The Biden administration’s crusade against "junk fees" — the term it uses to describe hidden fees that pile costs onto transactions — has turned once again toward financial institutions and "highly profitable" fees imposed on overdraft loans.

The Consumer Finanical Protection Bureau has proposed a rule addressing overdraft loans, seeking to close a loophole that has allowed large banks and financial institutions to take in billions of dollars in fees each year. The rule change is estimated to create as much as $3.5 billion in fees for consumers each year — or an annual average of $150 for each of the 23 million households that pay overdraft fees.

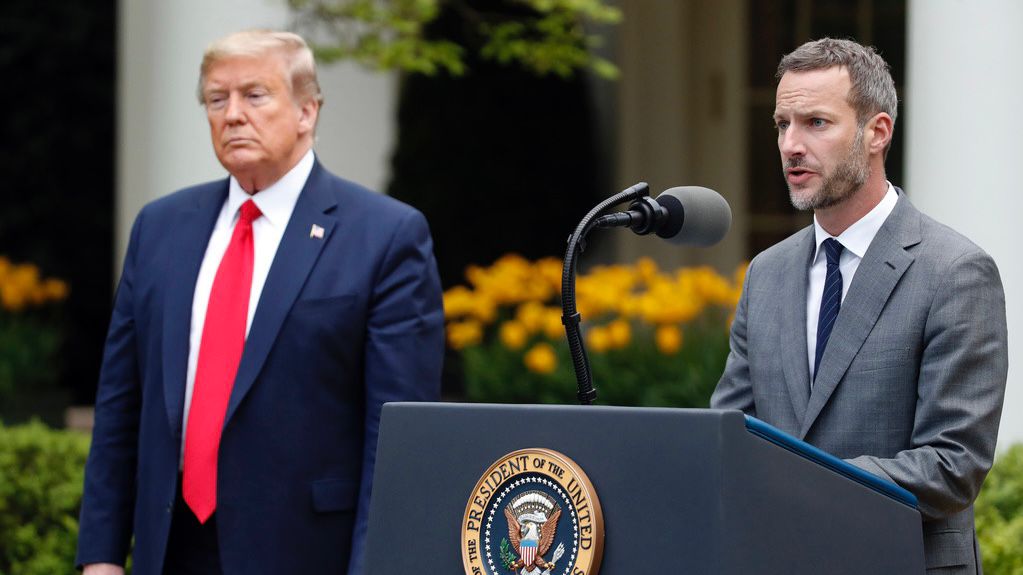

"For too long, some banks have charged exorbitant overdraft fees — sometimes $30 or more — that often hit the most vulnerable Americans the hardest, all while banks pad their bottom lines," President Joe Biden said in a statement. "Banks call it a service — I call it exploitation."

In recent years, the federal government has sued banks, including Regions Bank, TD Bank and Wells Fargo, for deceptive practices, illegal surprise overdraft fees and schemes that forced new customers to sign up for "free" overdraft services.

The rules proposed by the CFPB would limit the amount a bank or lender could charge in overdraft-related fees, tying the fees to either a flat, government-determined amount (with ranges proposed between $3 to $14) or a "breakeven" amount related to the cost of providng overdraft protection.

Proposed rules would also require lenders to treat overdraft loans — the act of a financial institution covering the balance of a transaction when an account is overdrafted, rather than shutting the transaction down immediately — like credit cards or other loans. Lenders could be required to provide loan education and information to customers, and could provide customers with cheaper sources of credit, as with certain credit cards.

Junk fees can generally be categorized as the small, largely unavoidable charges that are tagged on to transactions — think of service fees for buying tickets online — and increase the final cost of goods or services beyond what a consumer expects to pay.

"Companies shouldn’t be able to sneak charges onto your monthly statement, or tack on fees for things you didn’t ask for after youv’e already committed to a service or purchase at a lower cost," said Lael Brainard, chair of the Whie House National Economic Council. "Not only do those hidden fees inflate prices, they make it difficutl to accurately comparison shop and impede competition."

Overdraft protections began as a way to protect banks, consumers and businesses in the pre-digital era, when check cashing and billing was subject to the occasional unpredictability of mail services. Unintended, occasional overdrafts were cleared on a case-by-case basis, and banks would clear overdrafted accounts with a small fee. An exemption to the Truth in Lending Act of 1968 cleared overdraft loans from being treated as consumer credit.

But, as debit card transactions became more frequent — and small overdrafts became more prevalent — banks charged more and costlier fees. Modern overdraft fees now cost as much as $35 per transaction at some institutions, "even though most consumer debit card overdrafts are for les than $26 and are repaid within three days. This translates to pricing, in APR terms, of around 16,000%," CFPB Director Rohit Chopra told reporters.

The proposed rules would only affect large institutions withmore than $10 billion in assets, and will be in a comment review period until April 1. The final rules aren’t expected to go into effect until October 2025.

_crop)