Depending on your perspective, the highly contentious 2020 presidential election might feel like it was ages ago, or might be fresh in your memory like it just happened.

Well, believe it or not, the 2022 midterm elections are just months away, and with control of Congress – and, invariably, the second half of President Joe Biden's first term – at stake, this mid-cycle election is just as important as a presidential contest, and possibly even more so.

The race has technically already begun: Early voting is already underway in Texas, which is holding first primary of the year.

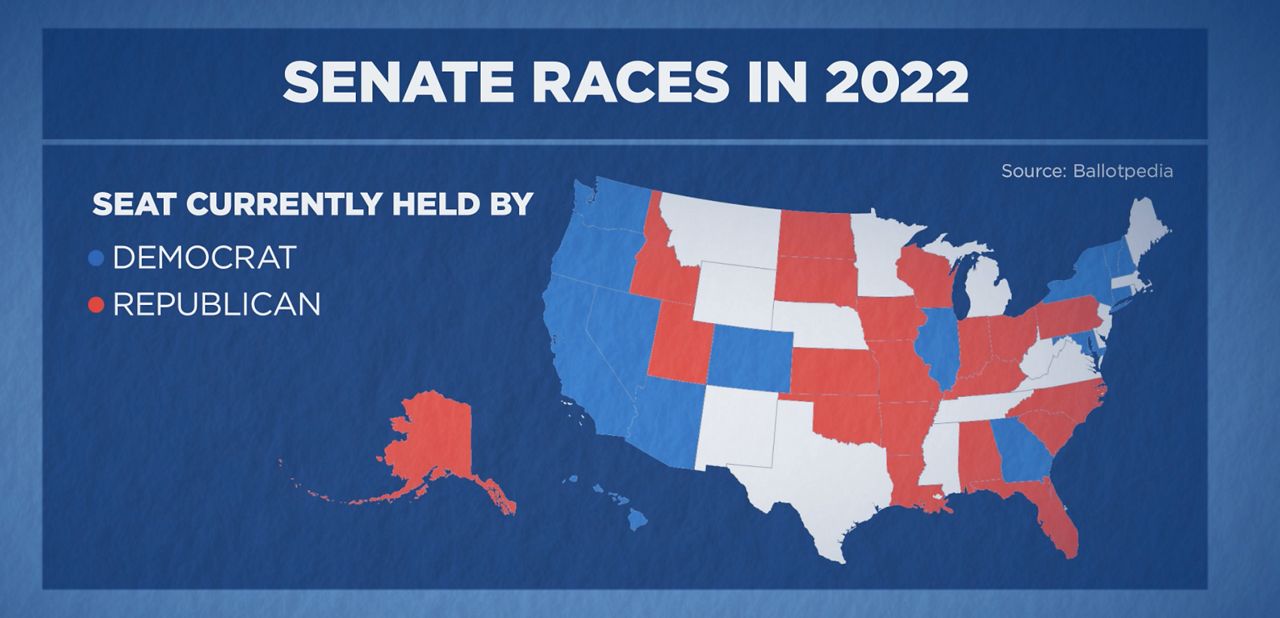

Thirty-four of the 100 seats in the United States Senate – roughly a third – are up for grabs in November. So are all 435 seats in the House of Representatives.

