Earlier this week, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee, who is overseeing former President Donald Trump's election trial in Georgia, granted a request from four local Atlanta news stations to allow cameras in the courtroom.

In doing so, the Georgia case, which has already set some historic firsts, sets another milestone: Of Trump's four criminal cases, it will be the only one that could be televised.

Cameras are not allowed in federal courtrooms, nor are they allowed in New York courtrooms in most instances; the judge in the New York case, which involves alleged hush money payments to an adult film star during the 2016 presidential campaign, denied a request to allow cameras into the courtroom.

Despite these rules, there have been growing calls for Trump's trials to be televised.

Earlier this month, a group of 38 House Democrats sent a letter to Judge Roslynn Mauskopf, secretary of the Judicial Conference, the national policymaking body for the federal courts, asking for an exception to be made in both the Washington-based election conspiracy case as well as the Florida-based case involving Trump’s handling of classified documents, citing the “the extraordinary national importance to our democratic institutions and the need for transparency.”

“Given the historic nature of the charges brought forth in these cases, it is hard to imagine a more powerful circumstance for televised proceedings,” wrote the members of Congress, led by Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif. “If the public is to fully accept the outcome, it will be vitally important for it to witness, as directly as possible, how the trials are conducted, the strength of the evidence adduced and the credibility of witnesses.”

Advocates for more transparency are hoping the contrast puts pressure on federal officials to change the rules.

“We live in an age of information, but also we live in an age of misinformation,” Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Courts, an advocacy group that seeks to reform the federal judiciary system, told Spectrum News. “The ability of the American people to see the courtrooms across the country, whether federal, state, municipal ... the action inside live as it unfolds will be a huge benefit to the civic health of the country.”

In the Georgia case specifically, Roth believes having video will help Americans keep track of the multiple defendants, many of whom are relatively unknown, especially outside of Georgia.

“Trying to prove the influence of an election under RICO statutes, I think there are a lot of moving parts,” he said, predicting that might prompt people to re-watch certain parts to better understand the arguments being made by each side.

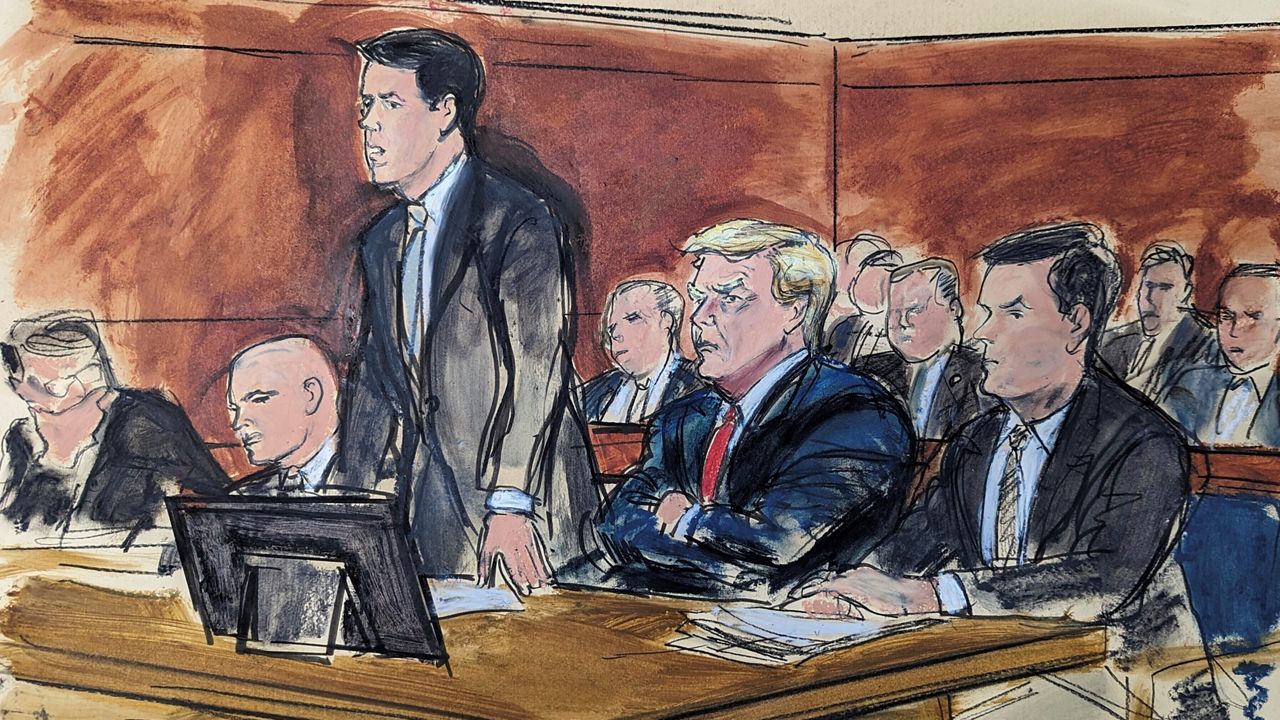

"The video footage tells the story,” Margaret Talev, the director of the Syracuse University Institute for Democracy, Journalism and Citizenship and a senior contributor at Axios, explains. And without it, “you’re relying on courtroom sketches, you’re relying on the reporter’s analysis of things.”

That’s something that the public won’t be able to do when Trump stands trial in Washington, D.C., for federal charges also related to election interference, nor will they be able to when the former president appears in Florida for the Justice Department's case about alleged mishandling of classified documents. A judge in Florida denied a request from media outlets to allow cameras in the courtroom in that case in June.

Federal courts maintain a strict ban on cameras of any kind at criminal trials. Supporters say it prevents grandstanding by attorneys and offers protection for witnesses.

“Georgia, intentionally or not, is going to serve as a test case for the future arguments about whether or not to expand cameras in federal courtrooms,” said Talev. As the two high-profile cases go before the juries, “we will see in real time the real difference between what kind of information the public gets, how the public understands the cases, and also how both the prosecutors and the defendants in these cases can use cameras, when they do exist, to tell their story.”

Steven Brill, founder of Court TV, wrote in a New York Times op-ed earlier this month that in order for the election conspiracy trial in Washington to be broadcast on television, the Judicial Conference, which is chaired by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts, and the judicial council of the District of Columbia Circuit would have to suspend their own rules, and the Supreme Court would need to amend the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.

But Brill argued it would be worth the effort. He said the proceedings would likely be the “the most consequential trial in the nation’s history.”

“The last thing our country and the world needs is for this trial to become the ultimate divisive spin game, in which each side roots for its team online and on the cable news networks as if cheering from the bleachers,” he wrote.

Roth is optimistic that the Georgia case will make a compelling argument for more access, but he does not expect an immediate policy change from the federal courts.

“Until we get a generational turnover, we may not see a lot of movements in this area, unfortunately," he said.