Dr. Anthony Fauci will step down from his roles as the president’s chief medical adviser and top infectious disease expert at the end of this year, closing out more than half a century in public service, defined by his legacy as a leading physician, researcher and national voice on diseases in the United States.

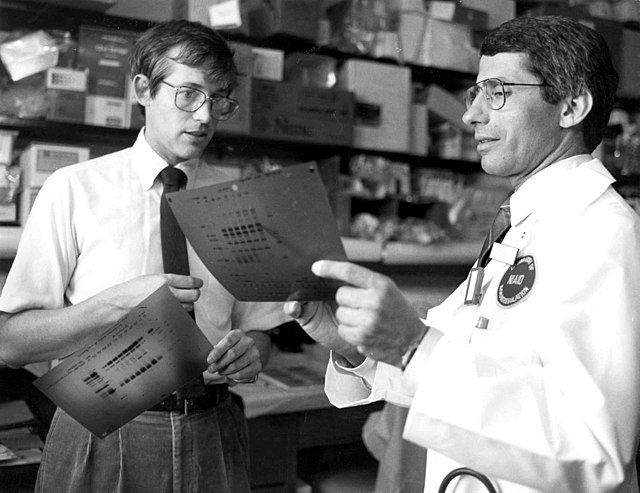

Though his national presence ascended in 2020 with the emergence of COVID-19, Fauci has spent more than half his life working for the U.S. government, after he first began in 1968 as a clinical associate at the National Institutes of Health, under Lyndon Johnson.

