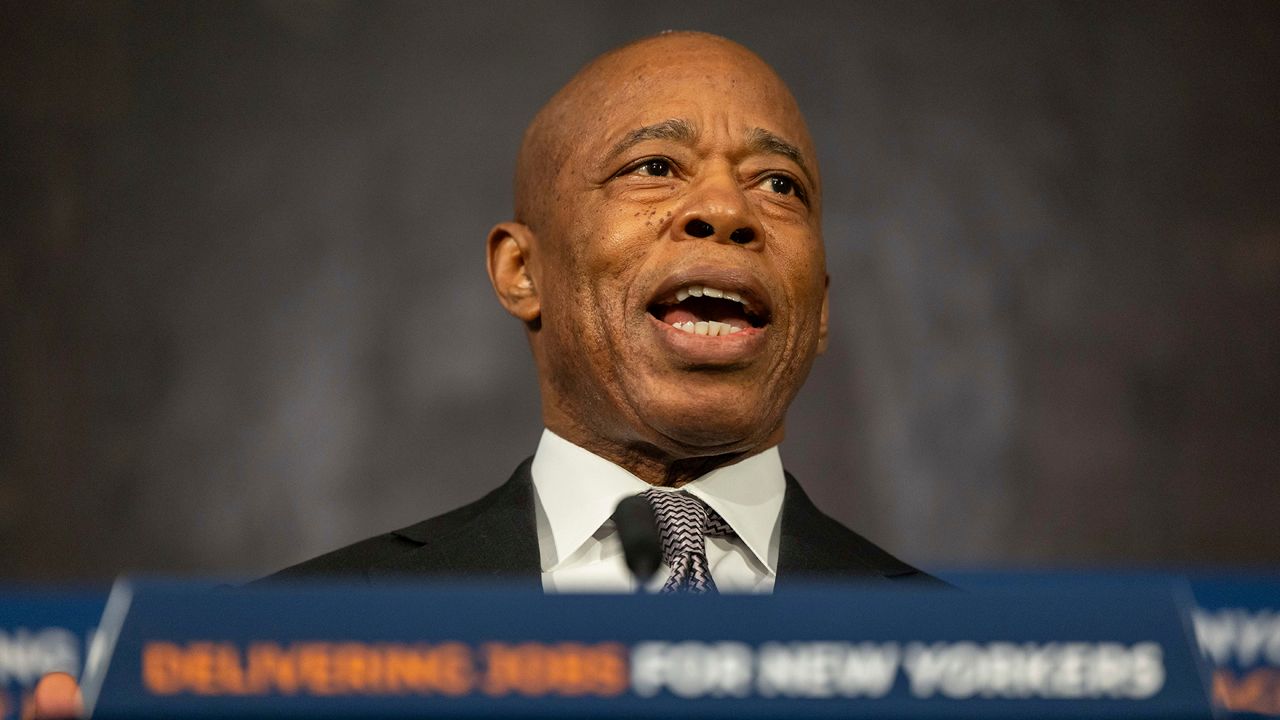

One year ago to the day, Mayor Eric Adams unveiled a controversial directive: city-led “specialized intervention teams” would be tasked with involuntarily hospitalizing people who appeared to be dealing with mental health issues so severe that they could not meet basic living standards.

The plan centered around a more expansive interpretation of state law, which allows a person to be involuntarily hospitalized if they pose a danger to themselves and others.

What You Need To Know

- One year ago, Mayor Eric Adams unveiled a controversial directive that allowed city-led teams to involuntarily hospitalize people who appeared to have severe mental health issues and could not "meet basic needs"

- At a news conference Wednesday, Adams said the plan was working as intended, despite criticism from opponents who said it could potentially criminalize homeless people and those suffering from mental health issues

- Fifty four people on the city’s list of the 100 “hardest to reach New Yorkers living on city streets” are now either staying in supportive settings or being treated in hospitals, Adams said

Critics immediately pushed back, saying the mayor’s new policy could potentially criminalize homeless people and those suffering from mental health issues. The Adams administration on Wednesday, however, said the policy was working as intended.

“One year later, we are proud to stand here and say early results show our plan is working,” Adams said at a news conference. “We have housed and helped a significant number of those most in need with care and support — care that helped them recover and reunite with family and friends.”

Fifty four people on a set of city lists of the 100 “hardest to reach New Yorkers living on city streets” are now either staying in supportive settings or being treated in hospitals, Adams said, representing a 145% increase from the previous year.

The people were on the lists because of a variety of factors that included mental health issues or substance abuse problems.

Brian Stettin, City Hall’s senior advisor on severe mental illness, said a “significant” number of those 54 people entered the system via involuntary removal. Of the 54, 14 are currently hospitalized, with the goal of moving them into “less restrictive” supportive settings, he said.

“We wanted to zero in on those 100 unsheltered individuals who are chronic unsheltered, dealing with severe mental health issues to the point that they can’t take care of themselves,” the mayor said. “We were extremely clear to New Yorkers that we were not going to allow people to live in undignified way on our streets during inclement weather and just during a normal course of doing business.”

An NYPD official said on average, police officers are removing 137 New Yorkers from the street weekly. That total also includes people in private homes and/or shelter, according to City Hall.

