Nearly half of suspects in hate crime arrests this year had already been designated as emotionally disturbed by police, according to testimony given during a City Council hearing on efforts to investigate and prevent hate crimes.

In testimony, representatives from the NYPD’s Hate Crimes Task Force admitted to shortcomings in addressing the significant role that mental illness plays in hate crimes, saying that the unit does not track whether mentally ill arrestees receive treatment and that the unit should improve its coordination with mental health professionals.

The oversight hearing came amid rising bias incidents in the city: Hate crimes are up by more than a quarter since the start of the year when compared with the same period in 2021, and up 100% for that period since 2020, according to the latest NYPD citywide tallies.

Year to date, hate crimes against Jews are up 72%, to 95; hate crimes against gay men are up 100%, to 20; hate crimes against Black residents are up 100%, to 24; and anti-Asian hate crimes are down 62%, to 25, Andrew Arias, the head of the NYPD’s Hate Crimes Task Force, said at the hearing.

Police officials said there have been 100 arrests this year related to hate crimes; 47 of those people had already been involved in an incident that led to police deeming them an "Emotionally Disturbed Person," police officials said.

When asked to explain what was causing the ongoing spike, government officials at the hearing did not mention mental illness, but pointed to some people’s racist associations of Asian people with COVID-19, the news media and increased reporting of hate incidents as drivers of hate crime numbers.

“The underpinnings of what actually causes this uptick is something that I don't know we've been able to pinpoint one direct correlation,” said Deanna Logan, the head of the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice.

In response to questioning from Council Member Nantasha Williams, the chair of the council’s human rights committee, Logan suggested that it was impossible to know whether the rising number of reported hate crimes was a bad thing.

“In a very ironic way, the fact that people are comfortable to come forward and tell about the horrible incidents that are happening to them, may be part of the work that you see,” Logan said. “I’m not quite sure that, in this moment, that seeing an increase in reporting is a criteria that we should take as negative.”

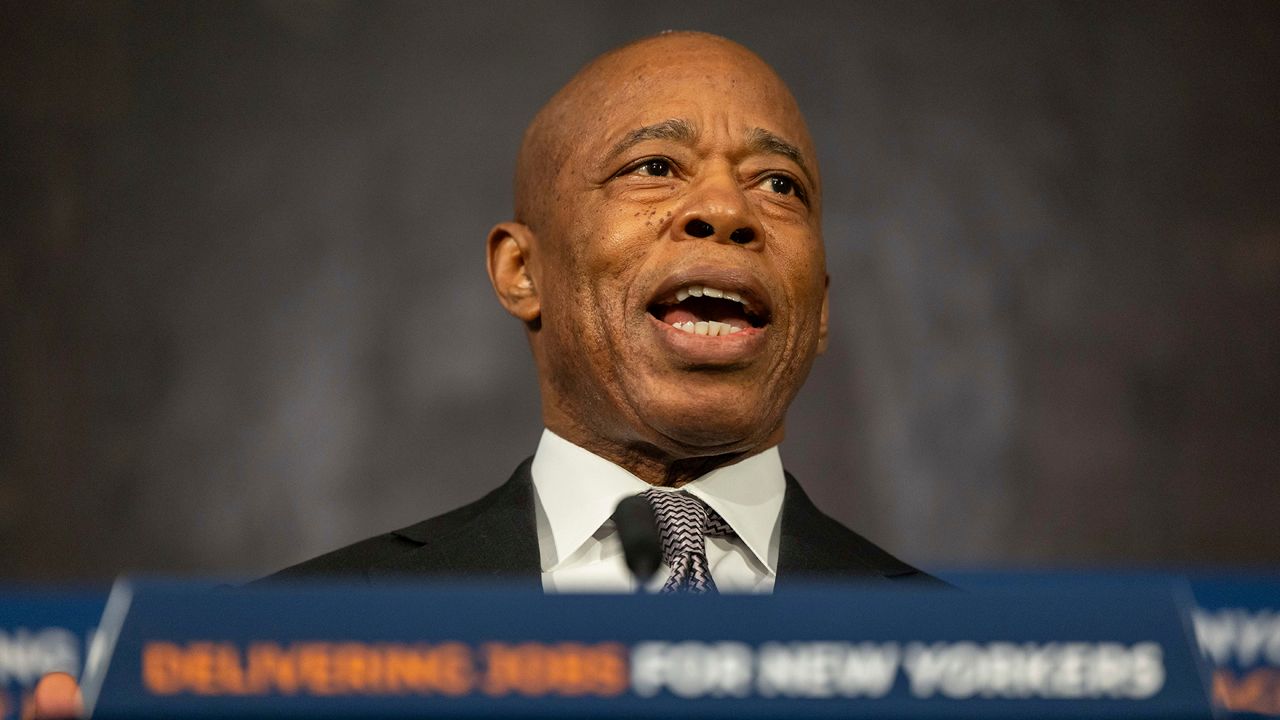

In Mayor Eric Adams’ recently released executive budget plans, personnel funding for the hate crimes section in the administration’s criminal justice office remains flat from the previous fiscal year, at about $500,000.

Arias, who has led the Hate Crimes Task Force since February, responded to council members’ concerns about reports of lax investigating of hate crimes by the NYPD.

The previous head of the task force, Jessica Corey, was reassigned after a Chinese woman who reported being verbally assaulted on a subway train said that Corey suggested she had “triggered” the assailant by filming him.

Arias acknowledged that “certain cases may never make it to us” because of poor reporting or labeling of criminal incidents as hate crimes by any of the three levels of NYPD personnel, including officers, lieutenants and captains, that review those incidents before they are referred to the Hate Crimes Task Force.

Arias added he wanted to make training for police officers around identifying and reporting possible hate incidents more “robust,” such as by including representatives from nonprofits, such as the Anti-Defamation League and the Asian American Federation.

“We want to know about possible incidents, because it’s our mandate to investigate them,” Arias said. “Nobody in this city should have to face violence or vitriolic speech or any of the like when going about their business.”

The task force does not collect data on whether mentally ill people arrested for hate crimes receive court-mandated treatment as part of their arraignment or sentencing, Arias said. He suggested his task force should “improve in our partnership with mental health professionals” to address the high rate of bias incidents committed by people experiencing mental health crises.

The Mayor’s Office for Criminal Justice pointed to its programs that provide grants to community organizations, generate school curricula for discussing hate incidents and “days of visibility” to raise awareness of such incidents in neighborhoods where they occur as pillars of their efforts to prevent hate crimes.

But the city representatives indicated they had little ability to determine if their efforts work to actually reduce hate crimes.

Michael Clark, the head of legislative affairs for the NYPD, said at the hearing that the number of hate crimes committed so far this year — 200 in total — was not large enough to analyze for whether increasing police levels in areas that see spikes in hate crimes effectively lowers the rate of new bias incidents.

“It’s a big number, but it's not so big that trends are easy to identify in that way,” he said.

Several council members expressed their concern over the lack of hard results from the city’s efforts.

“I really can't see any evidence that these strategies have had any impact,” Williams said.

_Dnt_MTA_Fare_Gates_Clean)