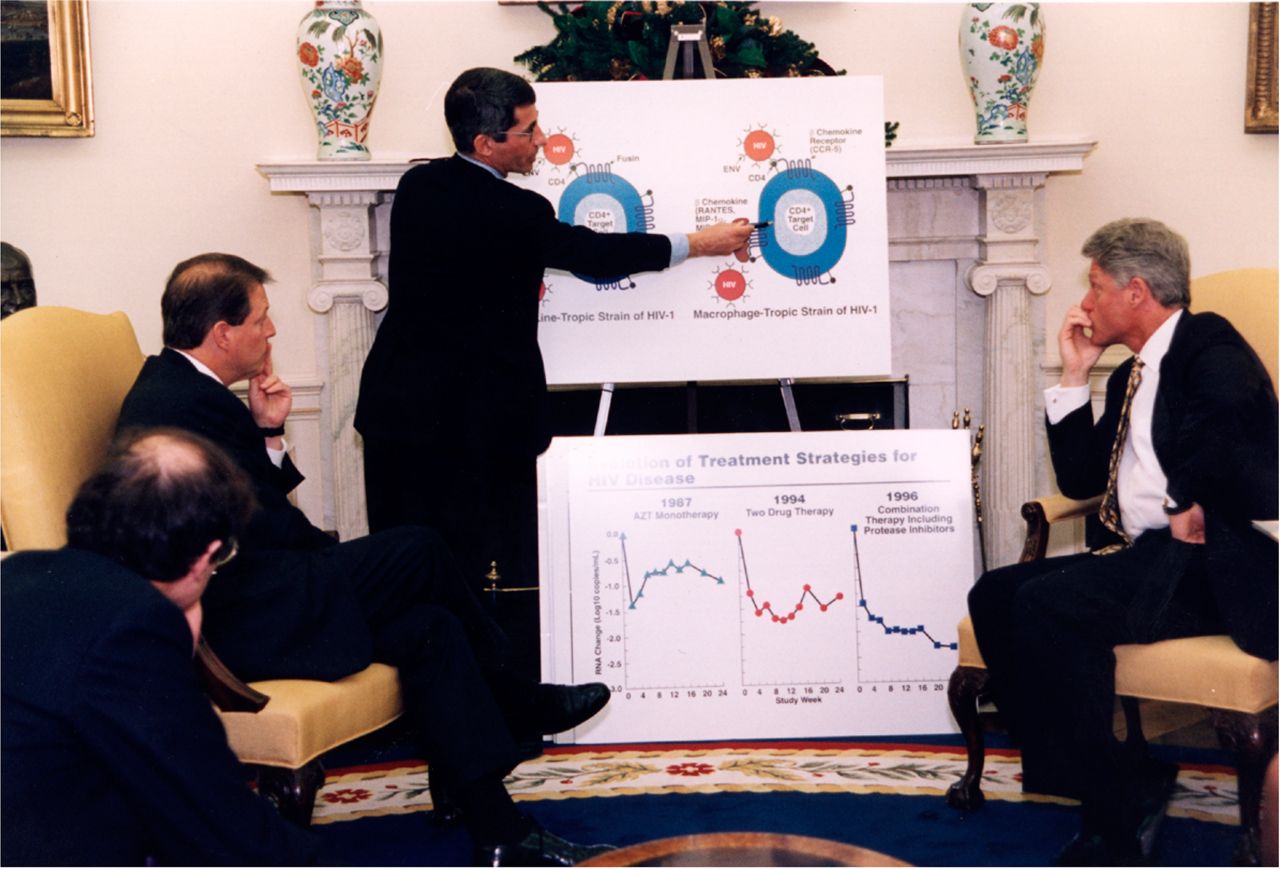

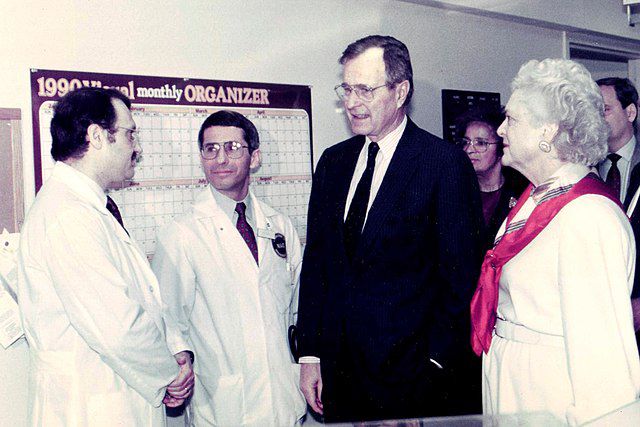

The Brooklyn-born infectious disease expert has since personally advised seven other presidents, Democrat and Republican, with the bulk of his legacy being his research on HIV/AIDS and his contributions to the federal response.

When he steps down, he ends an extraordinary run of 38 years as the director of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, which is housed at the NIH.

“It's been a very, very long haul,” Fauci, who turns 82 this Christmas Eve, said in a November interview with Spectrum News. “But there have been phases during those decades that things were done – not alone with a lot of help from a lot of very good people – that I feel very good about.”

And during his final appearance at a White House briefing, he noted that COVID-19 was just a small part of a career during which he says he "never left anything on the field."

"If they want to remember me, whether they judge rightly or wrongly what I’ve done, I gave it all I got for many decades," Fauci told reporters.

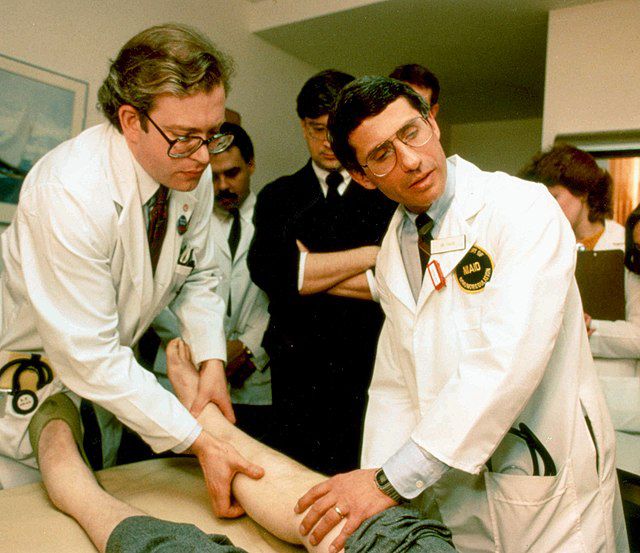

One of the things Fauci has said he’s most proud of are the life-saving treatments that came from his dual responsibilities of research and patient care at the NIH.

In a recent opinion essay for the New York Times, Fauci wrote that he never aspired to a high-level position in a presidential administration and “relished my identity as a hands-on physician and clinical researcher.”

“Most of the drugs that have now been used to be life-saving combinations of drugs for people who are living with HIV, that has saved millions of lives,” he told Spectrum News.

Fauci received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2008 from President George W. Bush, under whom he was one of the principal architects of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a program that is credited with saving millions of lives in more than 50 developing countries.

Though he’d served decades as the nation’s top infectious disease expert by 2020, he first became known to most Americans as COVID-19 transformed the country that winter. He frequently did media interviews about the virus and appeared at White House briefings alongside the former president Donald Trump and his group of coronavirus advisers.

Faced with a rapidly spreading and dangerous virus, Fauci and other advisers grappled with how to instruct the public on an evolving situation.

He first portrayed masks as ineffective for the general public, saying there was “no reason” for people to wear them, reversing course a few weeks later. In February of 2020, he said Americans’ risk of catching COVID was “low” while also warning it could become a pandemic.

As the virus spiked, Trump’s medical advisers eventually decided on drastic steps like requiring face masks and limiting the size of public gatherings.Those changes disrupted everyday life and created a major economic downturn.

That eventually led to friction with President Trump, who in October of 2020 called Fauci a “disaster” and said people were tired of COVID.