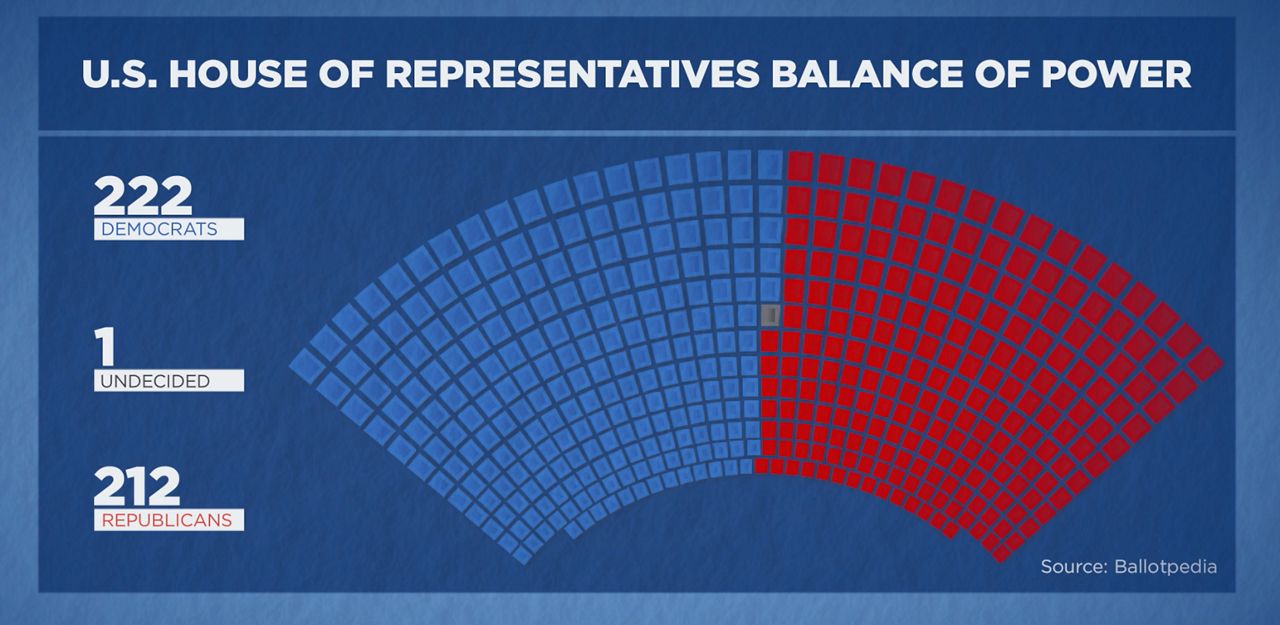

In the House, Democrats hold a 222-212 advantage over Republicans, with one seat open after California Republican Devin Nunes' abrupt resignation at the beginning of this year.

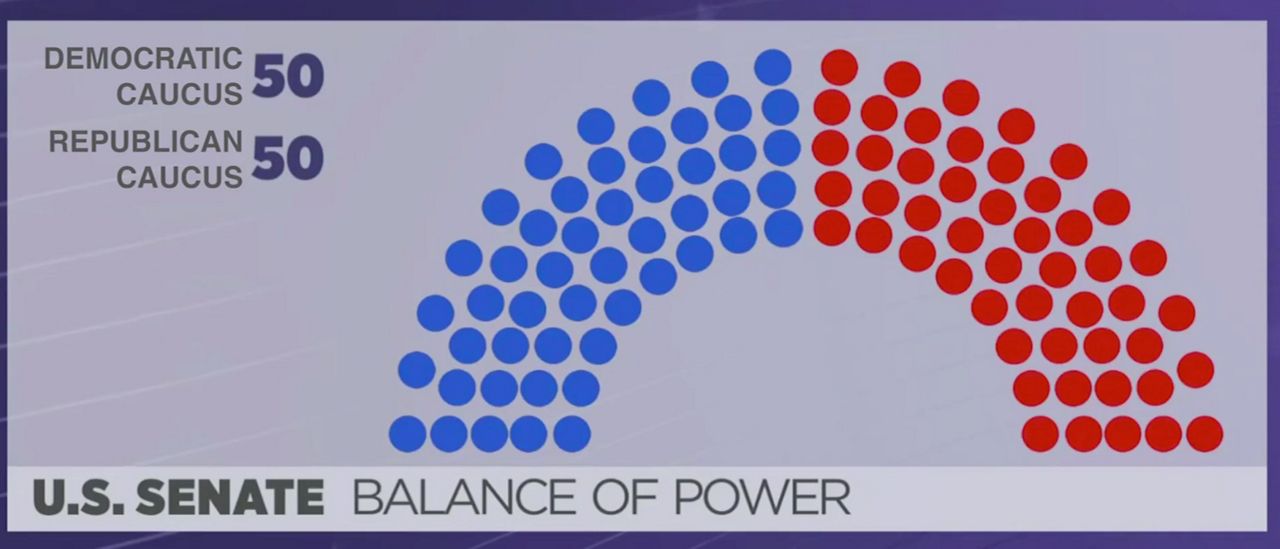

The Senate is evenly divided – 50-50 – because Vice President Kamala Harris is a Democrat, and can break 50-50 ties, her party has the edge.

