves.

“It just doesn’t make any rational sense," Chevat said.

Less than a month after the attack, NY1 reported Battery Park residents were concerned going home because of the air quality.

"The quality of the air is acceptable," Miele told NY1 at the time. "Can I solve a problem if someone doesn't want to accept the data on the basis of what it is? No, I can't resolve those issues."

The DEP has said for asbestos exposure, there wasn’t a standard for outdoors, so they relied on indoor standards, which a significant majority of the testing met.

Still, Christine Todd Whitman, the head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency at the time, told New Yorkers the air was safe. She later apologized for that.

Back at the city level, an October 2001 internal memo NY1 has obtained from the Department of Health said the DEP believed air quality on some blocks near the World Trade Center was “not yet suitable for re-occupancy," and doing so would make the commissioner “uncomfortable.”

So lawyers on behalf of Chevat filed a lawsuit in New York State Supreme Court against the DEP, arguing the agency could not have done a diligent search for documents.

A city spokesperson said they are reviewing the lawsuit.

The initial FOIL request was sent to the New York City Department of Design and Construction, New York City Department of Environmental Protection, New York City Department of Health, Office of the Mayor, New York City Law Department, New York City Emergency Management, and the New York City Council.

Last month, the Mayor's Office requested more time to fulfill the FOIL request.

NY1 reached out to NYCEM for comment, since it also denied having documents. The agency has yet to respond as of Tuesday morning.

NY1's own reporting shows evidence of NYCEM's involvement in air quality decisions made in the aftermath of the attack. That includes NYCEM commenting on keeping One Liberty Plaza closed longer than anticipated.

"There were a few things that we weren't totally satisfied with," said Richard Sheirer, the head of the agency, to NY1 at the time. "And as soon as those areas are cleaned up and we are sure the [Department of Environmental Protection] and the other agencies are satisfied that the building is ready to open, we'll let it open as quickly as we can."

In March of 2002, the NYCEM was appointed as the lead agency for a task force on the air quality downtown. NY1 asked NYCEM in a request for comment how many hours were spent searching for documents relevant to the FOIL request.

“I think the city is skating all over the pond,” said Karen Klingon, whose brother died from brain cancer in 2020.

Rob Klingon lived just blocks away from the World Trade Center in 2001. While he left for a week after the attack, he returned believing it was safe to do so.

Klingon said she wants these documents to be released, not to assign blame, but to learn if another environmental disaster strikes Manhattan.

“Of course mistakes were made. That’s not what this is about," she said. "This is about helping the survivors.”

She said Rob did all he could to help survivors himself. She said his dying wish was for his brain to be donated to oncologists at Mount Sinai.

That's why she said she is part of the push to get these documents released, hoping to further his legacy by demanding answers from the government about the air quality.

_DNT_911_Air_Quality_Investigation_CLEAN_130267847_2447?wid=320&hei=180&$wide-bg$)