Opponents of school safety agents in schools, including some New York City students, went before the City Council Wednesday to testify about why they feel the agents do more harm than good.

It comes on the heels of three separate shootings near Manhattan schools just a day ago — two of which left two teens and an adult injured.

Still, critics of school safety agents, including Brooklyn high school student, Nile Borja, feel the agents criminalize students, even those who may not have a history of criminal behavior.

What You Need To Know

- Critics of school safety agents believe they add a militarized component to school safety, disproportionately target students of color and make them feel less safe

- The mayor's budget proposal currently allocates money for more school safety agents than are currently in city schools but less than on-the-job school safety agents before the pandemic

- Supporters of school safety agents believe schools need more of them, particularly as shootings near city schools are on the rise

When Borja is not swimming with his swim team, doing homework or making music, he’s hanging out with his friends.

“I think I’m a good kid,” Borja said. “I try my best not to get into any trouble in school.”

However, Borja said trouble found him one day when he accidentally left a laser toy he uses to play with his cat in his backpack, which triggered the security scanner at his high school and sparked the attention of school safety agents.

“They took me to their police office in school and started interrogating me,” he said. “They asked me why I brought it in, what I used it for.”

Borja said the experience made him feel terrible.

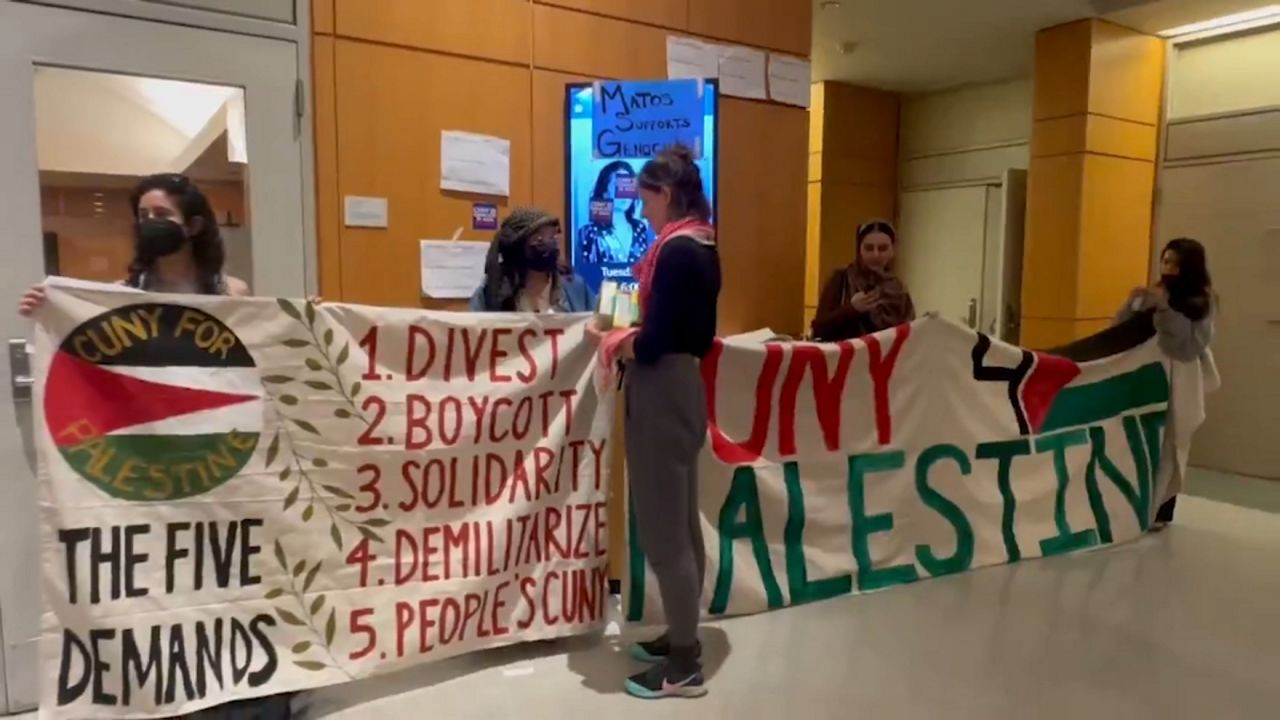

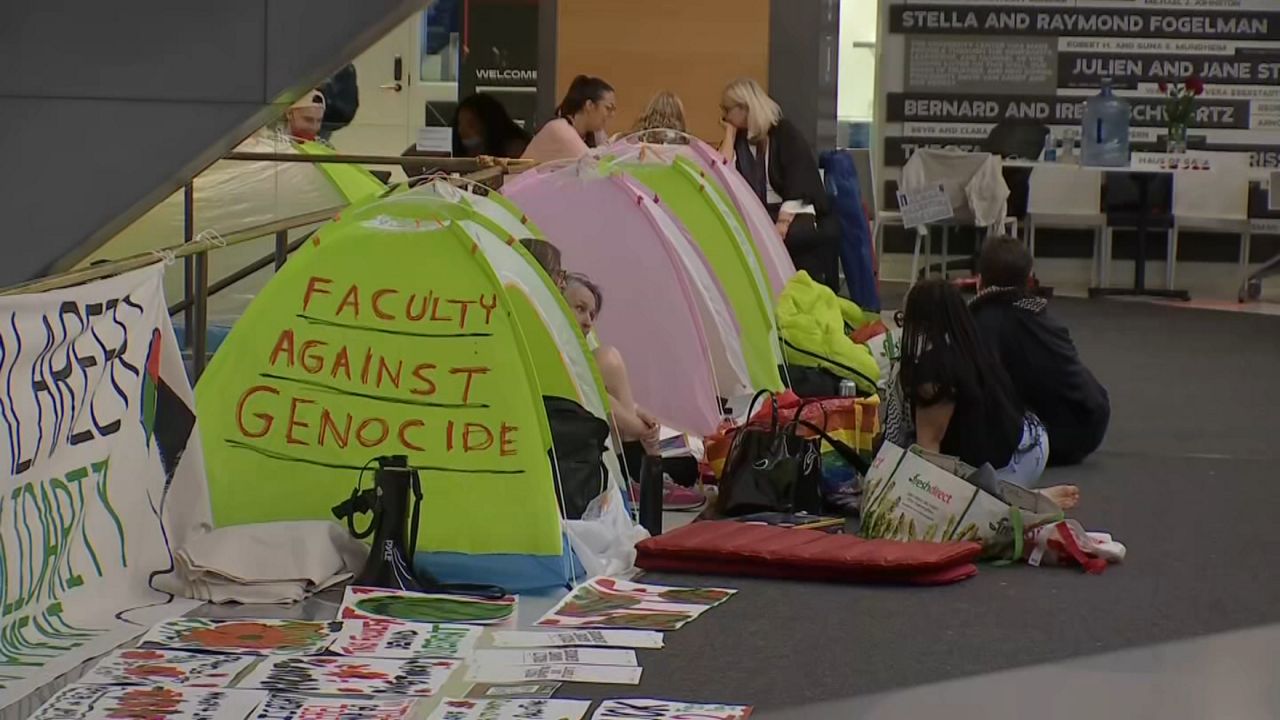

He and his friends here are part of the Urban Youth Collaborative, which is calling on Mayor Eric Adams to cut funding for school safety agents from his budget. They believe they add a militarized component to school safety, disproportionately target students of color and make them feel less safe.