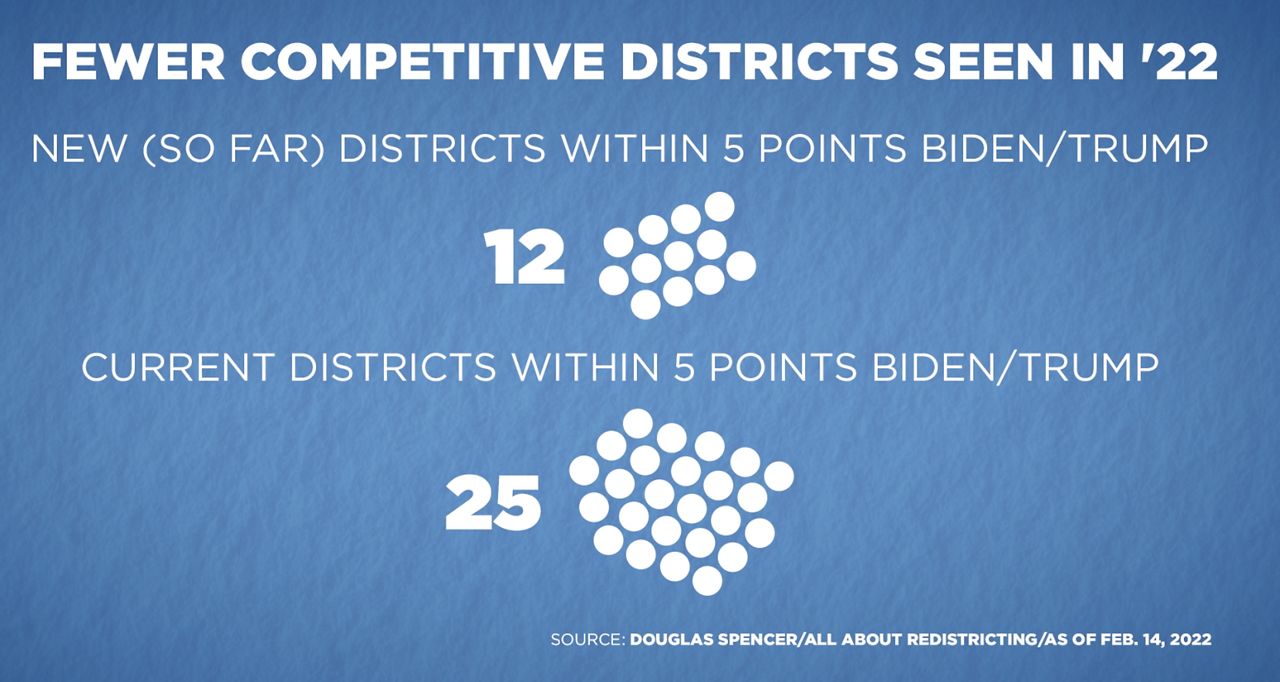

In states with more than one House member, the congressional districts are redrawn every 10 years, based on the Census. The most recent redistricting is concluding, and one trend is clear: Most of the districts created so far favor either the Republicans or the Democrats. Relatively few districts will see truly competitive elections in November.

There are only 12 districts approved so far that Joe Biden or Donald Trump won in 2020 by less than 5 percentage points. But a decade ago, there were 25 such competitive districts.

“Both parties seemed pretty satisfied to take safer seats as long as they knew they would control them for a lot – for several elections going forward,” said Doug Spencer, an associate professor of law at the University of Colorado, who runs the website All About Redistricting.

Of course, it’s not over until the voting is done. As of now, Republicans are seen having the advantage. Parties out of power in the White House overwhelmingly tend to pick up midterm seats. And President Joe Biden is now underwater in popularity.

“You have independent voters that don't like either party, and they tend to use these midterms to put a check on the president rather than giving them a blank check,” said Tom Davis, a former Republican Congressman from Virginia. “They're happy when not too much is going on.”

Republicans are also motivated - fielding far more federal candidates – 814 for the House of Representatives to 683 Democrats.

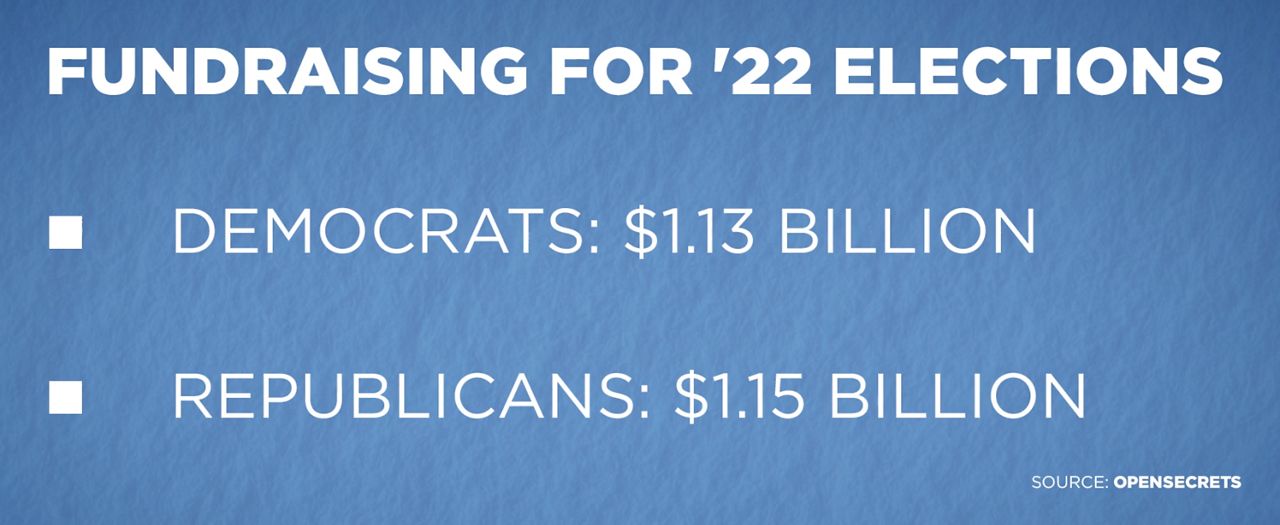

But the fundraising battle is pretty tight. Based on recent filings, it’s $1.13 billion for the Democrats, $1.15 billion for the Republicans.

