In 2005, scientists working for ExxonMobil began sampling gases leaking from the soil around their old oil refinery, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

The testing came decades after the discovery of one of the largest oil spills in U.S. history: Exxon had let more than 17 million gallons of petroleum products leak into surrounding soil and water, including the nearby Newtown Creek, which divides Queens and Brooklyn, according to a state lawsuit against the company. A Coast Guard crew discovered the spill in 1978, during a routine flyover of the creek.

Newtown Creek eventually became New York City’s largest Superfund site.

Yet tests by Exxon and the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation ended up finding significant pollution from three unrelated industries around Greenpoint’s Meeker Avenue: highly toxic chlorinated volatile organic compounds, which government scientists determined had been dumped by dry cleaners, metalwork foundries and a lacquer factory in the area.

Last month, the area around Meeker Avenue became the city’s newest Superfund site.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program lists more than 1,300 places across the country that require intensive cleanup due to man-made chemical pollution. The program, which has 85 sites in New York State (the fourth highest state total), passed Congress in 1980 with the goal of charging the companies responsible for chemical dumping with the cost of the remediation. If a company can’t pay, or no longer exists, the EPA pays out of a historically limited fund.

When a site is added to the EPA’s list, it gets put on a journey toward cleanup — albeit sometimes a long one. New federal funding for the Superfund program, however, added under the Biden administration, will likely lead to faster turnarounds.

The city’s Superfund sites are in various stages of cleanup and have seen different levels of attention from the city, from the infamous Gowanus to a little-known block in Queens. The official designation for the sites has in most cases come after significant advocacy from community groups, experts say, showing the importance of community activism.

“I think we need to understand how much of our country is contaminated, and these sites — not all of them are going to be cleaned up,” said Andrea Parker, the executive director of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy. “So I feel very lucky that we got Superfund designation here.”

Here’s what you need to know, on Earth Day 2022, about New York City’s Superfund sites.

The newest site: Meet the Meeker Avenue plume

It’s not a coincidence that the city’s latest Superfund site is on the banks of Newtown Creek.

“Greenpoint was the gateway into the industrial revolution for Brooklyn,” Lincoln Restler, the city councilman for the 33rd district, which includes the neighborhood, said.

After decades of industrial work, the neighborhood has now become largely residential. Now, leftover chemicals dumped and spilled by long-gone factories — the DEC has named Klink Cosmo Cleaners, ACME Steel and Lombardy Street Soap and Lacquer Mfg. among the responsible parties — pose serious risks to residents’ health. The EPA hasn’t yet determined if there are any “potentially responsible parties” it can charge for cleanup.

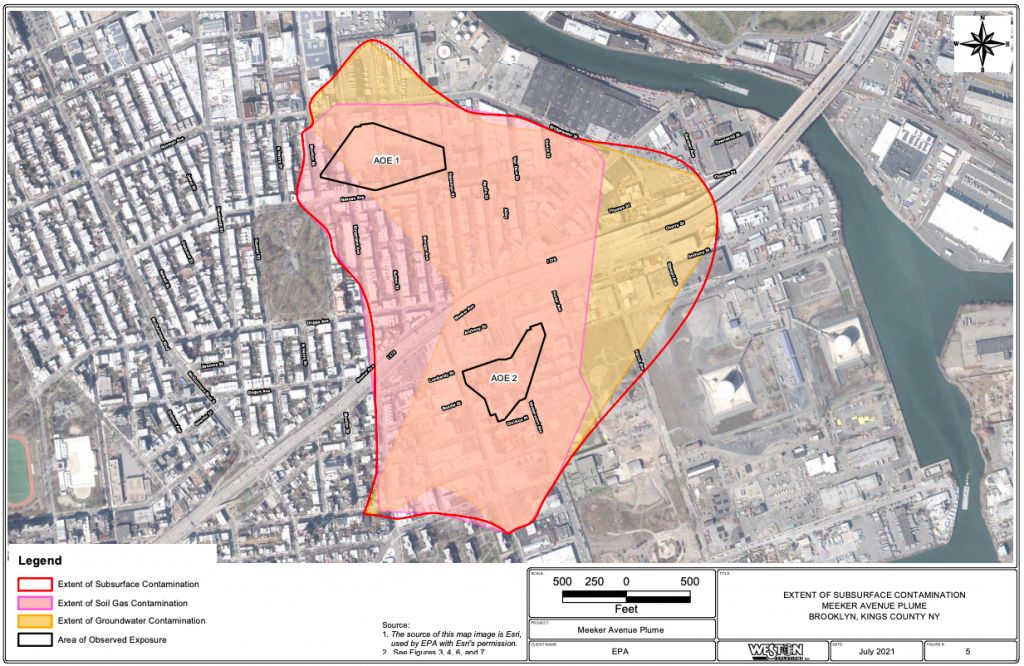

In March, the EPA added the Meeker Avenue area — a roughly 45 block parcel in the southeastern part of the neighborhood, and divided by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway — to its list of Superfund cleanup priorities. Now, the agency is preparing to start a preliminary study of the site, the first step to determining how, and how long it will take, to clean up the chemicals.