The mayor’s budget proposal currently allocates money for more than 4,400 school safety agents. That would be an increase from the roughly 3,800 current on-the-job school safety agents in New York City Schools, though fewer than more than 5,000 before the pandemic.

Borja and other advocates would rather see the funds invested into practices that focus on students’ well-bring, such as restorative justice measures that emphasize peaceful conflict resolution over punitive discipline.

“Restorative justice, mental health, counseling, therapy and it’s all to help growth and learning of a student,” Borja said.

Supporters argued as much before City Councilmembers during a preliminary budget hearing on Education Wednesday.

However, Chien Kwok of the School Safety Coalition & Community Education Council for District 2, disagrees.

“Theres a policy of using restorative practices, which actually don’t work,” Kwok said. “It has proven to be a failure. There’s got to be consequences immediately and support for the kids who are acting out, who are disruptive and violent.”

Chien Kwok is a father of two and says — even though school safety agents don’t carry guns or handcuffs and are not cops — they do make schools safer.

“My daughter always hugs the safety agents at school,” he said. “We feel safe with them. We feel safer with them and we need to support that and increase them.”

The number of schools safety agents has dropped since the pandemic. The mayor has not indicated that he intends to increase the number of school safety agents to pre-pandemic levels.

The City Council and the mayor have until the end of June to agree on next year’s budget.

Editor’s note: School safety agents at public schools are equipped with handcuffs. A previous version of this story was incorrect.