“This point about data is so important, and we’re happy that in this administration we’re now going to keep data in a way that we can drill down on these answers,” Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services Anne Williams-Isom said.

Asked if the city was tracking the outcomes of those who were removed, Adams deferred to Stettin, who said officials were “tracking them very closely.”

Officials emphasized that removals are one tool in the overall plan for helping those sleeping outside.

“Make no mistake about it, with every individual, hospitalization is not the end in itself. It is a means to an end,” Stettin said. “And we’re working really hard with each of those folks to try and get them back into a community placement.”

As part of the update, Adams announced additional efforts the city is taking to help those struggling like increasing the number of psychiatric beds to 1,000 and stepping up training of clinicians and first responders.

And yet, some statistics — including the demographics of those involuntarily removed — are still unavailable. Adams also acknowledged that the city was not previously tracking involuntary hospitalizations.

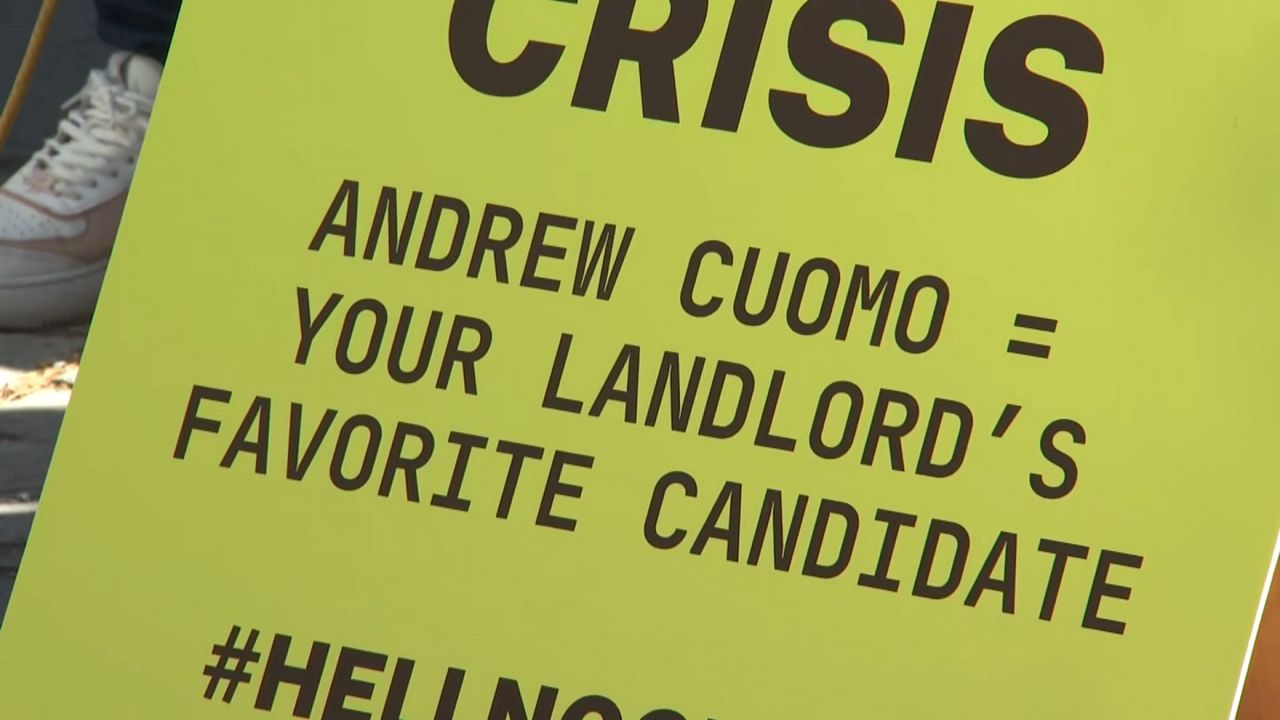

Critics on Wednesday took aim at the mayor’s victory lap, pointing out that the lack of data available raises transparency and accountability concerns.

In a statement released Wednesday afternoon, New York Civil Liberties Union executive director Donna Lieberman, who previously criticized the plan, said the Adams administration “offered no data on [the plan’s] implementation, including whether people of color are being disproportionately targeted.”

“Forcing vulnerable people into treatment was an old, failed strategy when Mayor Adams announced it a year ago, and it still is,” Lieberman said. “Despite the Mayor’s victory lap, a policy that criminalizes New Yorkers experiencing mental health challenges and homelessness is not help.”

One New Yorker who has been helped is Terry Brown. NY1 first caught up with him in July, when he had just gotten a housing assistance voucher known as CityFHEPS. He is living in a Safe Haven in the Bronx while he looks for permanent housing.

Brown was living on the streets for many years, struggling before he got help from homeless advocate Shams DaBaron.

“I didn’t take the step that I was told to take. When Shams sat down with me and told me to listen here man, take that step man, don’t be scared,” Brown said on Wednesday. “You have to stop worrying about what the people on the outside are thinking, or how people are looking at you or where you’ll be at. Take that step man, it’s the road to success.”

Separately, Adams said that under the subway safety plan, the city has been able to connect 6,100 New Yorkers to housing.

_PKG_Hudson_Yards_Zoning_Hearing_CG)