In the meantime, the risk to residents is unclear. The chlorinated solvent chemicals in the soil cause vapors that can seep into basements (hence “plume”); the DEC said it has installed 24 systems under homes and businesses in the area to dissipate the vapors.

“It’s been confusing, and hazy,” Restler said. “Exactly where those plumes were migrating, and who was at risk, has never really been clear.

Because the site has been under investigation by the DEC since 2007, there is a “baseline of data,” said Willis Elkins, the executive director of the Newtown Creek Alliance, meaning cleanup could happen relatively quickly.

Stephen McBay, a spokesperson for the EPA, said its upcoming feasibility study will determine whether they can use certain technologies to address the contamination.

“At this moment, it’s too early to decide what cleanup options are available or unavailable to us and how they might impact businesses or residences,” McBay said.

The others: Gowanus, Newtown Creek and more

Gowanus Canal, Brooklyn

Perhaps the city’s best-known Superfund site, the Gowanus received its designation in 2010; dredging of the canal’s sludge-filled bottom began in a pilot program in 2017, and continues apace now.

That work has resulted in significant progress, according to Owen Foote, the treasurer of the Gowanus Dredgers, a group that organizes cleanups and canoe outings on the canal. Now, as opposed to before, a low tide in the canal doesn’t expose its tarry bed.

“We’ve got images inside our boathouse of just how bad it used to be,” he said. “Not being able to see bottom at low tide, it means they’ve done a lot of removal.”

The work, however, has created some secondary issues, said Parker, the director of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy. Construction along and in the canal means that bridges over it are often closed, congesting local streets. Trees along the canal’s shore and mussel habitats in its waters were relocated by crews with excavators.

The city also recently rezoned the area, foretelling an influx of new residents, and potentially pushing out creative workers who have studios and galleries in the area.

Parker said that it is incumbent on the city to continue listening to residents as the remediation work continues, and is eventually completed, to make sure that the city doesn’t fully erase the “habitat and culture that was built into the contamination.”

Newtown Creek, Queens and Brooklyn

Four miles long, with 11 miles of shoreline, Newtown Creek is considered one of the most contaminated waterways in the country. It is ringed by factories, and saw significant chemical dumping over the last century; scientists are still figuring out whether chemicals are still actively leaching into the water, according to Elkins.

Newtown Creek got on the Superfund list at the same time as the Gowanus, but has followed a different path. The EPA has not released a plan for cleaning up the waterway, which could involve extensive dredging, despite completing a series of reports on the extent of pollution in the creek, its remaining ecological habitat and health risk assessments. McBay said the agency will release a plan no sooner than 2024.

The agency has named several companies responsible for polluting the site — including Exxon Mobil, BP, Chevron (which owns Texaco, the company that had a facility on the creek) and New York City itself — paving the way for cleanup funding.

“It’s still up in the air,” Elkins said. “We don’t know what the remediation is gonna look like.”

The agency has given a range of between 2030 and 2035 for a completion date, but Elkins said that he and local environmental groups would like the cleanup to take as long as it needs.

“We know the impacts of a lesser remediation or a delayed remediation are gonna be,” he said. “It’s what we’re facing right now: It's a toxic waterway that's not safe to fully interact with.”

Wolff-Alport Chemical Company, Queens

In 2014, the EPA added a triangular block of Ridgewood, Queens, to its Superfund list: the former site of the Alport-Wolff Chemical Company. Alport-Wolff, which operated from the early 1920s until 1954, imported monazite sand, a mineral compound, from the Congo region of Africa and extracted rare earth elements from it.

Monazite sand, however, contains thorium, a radioactive element. Until 1947, according to the EPA, Wolff-Alport disposed of the thorium waste into the sewer and “possibly by burying the waste on its property.” It wasn’t until 1988, however, that a study by the EPA and the city’s health department confirmed radioactivity at the site.

The EPA has installed shielding in layers of concrete, lead and steel to businesses on the site and under the sidewalk along Irving Avenue. Yet all tenants on the block, which sits across the railroad tracks from Trinity Cemetery and next door to the popular club Nowadays, will eventually have to leave: The EPA’s plan calls for demolishing all the existing buildings, removing contaminated soil and cleaning the entire area with high-pressure water jets.

Federal funding for Superfund projects included in the infrastructure bill passed last year, totaling $3.5 billion over the next several years, will likely speed the Wolff-Alport remediation along faster than it might have gone in the past, said John Prince, the deputy director for the EPA’s Region 2, which includes New York.