Democrats’ are struggling with a singular message, but no shortage of ideas, like tapping into both economic security – and the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol.

“You have an opportunity right now to clearly differentiate the party, the Democratic Party as the Workers Party as opposed to the terrorist party,” said Nomiki Konst, a member of the DNC Unity Commission, which began in 2017 and was tasked with reforming the Democratic Party.

There’s another variable: Former President Donald Trump is taking a very active role in G-O-P primaries – backing candidates who support his false claim that he won in 20-20.

Some Republicans think he’s good for turning out voters. Others counter that Trump makes it easier for the Democrats to re-run their successful 2020 playbook.

“The irony here is I don't think he really cares that much about the party,” Davis said. His team seems to be centered on himself, which is not a bad trait for a politician. But it's not good for a midterm election and party building.”

How should Democrats handle him? Some say concentrate only on the economy; others believe the party should seize on the Republican National Committee’s recent declaration that the storming of Congress on January 6th last year was “legitimate political discourse.”

“That doesn't mean that all Republicans support these terrorist attacks,” Konst said. But the Republican Party has made a choice to basically blanket the politics of the terrorists on Jan. 6th, with all the other Republicans who vote on the Republican Line for lots of reasons”

A number of Republicans, including Minority leader Mitch McConnell, have criticized the RNC and called January 6th an insurrection.

Were Republicans to take power, at least in the House, the Jan. 6 commission would likely be shuttered, or refocused on security lapses under the watch of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Republicans say they would also turn to investigating Democrats, and the President’s son, Hunter.

Hunter Biden has denied any wrongdoing.

President Biden already is having trouble getting his agenda through Congress. Should Republicans gain control of The House or Senate there would likely be no movement on what he’s called for – like universal preschool, increased voting protection and clean energy incentives.

“Dead, dead, dead,” Spencer said. “I don't see any appetite to take any action on any of those issues.”

If Republicans take the Senate, they could also block nominations – including, potentially, another Supreme Court vacancy. While President Biden's pick to replace retiring Justice Stephen Breyer is likely to sail through the Senate in 2022, what might happen if Republicans retake the Senate becomes murkier.

In an interview last year, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said that should Republicans take control of the Senate in November, it would be “highly unlikely” that a Supreme Court nominee picked by President Biden would be confirmed in 2024.

“I think in the middle of a presidential election, if you have a Senate of the opposite party of the president, you have to go back to the 1880s to find the last time a vacancy was filled,” McConnell said. “So I think it’s highly unlikely. In fact, no, I don’t think either party if it controlled, if it were different from the president, would confirm a Supreme Court nominee in the middle of an election.”

McConnell’s comments hearkened back to his actions in 2016, when the then-Majority Leader blocked Merrick Garland’s nomination by then-President Barack Obama to fill the vacancy on the high court left by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.

“The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice,” McConnell said in February of 2016, shortly after Scalia’s death. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.”

Garland’s nomination expired on Jan. 3, 2017, months after Republican Donald Trump won the presidency. Trump nominated Justice Neil Gorsuch to fill the role, his first of three justices he appointed to the Supreme Court — more than any president since Ronald Reagan.

McConnell would later call blocking Garland’s nomination one of his “proudest moments.”

"One of my proudest moments was when I looked Barack Obama in the eye, and I said, 'Mr. President, you will not fill the Supreme Court vacancy,” McConnell said in a speech at an August 2016 event in his home state of Kentucky.

In the interview, the Kentucky Republican said Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation to replace the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was "different" because "we were of the same party as the president."

Barrett was nominated 35 days before the 2020 presidential election, the shortest period of time between a Supreme Court nomination and a presidential election in U.S. history — and was confirmed just days before the presidential contest.

The host went on to ask what McConnell would do if a justice stepped down in 2023, over a year before the election, and Biden sent a nominee to a hypothetically Republican-controlled Senate — citing the precedent of Anthony Kennedy, who was nominated by Reagan in 1987, but confirmed by a Democratic Senate.

“Well, we’d have to wait and see what happens,” McConnell said.

Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley, a Democrat, blasted McConnell on Twitter for his remarks.

"Of course Mitch McConnell will try to steal another Supreme Court seat if he has the chance," Merkley wrote. "We must fight with everything we've got to expand our Senate majority in 2022."