More broadly, Republicans have criticized Fauci’s guidance as inconsistent and harmful. But, he says, that guidance saved lives.

“I don't belong in any affiliation, to any party, and I stay away from politics and stay with science,” he said “The people who want to politicize science have politicized science. I have not politicized what I've done.”

And as for the sometimes-confusing changes in his advice over the first stages of the pandemic? It’s the nature of a new virus, he says.

“We were dealing with truly a moving target,” the NIAID director said at the White House last month.

“You have to make [recommendations] on the basis of the information that you have at that time,” he added, giving advice to health officials moving forward: “We’ve probably got to do a better job of, when we talk to the public, [explaining] that this is a dynamic situation that could change.”

His newfound notability as a household name cut both ways, making him a target for critics.

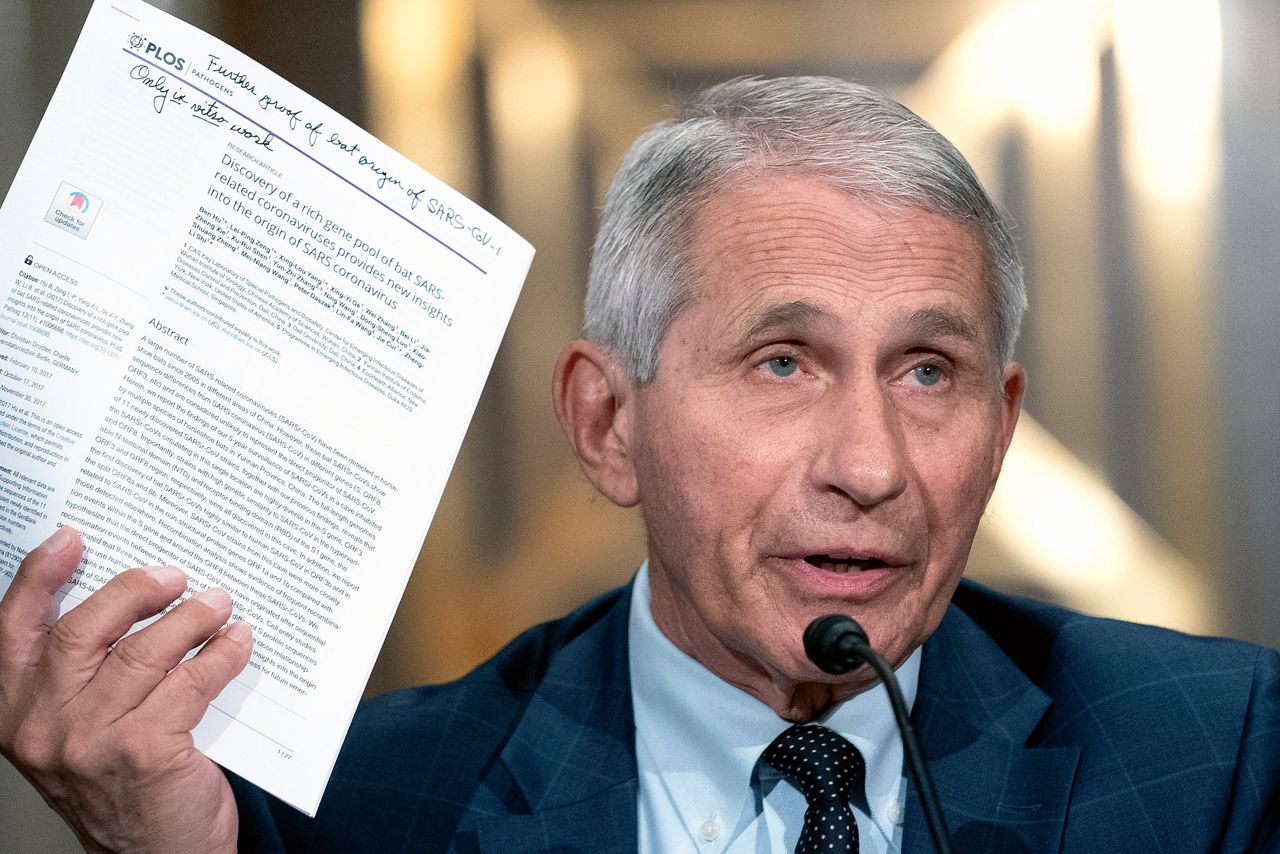

One such detractor, Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, has come after the NIAID director in several congressional hearings, accusing him of funding research in China that led to the coronavirus, suggesting it leaked from a lab in China three years ago. He falsely accused Fauci of being responsible for millions of deaths.

Members of Paul’s party in the House have indicated they’ll subpoena the disease expert once Republicans take the majority in 2023.

“The most important thing is that we find the origin of the virus,” Paul told Spectrum News.

