As voters in New Hampshire prepared to cast their ballots two months ago for the nation’s first primary election of 2024, there was already plenty of tension surrounding the early nominating contest.

State officials were defying the Democratic National Committee’s new primary lineup – an idea spurred by President Joe Biden – that stripped the Granite State of its long-held first-in-the-nation spot. As a result, the name of the incumbent Democratic president very much seeking another four years in the White House wasn’t on the ballot. Despite disappointment, local Democratic leaders were working to make sure Biden still won the state through write-in votes – even as they knew no delegates would be awarded at the party’s nominating convention this summer for their efforts.

On the GOP side, former UN Ambassador and South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley – then still in the race – was banking on New Hampshire keeping her presidential bid against former President Donald Trump alive.

Then, just days before voters were set to take to the polls, thousands received a call bearing a voice that apparently sounded like President Biden.

“It’s important that you save your vote for the November election….voting this Tuesday only enables the Republicans in their quest to elect Donald Trump again," the recorded call told voters.

The robocall, which used artificial intelligence to mimic Biden’s voice, was swiftly denounced as an illegal attempt to impact voting by the New Hampshire attorney general’s office. The White House quickly confirmed that Biden recorded no such message. (The incumbent president ultimately won the primary through write-in votes.)

Not long after, New Hampshire and federal officials tied two Texas companies to the call. The Federal Communications Commission swiftly banned robocalls containing AI-generated voices, allowing the agency to fine companies that deploy the practice. And it didn’t take long for the orchestrator of it all, political consultant Steve Kramer, to admit he hired a New Orleans street magician to create the call.

But the unambiguous and high-profile attempt to weigh in to an election through the use of artificial intelligence – a topic that took a starring role in Washington this past summer and fall – accelerated fears among some that New Hampshire’s robocall was, as Ilana Beller from the advocacy group Public Citizen puts it, “just the beginning.”

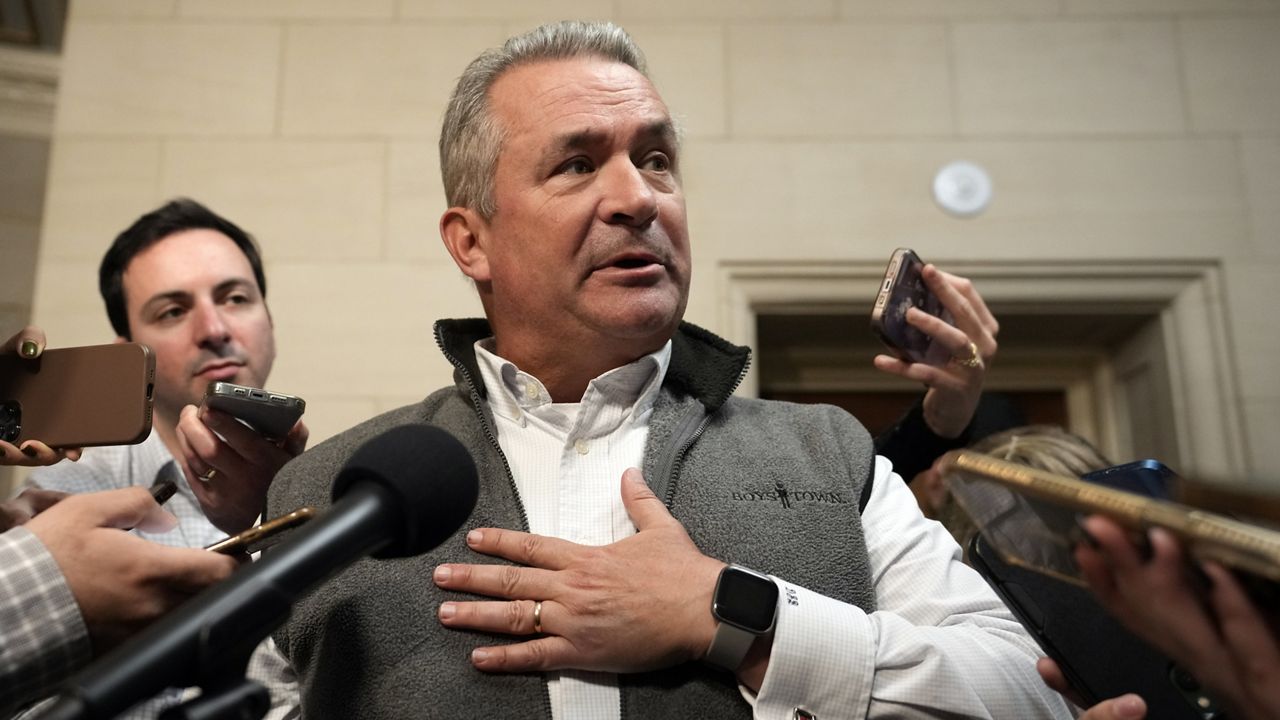

One of those concerned, New York Rep. Joseph Morelle – the top Democrat on the House Administration Committee – sent a letter to the Department of Justice in the immediate aftermath of the call asking for an investigation into the matter.