That’s because the EPA determined there was no one to pay for cleanup; the Wolff-Alport company no longer exists. With the new funding, however, the agency is greenlighting construction at dozens of stalled cleanup projects, and pushing forward studies and work at so-called “orphan” sites that don’t have a private company paying for the work.

“We’ve had to do that triaging of sites for decades,” Prince said. “All of a sudden we're like, ‘nope, if you're ready to do the work, we should be able to fund it.' That should be the case for the next three or four years.”

Hudson River

The Hudson River is not an active Superfund cleanup site, and New York City was not part of the central cleanup area, but its history with dumping of plastics chemicals means that the EPA conducts reviews every five years of its remediation efforts. The Superfund designation came more than 20 years ago, when the ordered the dredging of 2.65 million cubic yards of sediment on a 40-mile stretch of the river, from Troy north to Fort Edward.

The agency is now starting its third five-year review, based on data collected on fish, water and sediment between 2017 and 2021. A previous review did not determine whether the dredging, and capping, of the river had a significant effect on fish health, because of a lack of fish tissues collected. The new review should be released this fall. It won’t be the last: The EPA has said it plans to monitor the river’s health for several more decades.

What are the health effects of Superfund sites in the city?

Superfund sites are associated with a wide range of chronic health issues and diseases, according to Dr. Ana Navas-Acien, the director of Columbia University’s Superfund Research Program.

“These chemicals have multiple health effects, induce systemic toxicity,” she said, leading in some cases to cardiovascular problems, neurological effects, cancers and kidney diseases.

Yet in a place like New York City, determining whether a health problem is related to a specific Superfund site can be exceedingly difficult, because of overlapping sources of pollution and poor health. A nearby highway — like the BQE bisecting the Meeker Avenue Plume site — as well as the city’s history of chemicals in heating oil and poor health care access in some areas can cause or compound many of the same health issues found by Superfund sites.

“There's so many layers of complexity,” Navas-Acien said.

At some sites, health risks can be relatively low, according to government assessments. At Wolff-Alport, where radioactivity has been an issue for decades, the exposure level is less than what is allowed for workers in nuclear power plants.

Elkins, of the Newtown Creek Alliance, said that the city should take health risks from Superfund sites seriously even outside of residential areas.

“Just because something is zoned as industrial and used by industry doesn't mean it shouldn't get a high level of cleanup,” Elkins said. “There are people working here, 40, 50 hours every single week, who are having exposures to the water, the air and the soil, and they need protections afforded to them.”

Will the city get more Superfund sites in the future?

Navas-Acien believes the city likely needs more sites than it currently has, to address issues like lead contamination of soil that are more directly linked to certain health effects, she said.

“That lead, it’s very likely coming from an industrial origin,” she said. “It’s not lead paint, it's not lead from gasoline.”

Restler, the council member representing Greenpoint, said Meeker Avenue needed the designation because he felt that the state DEC didn’t have the resources or the legal power to fully clean the site.

“I am heavily relieved that we finally have a partner in the EPA that has the resources at its disposal to clean this thing up,” he said.

The DEC runs its own Superfund program, with thousands of locations across the state. The agency’s environmental cleanup programs received $120 million in the recently passed 2023 state budget, which the agency said did not include enhancements for the Superfund program. Its Brownfields Cleanup Program, which provides tax incentives for remediation projects, was extended for another 10 years in the budget.

“New York State’s Superfund program is a highly effective tool in developing and implementing comprehensive plans that address contamination to ensure the protection of public health and the environment,” Lori Severino, a DEC spokesperson, said in an emailed statement.

How to get involved in Superfunds

One way to try and get more Superfund sites in New York City is to demand them; that’s how Greenpoint residents got the Meeker Avenue site designation, Restler said.

“We are experienced and organized at fighting back against corporate entities and others that have polluted our neighborhood,” he said. “I always would encourage neighbors across the city to identify the environmental justice groups around them, and push city, state and federal officials to do their jobs.”

In Greenpoint, Restler said, the Newtown Creek Alliance and North Brooklyn Neighbors were “instrumental” in getting the Superfund status.

Residents can also join the community advisory groups that the EPA convenes for each Superfund sites. The groups monitor the progress of the cleanup, and can serve as a conduit for information between the EPA, elected officials and the broader community. You can go to this page to learn more about Superfund community advisory groups and contact an EPA Region 2 representative about joining one.

Navas-Acien said that residents can also look to environmental justice groups like WeAct and South Bronx Unite to learn how to bring awareness to local pollution issues and access to green space.

She also encouraged residents who are concerned about pollution in their neighborhoods to reach out directly to scientists working in the city, including in her program.

“The days where scientists would do their work alone are gone,” she said. “We really need to listen to the citizens and understand what the issues are.”