Fauci said at his final White House press briefing last month that he will cooperate fully: “We can defend and explain and stand by everything that we’ve said. So I have nothing to hide.”

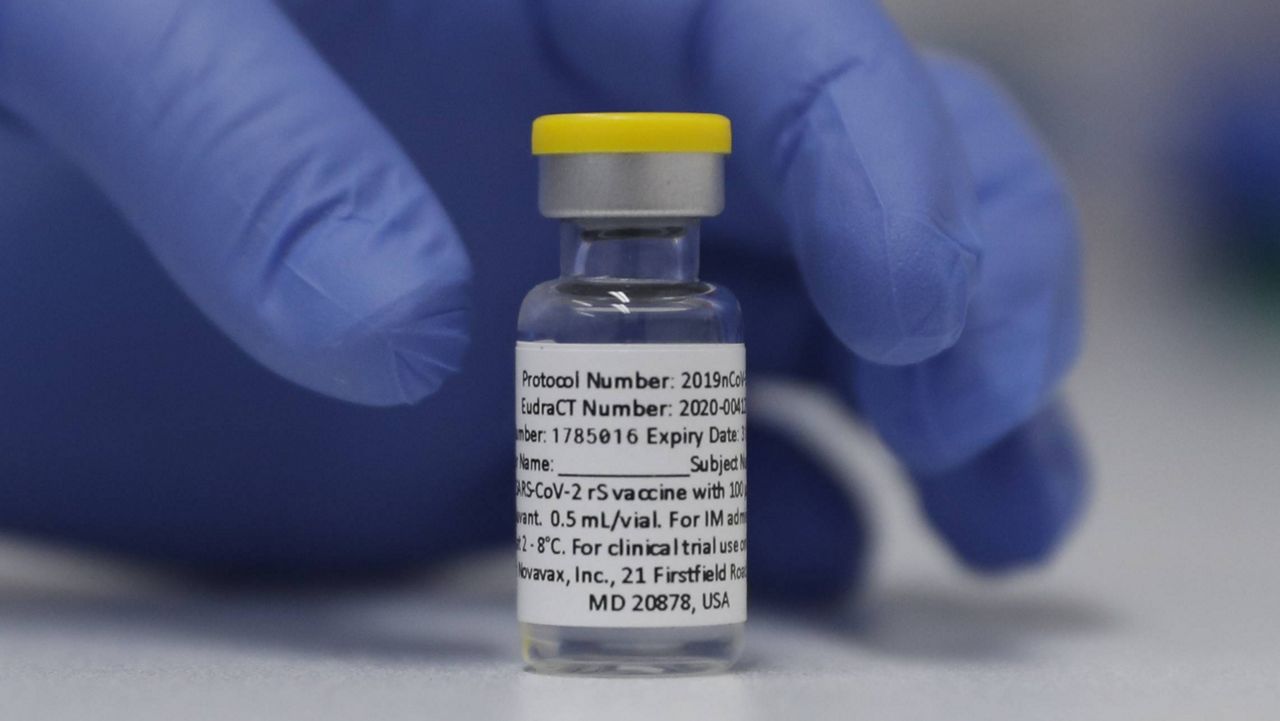

Standing at the White House podium one last time this November, Fauci – who has served as President Joe Biden’s chief medical adviser since day 1 of his administration – urged Americans: Get your updated COVID-19 shot.

He ticked through the data about the vaccine, a practice of his since the virus first appeared in 2020.

“We know it’s safe, and we know that it is effective,” he said.

It was just one of many messages that Fauci delivered to the American people throughout the pandemic, and over his tenure in public health. He’s always spoken the “unvarnished truth” to presidents, Fauci wrote in the New York Times.

After the friction and rejection of COVID protocols in the Trump administration, he took the podium at the White House for the first time under Biden and called it “liberating” to talk openly about science.

In fact, that’s what Fauci names as his biggest challenge in the last few years.

Watching, as a physician, as misinformation and political views transformed medical advice into something partisan, leading to thousands of American deaths.

“As a physician, it pains me,” he said. “Because I don't want to see anybody get infected. I don't want to see anybody hospitalized. And I don't want to see anybody die from COVID,” he added.

“Whether you're a far-right Republican or a far-left Democrat doesn't make any difference to me. I look upon it the same way as I did in the emergency room in the middle of New York City when I was taking care of everybody that was coming in, off the street.”

When he steps down at the end of 2023, Fauci doesn't call it a retirement but rather a continuation of his work.

He hasn’t shared with the public or press what he plans to do next, noting when asked by Spectrum News that it’s “not appropriate” to negotiate a new job while still serving the president.

One thing is for sure – his next steps won’t involve politics.

“I want to continue in the public arena. I want to be writing and lecturing about public health issues, about global health issues, perhaps inspiring younger people to get involved in public service,” he said.