“This clear bid to interfere in the New Hampshire primary demands a thorough investigation and a forceful response from federal officials to deter further AI-based attacks that will disrupt American democracy and disenfranchise American voters,” Morelle wrote.

In a statement to Spectrum News last month, Morelle said he “commend[ed]” the FCC's decision to outlaw AI generated robocalls while indicating his concerns around the technology’s potential impact are not gone.

“However, more work is needed, including meaningful enforcement of existing state and federal laws applicable to this conduct, to ensure that election interference and voter intimidation - like we saw in New Hampshire - does not happen again,” Morelle said in a statement.

Last year, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s Capitol Hill testimony urging lawmakers to step in and regulate the emerging technology helped send the nation's capital into somewhat of an AI-frenzy.

Artificial intelligence and its potential future impact on a particular issue became the subject of hearings running the gambit of House and Senate committees and subcommittees. Some lawmakers reached out across the aisle to come together to propose AI-focused legislation. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., launched a series of AI forums, including one in the fall that saw some of the industry’s heaviest hitters, including Altman, X’s Elon Musk, Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg and Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, descend on Capitol Hill to brief the upper chamber.

On the other end of Pennsylvania Ave. Biden appeared determined to show his leadership on the topic, touting voluntary commitments from top tech firms to follow a set of guidelines when developing AI and, in October, signing a long-awaited executive order directing federal agencies to use their regulatory powers to safeguard against the technology.

Yet, despite the recent attention on regulation and lawmakers introducing several bills last year, legislation in Congress on the topic, especially as it pertains to elections, has not received much movement.

“It is legal in most states to create these deepfakes,” Daniel Castro, vice president at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, said. “Anyone in an election environment knows people will do whatever it takes to win, especially if it's legal.”

AI-generated deepfakes refer to an image or recording of someone that has been convincingly manipulated to depict something that was not actually said or done.

Before this year, only five states had some version of a law on the books prohibiting or restricting their use to depict a candidate – California, Texas, Washington, Michigan and Minnesota, according to Public Citizen, which tracks such legislation. The latter three of those states passed the legislation last year while California and Texas did so in 2019.

“First, we have to address the question of: 'Is this going to be a lawful tool that campaigns can use or is it not?'” Castro said.

Given that it's unlikely Congress would enact a law to answer that question before November – as Beller, who is the organizing manager for Public Citizen’s Democracy campaign, argued – states across the country are taking the matter into their own hands.

In just the first two-and-a-half months of 2024, seven state legislatures – including Florida, Idaho, Indiana, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah and Wisconsin – have passed bills regarding deceptive or synthetic media in election and campaign communications – although some still await a governor’s signature to become law.

This year's passed bills means about a dozen states have legislatures that have passed legislation on the topic, about eight months out from the 2024 general election.

And dozens of additional pieces of legislation have been introduced or are already working their way through state houses (about 10 states have a bill that has passed one chamber.)

One of those is a bill in California introduced by Democratic Assemblymember Gail Pellerin, who spent years as the chief elections official in Santa Cruz County.

“I've been in this field a long time and I’ve seen the impact of just the internet and what can happen in an election,” she said.

California’s 2019 bill prohibits the distribution of deception audio or visual media of a candidate within 60 days of an election, unless the content includes a disclosure that it has been altered. Pellerin’s bill, which has so far just been introduced, seeks to ban advertisements or election communication that contains materially deceptive or digitally altered images, audio or video with the intent to influence an election – whether or not it's disclosed – 120 days before an election and in some cases 60 days after an election.

“My bill, 2839, says that you just can't do it,” Pellerin said. “It's gonna be prohibited, any of these AI-altered mailers, robocalls, video ads that are materially deceptive – we're saying no, you cannot do that.”

She also noted her legislation bans any such material that could “influence an election” rather than specifying the content would have to be about a candidate. That means, she said, altered information about voting machines or a similar topic could be covered by her bill.

The bills passed or introduced across the country range in their wording, approach to the issue and the degree to which the use of artificial intelligence is restricted. The number of days before and/or after an election in which the law applies also differs.

