Federal agencies implementing the Biden administration’s $1.2 trillion infrastructure law have now all named senior officials to oversee their department’s portion of spending, a top budget official told Spectrum News, a key directive from the administration as the White House seeks to prevent wasteful or fraudulent spending that sometimes plagues large federal programs.

About six months into the law’s implementation, $110 billion in funding is heading out the door and more than 4,000 projects are underway across the United States, the White House said, from new high-speed rail routes in Florida to electric vehicle charging stations in Wisconsin.

Now at the federal level, agencies are mainly accountable for tracking the money as it flows out to states, cities and individual projects, according to guidance from the White House budget office.

The first step was appointing a “senior accountable official” to oversee implementation.

“The agencies already have their accountable officials in place, and they're meeting on a regular basis,” said Jason Miller, deputy director for management at the Office of Management and Budget.

“[Agencies] are the accountable entities to deliver on their programs,” he added.

The Department of Transportation, which is in charge of more than $283 billion of the $550 billion in new money, first named their implementation director, Katie Thomson, in December, shortly after the White House tapped former New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu as the law’s top coordinator.

Over the next five years, the law is expected to provide $110 billion in new dollars for roads, highways and bridges, $66 billion for rail, over $63 billion for clean drinking water, $65 billion for broadband, $39 billion for public transit and more, according to the White House.

Also among the White House’s initial instructions to agencies is a call to work with inspectors general — the federal watchdogs in charge of identifying and investigating waste, fraud or mismanagement within a department.

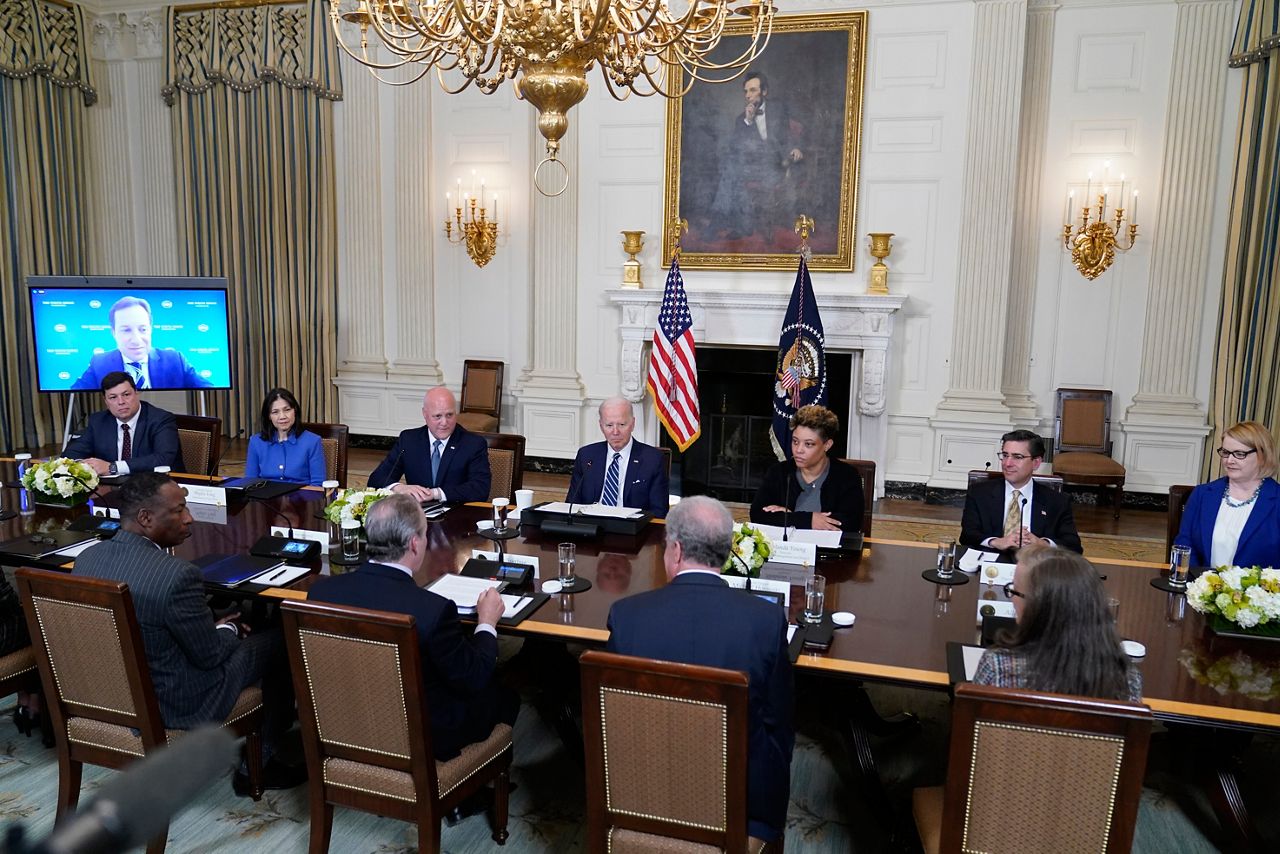

President Joe Biden met with those inspectors general at the White House in late April to hammer home the message, telling them that “strong oversight is how we're going to deliver for the American people on time and on budget” and make sure investments “get to where they're supposed to go.”

Sean Moulton, a senior policy analyst at the Project on Government Oversight, told Spectrum News it’s a positive move.

“The Biden administration seems to be, you know, welcoming them in a little earlier, which is good,” he said. “They're bringing them in at a program design rather than, you know, really kind of investigating money after it went out the door.”

Part of that strategy goes back to Biden’s own experience overseeing the Recovery Act of 2009, Miller of the OMB said. That legislation included an oversight board with 11 inspectors general, with the lead watchdog over that money reporting “less than 1%” in fraud losses.

But some Republicans on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee want more centralized oversight.

Rep. Rodney Davis, ranking member on the Highways and Transit Subcommittee, introduced legislation with Rep. Peter Meijer to create a special inspector general specifically for the infrastructure law.

Davis said he would again push for the new IG if Republicans gain control of the House of Representatives in November, which could make him leader of the highways and transit subcommittee.

“We're going to utilize our oversight responsibilities in the majority to actually hold the administration accountable. We'll be calling in all of those individual IGs. I'd certainly like to call in a special IG that's there just for infrastructure spending,” he said in an interview with Spectrum News. “We need to be sure that these dollars are actually going to be spent as intended.”

One lingering concern, Moulton says, is the way that spending is reported back to federal agencies after it’s awarded to states, when it is often broken down into smaller local-level awards and individual projects.

The OMB has directed agencies to gather data project by project, Miller said.

”That goes much farther than what is required under the law,” he added. “We want to know, at a project level, precisely where the dollars are being spent, how the dollars are being spent and what phase the project is in.”

Moulton said that requirement has potential, but he is concerned about a lack of standardized, detailed reporting instructions for agencies so that the spending data collected is “apples to apples.”

“At the national level, it often gets lost. WWe don't see what the states do with that money. We don't see that sub-award out to a port project,” he said. “Whoever's overseeing that, we don't see who they're hiring. And so, you know, we get this incomplete picture.”

Part of that incomplete picture could be whether or not that the money is spent equitably, Moulton noted, a core priority for the Biden administration. Equity “expertise” is another thing that OMB has tapped federal agencies to employ.

Asked about project reporting requirements, a spokesperson for OMB told Spectrum News they plan to work with agencies to “implement program-specific approaches” to collect spending data, aiming for consistency “while still accounting for the wide range of projects” under the infrastructure law.