Pellerin noted she included her 120 and 60-day caps in a bid to protect against freedom of speech challenges – which Beller said she assumed was the driving reason other lawmakers added time specifications in theirs.

“We're really treading carefully around the first amendment and we do not want to have anybody questioning what we're doing and claiming that it will violate the first amendment,” Pellerin said. “So we're putting up this timeframe as a guardrail.”

But Castro made the case that the first amendment argument is what makes the topic “so hard to regulate” in the first place, saying there should be more of a focus on the “core issues” rather than just the technology.

“What we really want it to say is, campaigns should not be engaging in deceptive behavior, whether that's using AI or not,” he said. “And so I think, taking this a little bit away from the technology and focusing on the core issues, we need to have clear rules on transparency … and political activity.”

“The average individual doesn't know when they should or shouldn't trust information and until we address that kind of basic digital literacy, media literacy issue, no amount of regulating the technology or regulating the social media platforms, will really have much of an impact,” he said.

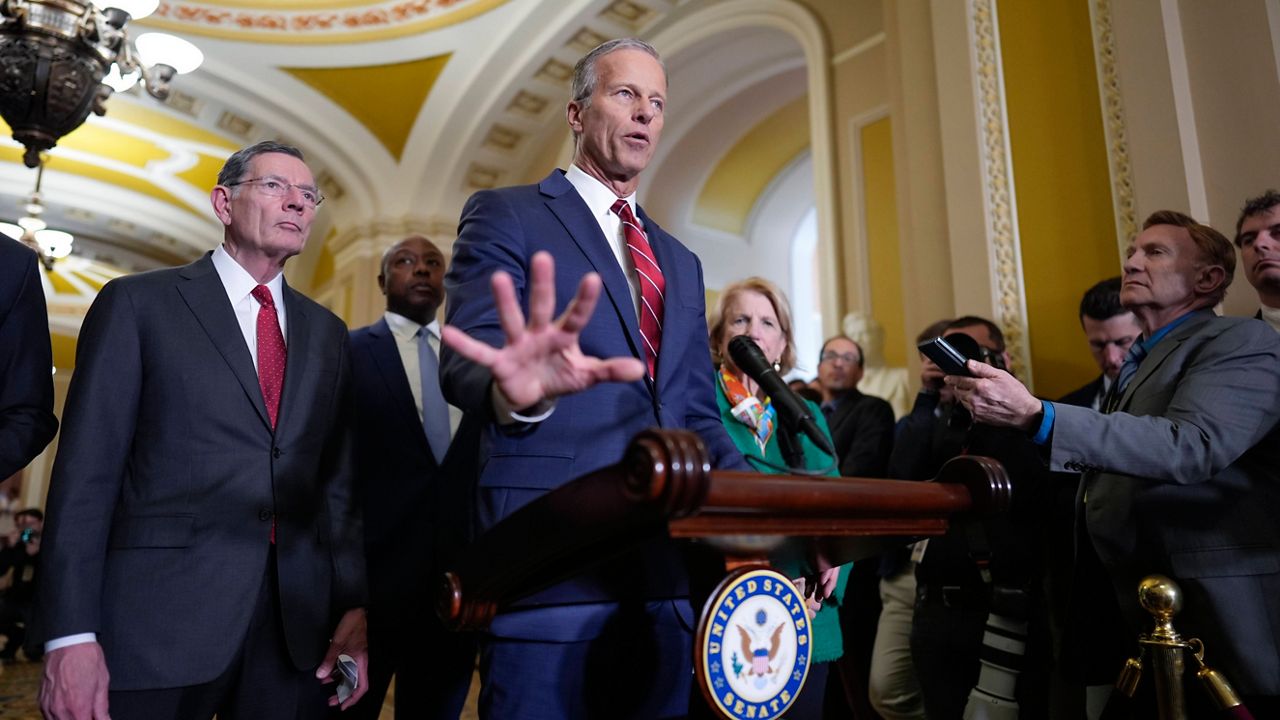

Last year, a bipartisan group of senators introduced legislation that would ban the use of AI to make deceptive content falsely depicting federal candidates in political ads and just this month two of those senators introduced another bill seeking to provide guidelines on AI to election offices.

Despite that bill being introduced, Beller – who also said Public Citizen petitioned the FEC for rulemaking around regulation of the issue – believes regulation at the federal level before November is unlikely, and emphasized the significance of states taking action.

“All of that kind of leads to the need for states to take action right now in order to ensure that they are covered ahead of the 2024 election,” she said.

“I think that if states have not legislated on this issue this year, unfortunately, they're going to see most likely in the upcoming election that this is an issue,” she added, “and they will feel like they have to legislate on it next year.“